Identity Crisis: Tribal Nonenrollment & Its Consequences for Children

The Conversation: A growing number of children across the U.S. and Canada born to Indigenous parents are not being enrolled as “tribal members” because they are not eligible under blood quantum requirements, generally defined as the share of their ancestors documented as full-blood Natives. Lacking the documentation of their membership in a state or federally recognized Indian tribe, this generation of “Paperless Indians” are also not eligible for a wide range of tribal government services – from health care, housing, and jobs to hunting and fishing rights, religious protections and much more. Widespread non-enrollment of Indigenous children contributes to a widespread identity crisis among native youth, among whom suicide is the leading cause of death, and raises the question of whether independent, sovereign Indigenous nations will survive into the next seven generations or be completely dissolved and assimilated into American society.

Thanks to Souta Calling Last and Tyler Walls of Indigenous Vision for joining the EmbraceRace community for this conversation. In addition to watching the video and reading the lightly edited (for understanding) transcript, you should also checkout their tip sheet - Building inclusive communities and strong Indigenous youth - which outlines steps you can take to support Indigenous youth and tribes today.

EmbraceRace: Today's conversation is called Identity Crisis: Tribal Non-enrollment and its Consequences for Children. We are distinguishing between separate but related issues, between non-enrollment and disenrollment. Disenrollment is when a tribal member is stripped of his, her, their membership in the tribe. Non-enrollment is about what constitutes membership in the first place and who is not allowed to be a member.

And in terms of the sheer numbers of people potentially affected, nonenrollment is an even larger issue than disenrollment and it clearly affects children, Native children, who might otherwise be members of these tribes. So that's a conversation we're getting into.

We're really glad to have Souta Calling Last and Tyler Walls of Indigenous Vision here to key us in on the importance of this issue for kids and for tribes. Welcome.

Souta Calling Last: Thank you!

Tyler Walls: Glad to be here.

EmbraceRace: First, can you tell us a little about Indigenous Vision? Broadly, your work is to “revitalize Indigenous Communities – Land, People, and Culture – by providing educational resources through quality programs that promote well-being.”

Souta Calling Last: Yes. We have a few different programs. (Get the full list at indigenousvision.org.)

We have an emergency water systems project [there is no shortage of water issues in First Nation and Native American communities] raising money for emergency water systems for people who have compromised immune systems or are in a state of emergency of some kind.

We have youth empowerment programs. We just finished our Living Indigenous, Fostering Empowerment (LIFE) Spa which is for Indigenous girls who may or may not be in the foster care system but who are removed from home or from their culture.

Indigenous Vision's 2019 LIFE Spa (Living Indigenous, Fostering Empowerment), serving Indigenous girls who are removed from home (often in foster care) or from their culture.

Souta Calling Last: Yes. So this is the group picture from our 2019 LIFE Spa held at Flathead Lake and the women you see who are my age are all aunties and the lady in the middle there is Betty Cooper. She was our grandmother for the camp and she is also the Mother of the Iinnii, which is Buffalo, and Montana Mother of the Year. So we had some pretty high caliber people on our staff this year.

The girls are from tribes all across Montana, all seven nations in Montana- Lakota, Dakota, Assiniboine and I think that's it. So it was all seven nations in Montana and some Lakota girls as well. The camp is to reconnect the girls with the community and do it in a culturally relevant way – more on why we do that in a minute.

We have a Missing & Murdered Indigenous Warriors project which is a response to the missing & murdered Indigenous people epidemic. With that we teach girls around the country self-defense moves and situational awareness and how to take your protection into your own hands.

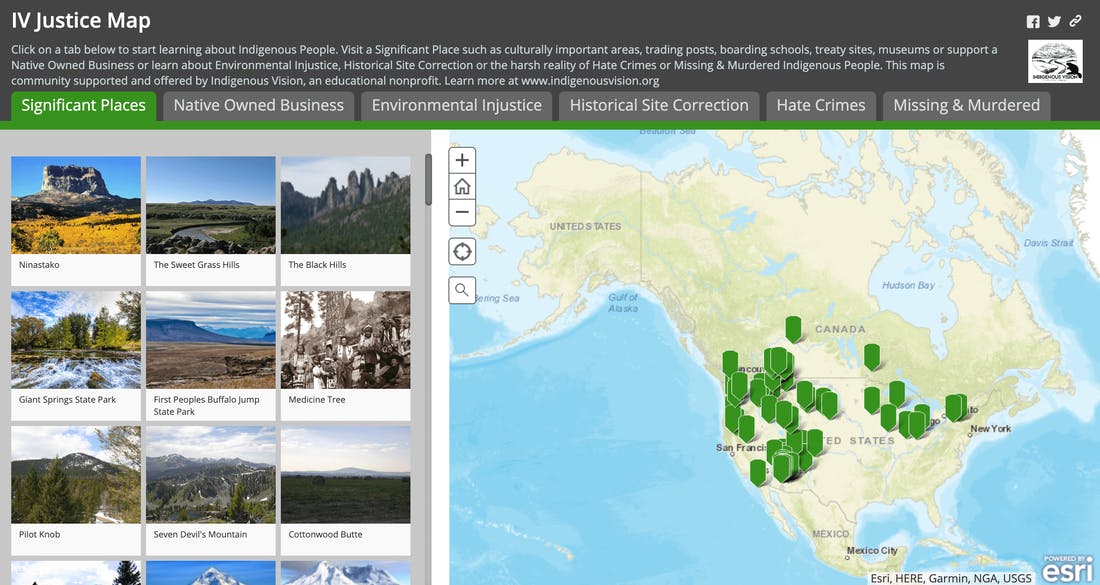

We are also building an Indigenous Vision (IV) Justice Map, working directly with Tribal Cultural Museums and community members to provide an accurate Indigenous perspective on historical and current events that are impacting our communities.

So right now it's almost a guarantee that the majority of what people learn about Native people is not from our perspective and it's not told by us.

Dehumanizing stereotypes, erasure and other misinformation about Indigenous people is ubiquitous on monuments and historical markers throughout the Americas.

Souta Calling Last: Even though this placard was erected in 1929, it's not really different from those that are put up you know five years ago and a year ago. There's still an ongoing narrative written about us that continues to dehumanize and perpetuates stereotypes of Indigenous people. The IV Map is an effort to have news and information about us by us.

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Souta. As you say, the work you do clearly does relate to tonight’s topic of how nonenrollment is affecting Native kids and tribes. We'll talk about exactly what are the rules of membership right or how the rules of membership in tribes is determined. We know that there are different from tribe to tribe.

But first, I wonder if you could give our audience a sense of what's at stake here? And I know that the stakes are very personal for you, for the two of you and your family – Souta and Tyler are a couple and have a child together. So what's at stake for your family in this question of non-enrollment?

Tyler Walls: Yes. So the whole existence of tribal people, sovereign nations is at stake. I come at it from a personal experience, both of us being tribal members. I'm a Hopi tribal member. Souta is a member of the Blood Nation and our child is not enrolled in any of our nations due to not meeting certain requirements for eligibility according to membership laws of each tribe, particularly our tribes, the Hopi Tribe, the Onondaga Nation, the Blackfeet and the Blood tribe. So what's at stake for my child, I’ll start with him as as an example.

The basic right of Indian status is the protection under certain laws and treaties. And so coming from a treaty nation, like the Onondaga Nation, we have in our treaties of 1794 and 1784, we had protected rights such as hunting, fishing, gathering, religious protections, to be able to pray and fast where we traditionally have been for thousands of years. Access to health care, access to social services or access to any of the services that the tribes may offer to tribal members. None of those are available to our child. There is an entire generation of kids that aren't eligible. And it’s a growing issue as we continue to marry outside of our Tribal Nations.

Souta Calling Last: And what's at stake in the bigger picture is the survival and the existence of tribes at all. There are roughly 80 tribes that have practiced disenrollment. But every single tribe will or is practicing non-enrollment of future generations of children or existing youth. So the very existence of the tribal nation as a people is at stake.

For me, the chord that strikes is that a whole heck of a lot of people died in the settling of this country. Estimates were between 100 and 120 million people. And by the time the first census rolled around there were only 247,000 individuals from Native American tribes. That’s a very clear genocide, having over 100 million people and then having all of those people die from various mechanisms of outright warfare, hunting, bounty hunting, disease, contagious disease and then everything that followed.

And now today, what's at stake is that being a member of a tribe affirms your identity as an Indigenous person. And when you have your identity affirmed by your community and your family, you're a much more powerful, confident person in that you know your place in the world and you know your purpose. Without that, you get depression, anxiety, suicide. Native youth have the highest rates of suicide in the U.S. compared to any other [racialized groups] right now. Just yesterday one of the tribes in Montana declared a state of emergency because of the suicide epidemic happening amongst youth and adults.

Tyler Walls: And so looping it back to “identity crisis,” besides the benefits or so-called protections under Indian status that we receive as far as the treaty rights, the religious protections under the law, that the tax exempt plan that we have in reservation system, besides the political and economic issues that play out in our lives, the emotional identity issues is having significant emotional impact on our youth's identity and the outlook that they have about themselves.

A lot of that [low self-esteem] is a response to external [negative] stereotypes all around them. But when it comes from their own nation or from their own people saying that you are not a tribal member because of, let's say, your blood quantum or because of whether you're descended from the tribe in question from you're mother's side and not your father's [in patrilineal tribes] or the other way around [in matrilineal tribes].

For example, we have nieces and nephews where one of the sisters is enrolled and the other sister is not enrolled. They're sisters. And yet we have a family made up of half of the kids being enrolled and then the other half are not enrolled. And so it plays on the issue of, where do they fit?

EmbraceRace: You've mentioned blood quantum. Right. My understanding is that really blood quantum had not been a criterion for membership in tribes 400 years ago. That it really was an imposition, at least in part, by the U.S. government which had its own strategic reasons for doing that. But I wonder if you could talk a bit more about blood quantum, how it factors into different tribes understanding of membership and also says something about whether or not and how these criteria for membership might be changing over time.

Souta Calling Last: So in 1934 is when the Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) here in the United States. And when the IRA passed, it was housed under the Bureau of Indian Affairs which was housed under the Department of War. So that sets a tone.

And at that time, they were ending the termination era and starting the assimilation period and the relocation programs. And then not too far after that was the “Sixties Scoop” in the 50's and 60’s (and in some areas into the 80s), when Native kids were taken from their families and sent out of the communities to foster care and residential schools in U.S. and Canada. Eventually those programs were shut down when they got public pressure for the way they were run and for the survival rate of Native youth in these facilities. And we thought the Sixties Scoop ended, but today we are finding that Native children make up more a disproportionate amount of kids in foster care.

I think what happened next was that they started to target our children in a different way. Right now in Manitoba, Native children make up 90 percent of the children in foster care even though they're around 2 percent of the entire population of the province. And so some of these mothers are delivering the child and by the time she can even recover or think straight, Child Protective Services is at the bedside saying she's not fit. So it's at the discretion of nurses and doctors and staff in the facilities, but there's a lot of discrimination and a lot of stereotypes that are happening in our institutions and facilities where babies are being born that are giving Protective Services the rights to take away our children in an unprecedented number. So the harm continues.

EmbraceRace: From what I understand you saying, Souta, is the Sixties Scoop as the official policy of the U.S. Government or the Canadian government is over. But in effect it continues today even though it's not formal policy.

Souta Calling Last: Right.

Tyler Walls: Blood quantum is a colonial concept that was forced upon us over the process of forceful assimilation into American society. I'm a numbers guy. I'm a math guy so I'm able to break down fractions. And last night I was breaking down my son's fractionization of who he is and there's nothing more dehumanizing.

So using Hopi as an example because I am an enrolled member of the Hopi, I am by blood quantum one quarter Hopi through my maternal grandfather. My mom's dad is my Hopi lineage that I'm able to claim through Hopi enrollment and they are one quarter. Because they're at one quarter, my son cannot become eligible therefore because I'm it, I'm the last generation as far as me and my siblings go. And that blood quantum was put into the Constitution, amended I believe in 1992.

Originally in the 1936 or 1939 original Hopi constitution, a blood quantum was inserted in the Constitution through the Indian Reorganization Act. It was a federal policy in 1934. A lot of our tribes organized, known as IRA tribes, under this act, and it was basically a boiler plate that the Bureau of Indian Affairs gave the tribes and said, "Here, fill out your constitution that's fitting to you. You can edit it as you wish." But blood quantum was part of the boiler plate used to create the Constitutions. Blood quantum also has history way back in the past. Obviously in the late 1700's we had people who were intermarrying with the early colonies. So it's noted in record that that occurred.

Fast forwarding to the late 1800's in the allotment period, I saw a lot of literature about blood quantum during land allotment. And so in order to pass on allotted land, for instance, you had to be one quarter Indian blood. And that was over one hundred years ago and so here we have generations removed from that and we're starting to see less and less Indian blood and so descendants aren't able to hold land. And so it involves the whole spectrum of identity, land, and everything.

EmbraceRace: So it’s sort of another form of termination.

Souta Calling Last: Yes.

Tyler Walls: Exactly.

Souta Calling Last: And so bringing that down to a personal note.

Smudging is burning a dry herb, usu. sage or sweetgrass and using hands to wave the smoke over body spiritually and energetically cleansing oneself, an object or space. This morning we were smudging sage in preparing for today's loaded conversation - it's such a heavy conversation and a lot of people feel very passionate about open enrollment or closed enrollment but ultimately at the end of the conversation, both parties want to preserve the tribe. And so we were smudging sage this morning and we smudge our son, and he's a really good smudger himself!

Anyway, I was thinking that my mom is really good at telling our family history. And from a really early age, I knew a lot about my grandmothers, a lot about my family history. We're descended on the Blackfeet side. We come from a family of hereditary chieftainship and my grandmothers have always picked sage in this particular area. And so this year, when we went back, we saw that in that area where we harvest our sage, was a sign that said, "All outdoor activities need permits. Permits are required." And so I thought of the obstacle that that put in front of me.

[NOTE: The Blackfoot Confederacy consists of 4 Nations, and Souta's parents are members of two of them, the Blackfeet and Blood. Souta can't be enrolled in two tribes at the same time. Her Blackfeet blood is not recognized.]

First, I go out to the land where my grandmothers have always gone for as far as I can remember back. And I start to pick sage but then I'm met with trauma and I'm almost retraumatized by seeing these signs out knowing that in my head, okay well this is the reservation I was raised on. This is my ancestral territory. I come from two Native nations that belong to this land. Yet in this country, because we were sister nations and the U.S. Canadian border divided us, there's all these obstacles I have to face about U.S. services for Native Americans. And if the organization I'm working with will honor that historically, my tribe has always been in Montana in this area and we didn't decide where the border goes or if they will honor that my tribal I.D. says Canadian and has a little maple leaf on it and then they therefore are like, "You are not a US citizen. You're not a Native American." Despite my relationship with the landscape.

And then the second fear that compounds that is that I at least have an argument, as a descendent, too, if I get caught, and the permitting process and the obstacles I would face of possibly having to go to court for that, but I'm also trying to teach my son the habit of smudging himself and praying and meditating in the mornings and making it a daily practice so he will have to know where to harvest and how to harvest that. But he [is even more removed than Souta who is not enrolled but has an enrolled parent]. He may or may not be honored and he definitely will not be enrolled in the tribe where his grandmothers and grandfathers are from. And so his obstacle of just trying to maintain his daily peace as a Native man is impacted then and that has a lot of implications of like okay well as a mother, any obstacles he faces in life right now, I'm supposed to teach him how to deal with that. And when things get too big you just have to give it to the Creator, they say. And so that directly impedes you know his religious freedom as a Native person or a Native descendant that may or may not be recognized.

EmbraceRace: A lot of people are facing this problem. How hard would it have been for you to marry within your tribe and not have this issue? No offense Tyler.

Souta Calling Last: *laughs*.

Tyler Walls: So it's a legitimate question.

Souta Calling Last: And it's kind of a joke too. Like you don't want to marry your cousin. *laughs* At a certain age or in my late 20's, I went home to my reservation, which was the Browning community, the Heart Butte community, and the Stand Off community of the Blood tribes. And I am lucky in that I have four tribes to choose from that are all Blackfoot nation. So they all speak the same language. They all practice the same culture. And I thought, "Should be easy, right? Like I should be able to find a man". *laughs* And it's funny to me that you know, I literally the age I was, went out looking for a husband because I wanted to have a family and I wanted to find the right person. But you know it's a very small dating pool and I come from the Aakaipokaiksi clan, which means "many children clan." So that gives you an idea of just how many people I'm related to!

And I have family members in every single one of the four nations of the Blackfoot Confederacy. I have my mom's Blackfeet family. My grandpa is Blood and we have family members in Brocket, which is the Piegans. And Siksika as well is where my grandma is from. So I'm related to every single one of the four nations in my Confederacy. And I just couldn't find somebody who was my age that I was attracted to that was like family ready. *laughs* And I tease Tyler all the time. I'm like, "Why couldn't you just find a good Onondaga girl?" *laughs*.

Tyler Walls: Well it's true. And I asked that same question to an Onondaga Chief when I was going through college in my early 20's. And this was in Arizona. And my peoples, they come from just south of Syracuse, New York. There's an Onondaga Nation reservation that we still hold on to. And he kind of chuckled at me and he's like, "Good luck finding an Onondaga woman." And you know, and as a young person, I'm like oh hey, is that kind of dead on arrival? Do I stop looking for an Onondaga or do I not care? Or do I now shift my my focus on Hopi women?

Souta Calling Last: *laughs*

Tyler Walls: You know, it's just so weird that we have to choose and really determine looking forward to our children if I don't marry into my tribe, they're gonna be less of a percentage or if I marry a non-tribal woman, my child is going to be even less Indian. My father's white and my mother's Native and so I'm right down the line 50/50. And that itself has had a tremendous effect on my identity building over the last decade, especially after high school and into my college years. And even now, I'm still coming to understand who I am. My history, my family. A lot of that was severed due to the number of federal policies that removed us from our communities, that plagued our communities, such as the domestic issues that we see. But but yeah it is so interesting.

So in Onondaga, we have one half blood quantum, is what the Chiefs of Councils told me. So I actually applied for Onondaga. And my mom is Onondaga. She also could have been enrolled in Hopi but we Onondaga, we are matrilineal descent. So meaning our lineage comes from our mom's mom's mom. So every grandmother before my mom was Onondaga for thousands since time immemorial and yet here I am. My mom is Onondaga. I come from that matrilineal line, but the tribe, the nation says that I'm not eligible because I'm not 50 percent Onondaga. That plays a role on my makeup of who I am.

EmbraceRace: And hopefully this is all clear to folks who are listening but I'm going to attempt a close analogy and you tell me if I have it right. So first of all, we're talking about sovereign nations which I think is a thing that perhaps a lot of non-Natives don't understand. We're talking about sovereign nations. So it would be as if I were European and I had parents and grandparents and you know going back forever and this is beyond dispute. They were Greek and Polish and English and Belgian and Swedish and all of these things but couldn't get citizenship in any of those. All right. Yes that's the problem we're talking about, where citizenship is not just a nice idea. It comes with specific benefits and also some sort of symbolic status. So is that a fair analogy though?

Souta Calling Last: Yeah.

EmbraceRace: Fully European, fully Native, you know having Native ancestry or tribal ancestry traceable in every direction possibly but to not be able to be a member of any tribe depending on how each tribe defines its membership typically with respect to blood quantum.

Souta Calling Last: Mhm. That's a really good analogy. And another analogy to go with blood quantum is, in reverse thinking, is the one drop rule. And so opposite of that, if we have one drop white or "other" besides our ancestral tribe and then we are then diluted and not pure or perfectly Indian anymore. And so just how one drop in the days of slavery was enough to put you into slavery, one drop in the days of enrollment is enough to diminish your realness as a Native person.

Community Q&A

EmbraceRace: We're going to open it up to questions. Let me ask one that I think is really timely here. And just to underline this point is from Rosalyn who says, "Tribes have sovereignty and they get to decide their own citizenship, similar to the U.S. Why don't tribes change their citizenship rules? What's going on?" So what's the incentive for leaving some people out who might be included?

Tyler Walls: That's a great question. And yes, every sovereign nation, and there's 573 federally recognized tribes and an additional 200 state recognized tribes that each have the ability to determine their own membership, essentially the citizenship that makes up their nationhood. There's a number, and I will touch on that but this is a really messy situation. It really is a complicated situation that we know that people won't agree with us but it's okay to have that healthy debate. It's okay to have that healthy conversation to bring this to the forefront of conversation so we stop hiding it somewhere back here because our children, our nieces and nephews, and if we're not impacted by it now, we will be impacted inevitably in the next generation or two.

So why don't tribes just change their membership? Well, you have a lot of opposition to opening up enrollment to everybody. And going back to the Blackfeet. There was a huge debate a couple years ago whether or not removing the one quarter blood quantum rule under the Blackfeet constitution. Well there's a group same pushing for removing that blood quantum rule to allow children, grandchildren who may be less than that, one eighth, one sixteenth, one thirty second and this just goes on and on forever. They felt that their children needed to be enrolled and there was opposition that said, "No we can't. We have to restrict it in a way so we don't have everyone coming out of the woodworks trying to say they are Blackfeet." And did you want to add on?

Souta Calling Last: Yeah.

On one side of the argument, you have a lot of people saying if you open up enrollment to everybody, the tribe is going to disappear and we're not going to be real Indians anymore. And then the other group is saying if you don't open up enrollment we're going to disappear and the tribal will no longer exist anymore because we're all going to be like bred out. It's such a big, hairy situation of both people want the tribe to continue. The devil's advocate part is that a lot of people are saying tribal councils and leaders are making these decisions purely based off of greed and per capita payments. It's just tribal members are viewed as resources. And on the other hand, all of our services, all of our treaty obligations, are done by population. And so for me like the big picture of what's at stake is yes, under the current system, tribes will disappear. We will no longer have enrollable members.

Per cap payouts if the tribe has made some sort of deal with natural resources or gaming and the tribe gets a large amount of money and excess that is not invested in the communities and is given out as payments to tribal members. And so obviously the the less tribal members there are, the bigger your payments are. And so one easy fix to this could be that if you're born after a certain date, you're not eligible for per cap payments. But you don't have the trauma induced by being disenrolled. And the trauma that that causes really is akin to banishment. In Blackfoot culture, banishment is worse than death. And so I think that relates really well to the suicide levels we see in Native populations and youth.

Just the historical trauma we have encountered, the continuing trauma and how disenrollment or non-enrollment, it further compounds the trauma that we face as Native people. And so we won't really be able to live our best life or live it without fear and trauma if we first don't have the support of our communities.

EmbraceRace: I just want to emphasize this or make sure we're drawing out this point about the benefits, right. So the benefits that accrue to membership. And you pointed to a number of things. Tyler, you especially at the beginning, outlined a whole bunch of benefits right. Hunting rights, fishing rights, the rights to fast and pray you know on Native tribal territory and a whole bunch of other things. Schooling, health, all of these things. Souta, you just mentioned the sort of money rights. Federal moneys that come to the tribes based on the number of members that they have. So there are some obvious implications.

And I just wanted to say just a quick word about gaming because I know this was a huge deal. So when various tribes got the rights to erect and run casinos, some of them made a lot of money. The casinos attract a lot of money. So how many people are laying claims to the profits from those casinos was also implicated in this. Is that fair?

Tyler Walls: It is. Not across the board because the majority of tribes don't have casinos. My two tribes, Hopi and Onondaga, do not have casinos. And one of them is by choice. Onondaga Nation Council of Chiefs decided against it because there was more cons that outweighed the pros. Because of dependency on that gaming revenue and all kinds of stuff that goes on with with that.

You look at some of these situations happening in California where they have actually disenrolled members because of casino profits and payouts. A lot of it also is political. If you are able to disenroll or unenroll or not even enroll a family over here, that could be 300 votes that you don't have to worry about. And so therefore absolutely that person is for not enrolling that particular group of people because they may not vote you in or it's against your political platform. So absolutely political and economic.

What it really comes down to is the founding of this country. The founding fathers saw Indian nations as a burden, as a problem. And that's where they enacted the complete genocide of our people, assimilating us into the fabric of society. In the late 1870's, right around that era, they found it cheaper to educate the Indian than to kill the Indian. So rather than actually killing us, they went ahead and educated us, more so assimilated us, through the boarding school process. And so that assimilation process was meant to bleed us out into eternity to where we no longer existed. And because this issue is so hard and tough to talk about, a lot of us don't even address it.

The point that we're putting across is that you may be sided with us, you may not. But what's healthy about it is that we're bringing this conversation and topic to the forefront so we can at least start wrapping our head around because again it is the tribal leaders that are the ones who ultimately have the decision to make.

Souta Calling Last: And personally for me growing up in Heart Butte, we have a ghost ridge which is a site of a mass grave. And so for me, growing up so close to that and seeing that genocide and that trauma is knowing that these people are close to me. They're not too far removed. A hundred, hundred and fifty years ago. They’re relatives, they didn't die for nothing. They can't have died for nothing.

EmbraceRace: We have a comment. Someone wrote in, "As a biracial Indigenous Caucasian adoptee, I have found much of my life confusing, frustrating and have found it hard to describe my frustration to others not experiencing this situation. Although I was adopted into a loving family, being raised by Caucasian parents with no knowledge of how to approach the racism I was experiencing was hard. I cannot tell you how happy I am to see this conversation take place."

Tyler Walls: Our son is blessed and privileged to have parents that are consciously aware of what the situation that we're facing. A lot of people don't have the benefit of parents like me and Souta who able to pass down that information. And I think about our foster kids ...

We've paid a lot of attention in our youth empowerment program to kids in the foster system because they have those ties severed essentially to that knowledge of their community. Not only knowledge but just connections, friendships, even access to land. I myself was raised off the reservation. My mom was raised off the reservation. So I am third generation removed from the reservation. So me and her even have a totally unique upbringing to where she's able to describe the empowering of her mountains that gave her tremendous identity shaping as a whole in her young childhood. Me, I didn't have access to that knowledge because my grandfather Hopi unfortunately passed away too early in our life. My Onondaga grandmother left the reservation at 13. And so she at 13 never went back to live on the reservation. We have family there and we still have ties there. But a lot of that knowledge of her being Onondaga as far as traditional concepts were not passed down to the generations, even to me.

Growing up, I was confused as heck. I knew that my grandma always enforced that I was five nations. I was Onondaga, Seneca, Mohawk, Cayuga, and Oneida. And that that was kind of the limitations of my identity building as a young Indigenous person. It took me to become an adult to really seek out my identity.

And as far as the friends that I gained, college itself opened up my eyes. And being able to secure work at an intertribal organization where I found relatives and family members and just continued my quest of building my own foundation as a Hopi person, as an Onondaga person. So what I say to that person who's Native and adopted by white parents, never stop learning. Continue to seek out information. Continue to learn and always question. Unfortunately even my white father is fragile when we talk about racism and blood quantum and all of this and he sees himself kind of out of the picture in that. But he himself is part of this. He's my father. I love my father and I love my side of my family on that side.

Souta Calling Last: And it's a really complex issue. Like the identity crisis that you face as a Native person is even felt, you know I'm confident in who I am but when I'm in Arizona, I don't really look like any of the Natives in Arizona. And so I'll have people tell me things like, "Go back to Mexico" or "You don't look Native." And I'm like, "Oh because the Native down here look like what?" *laughs* And so there's a lot of complexity with this issue.

EmbraceRace: Thank you. There's actually a very related question to that I want to share with you and see what you think. Actually at least a couple but I'll just name one. So you're talking about an assault on the identities of Native kids and tribal kids. So Lynn wants to know: "What are some childhood experiences that Indigenous folks remember" - or let's say you remember - "as being connecting and grounding for them in your identity?"

Souta Calling Last: So for me as a Blackfoot woman one of our tribal historical figures is Pitamakan, or Running Eagle. She inherited that name. She was formerly known as Weasel Woman. And I just found this sense of empowerment and identity hearing of her and knowing of her, knowing that I come from a people that didn't have such oppressive gender roles. And that as a Blackfoot woman, I could be anything I wanted to be, including a war chief. And so Pitamakan rose through the levels of being a warrior to leading her own war parties and being a huge advocate for Blackfoot territories around Montana and southern Alberta. And she was such a prominent figure in protecting our ancestral homelands that I identify a lot with her and my identity is affirmed through her because I feel like Indian wars have not ended.

I feel like I'm very much a participant in an ongoing genocide and continued historical current trauma. I feel like Native people haven't fully recovered from the genocide and the trauma that has happened in the last five hundred years. As a Native woman, I have a responsibility to protect my people and protect my family. And so knowing of Pitamakan, growing up around her story, seeing landscapes where she might have had a battle and finding Tomahawks and hammers and war weapons in these areas where the stories are related is so different from learning in a book or learning about history as a separate thing. Everything about being on my ancestral homelands created this power in me and this confidence that no matter where I'm at in this world, as long as I know that my mountains are standing and I know those stories of the mountains and the power that lies within that landscape, that I also feel equally powerful.

EmbraceRace: Bring it home to your son if you're willing. You're Hopi. You're Blood. Your son is neither.

Tyler Walls: To correct you, he's everything. He's Blackfeet, Hopi, and Onondaga.

Souta Calling Last: *laughs* He's the Holy Trifecta.

Tyler Walls: But on paper, he's not.

EmbraceRace: How do you instill, how do you push back against that threat to your son?

Souta Calling Last: Well he knows a lot of Blackfoot language. I can speak conversational language with him throughout the day and he understands. We travel a lot every year to sacred places or significant places within our history as a Hopi, Onondaga and Blackfoot. And he can tell those stories, the origin stories and the language that accompanies that.

Tyler Walls: Our goal with our son is to build him to be the most powerful Blackfoot Hopi Onondaga person to where all three of our nations are going to be like, "We want him."

Souta Calling Last: *laughs*

Tyler Walls: It is so true though. Our son is blessed and privileged to have parents that are consciously aware of what the situation that we're facing. And I wanted to touch base, go back to the comment that you read. The individual who was adopted who was raised by white parents and was always questioning his identity. And that itself is, we see that where a lot of people don't have the benefit of parents like me and Souta to our child to be able to pass down that information. And I think about our foster kids.

That's why we've paid a lot of attention in our Youth Empowerment program to youth in the foster system because they have those ties severed essentially to that knowledge of their community. Not only knowledge but just connections, friendships, even access to land. I myself was raised off the reservation. My mom was raised off the reservation. So I am third generation removed from the reservation. So me and her even have a totally unique upbringing to where she's able to describe the empowering of her mountains that gave her tremendous identity shaping as a whole in her young childhood. Me, I didn't have access to that knowledge because my grandfather Hopi unfortunately passed away too early in our life. My Onondaga grandmother left the reservation at 13. And so she at 13 never went back to live on the reservation. We have family there and we still have ties there. But a lot of that knowledge of her being Onondaga as far as traditional concepts were not passed down to the generations, even to me.

And so growing up, I was confused as heck. I knew that my grandma always enforced that I was five nations. I was Onondaga, Seneca, Mohawk, Cayuga, and Oneida. And that that was kind of the limitations of my identity building as a young Indigenous person. It took me to become an adult to really seek out my identity. And as far as the friends that I gained, college itself opened up my eyes. And being able to secure work at an intertribal organization where I found relatives and family members and just continued my quest of building my own foundation as a Hopi person, as an Onondaga person. So say to that person who's Native and adopted by white parents, never stop learning.

Continue to seek out information. Continue to learn and always question.

Unfortunately even my white father is fragile when we talk about racism and blood quantum and all of this and he sees himself kind of out of the picture in that. But he himself is part of this. He's my father. I love my father and I love my side of my family on that side.

Souta Calling Last: And it's a really complex issue. Like the identity crisis that you face as a Native person is even felt, you know I'm confident in who I am but when I'm in Arizona, I don't really look like any of the Natives in Arizona. And so I'll have people tell me things like, "Go back to Mexico" or "You don't look Native." And I'm like, "Oh because the Native down here look like what?" *laughs* And so there's a lot of complexity with this issue.

EmbraceRace: So we have to wrap up here and there's so many questions. I'm wondering about, we're sort of going for wrap up thoughts here perhaps in response to a question which is we're getting a lot of questions related to what to do to feel strong in your identity, about what to do for kids in particular. You have questions from folks who are not connected to Indigenous culture raising Indigenous kids. A question, Diane: "From your perspective, how can white mainstream, or I would say non-white mainstream people, support Indigenous culture and with this particular issue if we are living in areas without any substantial Indigenous populations?"

Souta Calling Last: Right.

EmbraceRace: So I guess some words about what people can do with kids in their lives facing these issues or it's a part of broader society to sort of make it make it better.

Souta Calling Last: So if you're just a concerned neighbor, go around your community, go around your state and see what kind of narrative is being told about Indigenous people and the original people. In the schools make sure they're not telling the false narrative of Thanksgiving. That they're not doing stereotypical imagery in terms of mascots and turkey feather head dresses. That if headdresses are being sold anywhere that those aren't things to be sold or worn as costumes so there's a lot of things that Natives and non-Natives can do to kind of relearn and check the misjudgments that we have as a society right now.

In terms of raising a child that has a strong Native identity, there is nothing that can replace actually visiting ancestral homelands and learning the origin stories. So there's no book. There's no movie. There's no group that I can think of that could replace the benefit of having your children's toes in the soil that they were formed of and from.

In terms of general society, I would love to have people put a little friendly pressure on their elected representatives to make sure that they're making sound decisions that are promoting healthy Indigenous communities and intact cultures. And so that's a lot of environmental aspects and making sure that we have an intact environment to sustain our culture. So that's all included on the tip sheet we made for you all.

EmbraceRace: Thank you so much. We are going to send you any resources these guys think of including this great tip sheet they made. I want to send a shout out to, we had Debbie Reese on a couple webinars ago and her book came out today which is actually Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's version of her book that she wrote with Jean Mendoza called An Indigenous Peoples' History for Young People. So that's something to look for and buy, to get in your schools. And we had another book about disenrollment called Indian No More that we will also put in the resources. It's not coming until September but shout out to the writers of that book and Lee and Low Books.

Tyler Walls: Yes. If I could just say a couple of ending words. And Dr. Reese, she said it best ever in her conversation with EmbraceRace in May. "If you have no children, you cease to exist as a nation." And that's really what we're hitting on is it's important to have children in order to make up our tribal nation. Because of this conversation, there's so much to cover and I feel that we barely hit the surface of it. We want to continue the conversation so feel free to reach out to Indigenous Vision, IndigenousVision.org. Email us at info@IndigenousVision.org and we would love to answer your questions.

EmbraceRace: Just want to thank you Souta Calling Last, Tyler Walls. Excellent conversation. Such an important set of issues, complicated. I think you did really well to breaking it down to some of the really crucial bits. And bringing a lot of heart. It's clear your own investment. We wish you the best, certainly with your son and as he develops and that he becomes that person that they all want, that all three must have. They'll be fighting over him. The implications hopefully for so many of his peers and for the future of the tribes.

Related Resources

Evaluation of a Native Youth Leadership Program Grounded in Cherokee Culture: The Remember the Removal Program

By Lewis, M. E. ., Myhra, L. L. ., Vieaux, L. E. ., Sly, G., Anderson, A., Marshall, K. E., & Marshall, E. J. (2019).

American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center

Indigenous Social Justice Pedagogy: Teaching into the Risks and Cultivating the Heart

Shirley, V. J. . (2017).

Critical Questions in Education, 8(2), 163–177.

Curing the Tribal Disenrollment Epidemtic: In Search of a Remedy

Gabriel S. Galanda and Ryan D. Dreveskracht

Native American Bar (2014)

US Department of Indian Affairs

Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs

So what exactly is 'blood quantum'?

Kat Chow

NPR

The difficult math of being Native American

Savannah Maher

NPR

Resources for Kids

An Indigenous Peoples' History for Young People (Penguin, 2019)

Adapted from Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's original history by Debbie Reese and Jean Mendoza for middle grade and YA readers.

Indian No More (Lee & Lowe Books, September 2019)

By Charlene Willing McManis, Traci Sorell

"Regina Petit's family has always been Umpqua, and living on the Grand Ronde Tribe's reservation is all ten-year-old Regina has ever known. Her biggest worry is that Sasquatch may actually exist out in the forest. But when the federal government enacts a law that says Regina's tribe no longer exists, Regina becomes "Indian no more" overnight--even though she lives with her tribe and practices tribal customs, and even though her ancestors were Indian for countless generations."

Souta Last

Tyler Walls