How Kids Learn About Race

So often, when we at EmbraceRace introduce our work to someone new, the response includes something along the lines of, "Wonderful! I'd love help knowing how to talk to my kids about race!" However, the truth is that what adult caregivers say explicitly to children about race, when we say anything at all, forms only a small part of what children learn about race.

On this episode of Talking Race & Kids, we take a close look at the childhood landscape of racial learning. Beyond what we say to them explicitly, what other factors shape what our children learn about race? How do differences in racial and class identities shape the ways children learn and are taught about race? Professors Margaret Hagerman and Erin Winkler share their research then Andrew and Melissa of EmbraceRace take questions and comments from the EmbraceRace community (you!). The transcript of this conversation follows. Further down you'll find the Community Q&A, then related resources and lastly guest bios.

EmbraceRace: Welcome! I want to start by saying that for EmbraceRace, the topic of tonight’s conversation is the core issue for us. Namely, how do children learn about race and what can we, as the adults in their lives, do to support that learning in a healthy, thoughtful way? Both our guests are experts on that and their work compliments each other in a way that's super, super useful. Maggie, want to say what's up, Maggie?

Maggie Hagerman: Sure, sure. Hey, I'm Maggie [Hagerman] and I live in Mississippi. My research focuses on white families and white children and so I've spent a lot of time with kids and with their families trying to understand some of the challenges that their parents face; and some of the ways that the kids are making sense of racism, and learning racism, and learning to challenge racism. And I've always loved EmbraceRace since you first got started! And so it's really fun for me to be on here tonight. And actually the other guest, Erin [Winkler], is one of my academic heroes. A lot of my research builds on hers. So this is really special for me tonight.

EmbraceRace: What Maggie didn't mention is that she recently published a book that's getting a lot of play - it's called White Kids: Growing Up with Privilege in a Racially Divided America -where she explores how white children learn about race in the context of their everyday lives. She's been all over the airwaves and her written work has been all over in some really significant venues. The Atlantic, The Guardian, L.A. Times, and more, on the radio. All of it. Thank you, Maggie we're really delighted you're here.

EmbraceRace: And Erin, so glad that you're here as well. We've drawn on Erin's work a ton. I'm going to let you say a word about yourself in a second, Erin, let me just give some of the basics. You are a professor of African and African Diaspora Studies and Urban Studies at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. I think Melissa mentioned this here before. We started reading Erin's book recently. The book is called Learning Race, Learning Place: Shaping Racial Identities and Ideas in African American Childhoods. She recently consulted for the National Museum of African-American History and Culture working to train museum staff to have productive conversations about race and racism with visitors of all ages and backgrounds.

There’s much more that could be said. Erin, did you want to add anything?

Erin Winkler: Sure. Like Andrew said I live in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and I've been in African American studies my whole academic career since I was a freshman. So that's since twenty five years. [Laughs] But I often get the question you know how did a white woman like you end up in African-American studies? And I go back to my childhood. I grew up in a predominately white college town that liked to think of itself as pretty liberal and not having “those kinds of problems” here and even my earliest memory is as a six-year-old wondering, okay, well the adults say everyone is treated equally but that's not what I see around me. So my interest in this started as a child. And I was interested in how do these ideas about race that people have, how did they come to be in the first place? And so that's how I got interested in studying how we all develop our ideas about race, our racial identities, and how children especially, for me African American children, negotiate racism in their daily lives.

EmbraceRace: Erin, thank you. I'm going to hand it to you, I think, to start.

Erin Winkler: Okay, so thank you so much to all of you for being here tonight. We really appreciate you. I'm super excited to be here with Maggie. I'm so impressed with her work. I love EmbraceRace! So just thanks to all of you for being here.

Maggie and I decided that we wanted to structure our time today by interrogating some commonly held myths or misconceptions about how kids learn about race. And so we've broken it down into four main myths. So we're going to talk about each myth in turn and explain why although these things seem like they should be true or they seem like common sense, they're actually false.

And then we also want to share with you, so given this research, what are some ways in which we can and should be engaging kids about race? And of course we will also spend most of our time tonight on question and answer. But Maggie and I really want to focus on these four myths. So Maggie's going to start it off with our first myth.

Maggie: So this myth is one that I often see in the aftermath of, for example a racist hate crime. I see all kinds of blog posts and newspaper articles and op-eds written about how it's really important to talk to your kids about race. And I think that while, certainly, what parents say to their kids about race is meaningful, so, too, is what they do. Both in my research, but as well as Erin's research, we really find that actions speak louder than words. I think that's a really important kind of idea that can debunk this myth.

And so in my research on affluent white families, I find that behaviors like how to respond when grandpa says something racist at Thanksgiving. Right. How parents choose to respond to that is a way in which they’re modeling behavior to their kids. That action is really powerful - what they do or what they don't do. And even silence can be a form of modeling.

In addition, choosing neighborhoods where you live, where your kids go to school, the friendship groups that you either encourage or even discourage, the extracurricular activities that you enroll your children in, and so forth. These things, I show in my book and in my research and again building on Erin's amazing research, really speaks to how a child's racial context is set up. And I think Erin's going to talk a little bit more about this in a moment, but I do think that at least when it comes to white parents, for example, when white parents are consistently hoarding opportunities for their own children through the choices that they make about for example schools, and they fail to see that this is connected in some way to racial power. It's the perpetuation of racial inequality. Then I think you can really see how even though parents might say one thing about what they think about race, their actions are actually conveying something very different. And in my book, I show how sometimes even you know their behavior is actually contracting or contradicting what they say that they believe. And this you know against actions speak louder the words.

Maggie Hagerman: Right. So this myth is one that I often see in the aftermath of, for example a racist hate crime. I see all kinds of blog posts and newspaper articles and op-eds written about how it's really important to talk to your kids about race. And I think that while, certainly, what parents say to their kids about race is meaningful, so, too, is what they do. Both in my research, but as well as Erin's research, we really find that actions speak louder than words. I think that's a really important kind of idea that can debunk this myth.

And so in my research on affluent white families, I find that behaviors like how to respond when grandpa says something racist at Thanksgiving. Right. How parents choose to respond to that is a way in which they’re modeling behavior to their kids. That action is really powerful - what they do or what they don't do. And even silence can be a form of modeling.

In addition, choosing neighborhoods where you live, where your kids go to school, the friendship groups that you either encourage or even discourage, the extracurricular activities that you enroll your children in, and so forth. These things, I show in my book and in my research and again building on Erin's amazing research, really speak to how a child's racial context is set up.

And when it comes to white parents - when white parents are consistently hoarding opportunities for their own children through the choices that they make - about, for example, schools - and they fail to see that this is connected in some way to racial power. It's the perpetuation of racial inequality. Then I think you can really see how even though parents might say one thing about what they think about race, their actions are actually conveying something very different. And in my book, I show how sometimes even their behavior is actually counteracting or contradicting what they say that they believe. Again, actions speak louder the words.

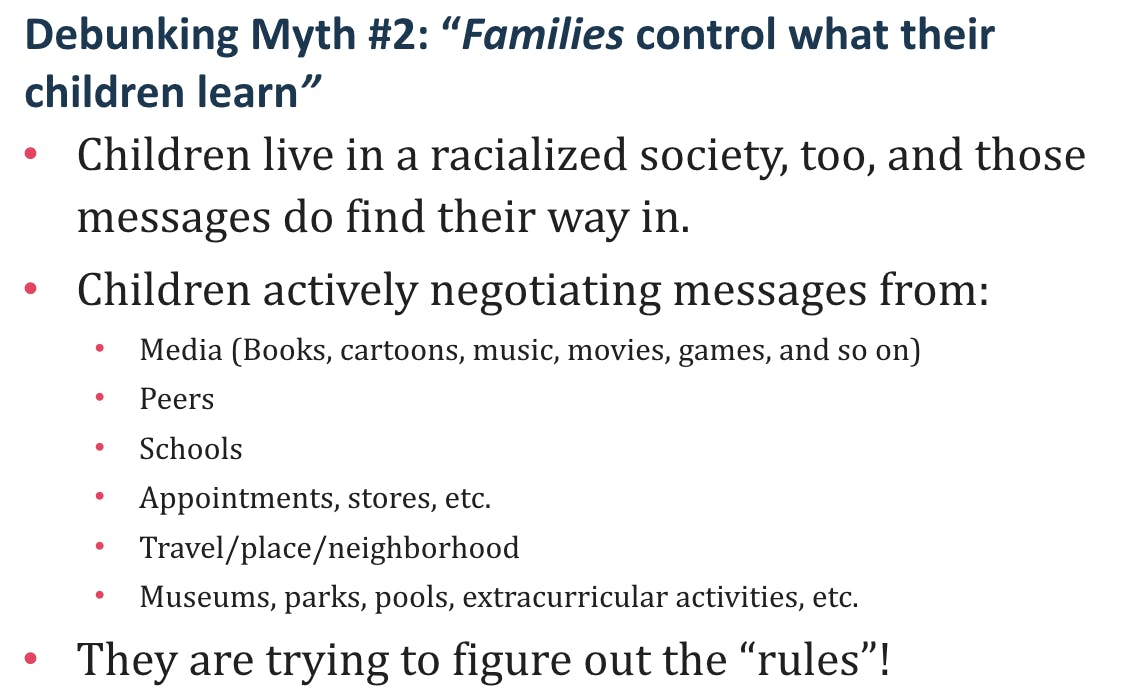

Erin Winkler: Okay, so our second myth is that families control what their kids learn. I don't know if you all have experienced this as parents or families with kids, but usually if there's a racialized behavior or comment on a child's part, immediately the blame goes to the family. People assume it must have been the family that gave the child this idea. This is a myth that we want to debunk.

Certainly families play a big role. And parents may wish to limit their children's exposure to racism, or they may wish to avoid having discussions about race. But the truth is that children live in the same racialized society that all of us live in and they are getting messages about race from all around them every day.

So often parents will say to me, "Gosh my kid is only three. They're only four. They're too young to talk to them about this. They don't notice it yet." But what research shows us is kids are noticing racialized patterns in the world around them and they are trying to figure out those patterns. Those messages are getting to them from a whole variety of sources, not just from families.

They’re getting it from media, books, cartoons and so on and so forth. Toys. Now maybe you'll say, "Well, I don't let my kids watch TV. I don't let my kids watch Disney movies so media isn't getting into my kids." But when your kids go and play with other kids, they might see that Elsa princess on the T-shirt or the backpack or the toy or on the sleeping bag at the sleepover. So even if you try to limit your child's exposure to some of these things, those messages are really getting in from these other sources.

Or let's say that you protect your child from discussions around race and racism but they go to a school or a daycare or the doctor's office or the grocery store and they see there who seems to have what kinds of jobs. Are there any racialized patterns in the power hierarchy? Now your 3-year-old isn't saying, "Are there any racialized patterns in the power hierarchy?" But they are noticing patterns. Who seems to be the most popular princess? They are getting those messages from the world around them.

And both Maggie and I in our research do a lot around place, how place itself really sends messages to kids about who belongs where, who gets what kinds of houses or who gets what kinds of stuff. And so even if they ride or walk through neighborhoods in your area or your city, they are getting messages about patterns that they see that seem to revolve around skin color or race. And then they also, if they go to museums or other kinds of extracurricular activities, they're getting ideas about who belongs where but also about whose ideas or artworks or discovery or contributions are really being held up as most important or worthy of recognition.

And so from all of this, they're picking up on patterns. We shouldn't be surprised that young kids, we're teaching them to recognize patterns. We want them to match their shapes and their animals and you know match things and learn patterns but they're trying to figure out the rules from those patterns that they see around them. So families often think that they alone control what children learn. But these messages come from all over.

Erin Winkler: Now that doesn't mean that families don't play a role. Families can help their children process and critique the racialized messages that they're getting from all of these places. But we often think we're protecting children by avoiding talking to them about race or exposing them to certain things. But when we do this, what we're actually doing if we're silent about race is we're letting racialized messages from society seep in and become ingrained. So they see those patterns, and if we don't help them understand why those patterns exist and that those patterns aren't earned or justified, they tend to think of them as rules and rules that are caused by inherent differences between people. And this is what our research shows that these ideas are ingrained by about three years old, three to four years old. So children are internalizing messages from the world around them by the time they're in preschool. But adults can help disrupt this process and we will talk a little bit more about that in your question and answer time.

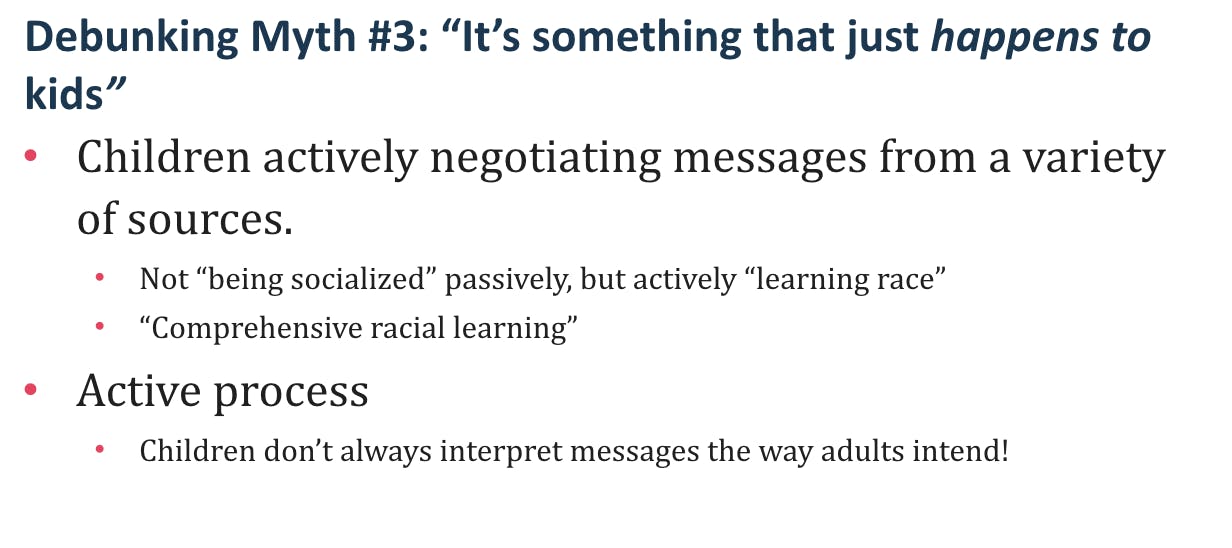

Erin Winkler: Myth number three is that this is something that just happens to kids. So in actuality what's going on is that children are really active in this process. They are actively negotiating messages from a variety of sources. Often children are thought of as empty vessels or blank slates into which adults or other sources are just pouring ideas or onto which adults are inscribing ideas. But instead our research shows that children are not at all passive in this process - they're actively negotiating the messages that they receive. When I first started researching this topic, all of the scholarly literature I was coming across was talking about children being socialized or being racially socialized or parents socializing their children. So parents were conceived of as active in this process but children were really framed as passive. But also what was happening was that the focus seemed to me in the research to be on the sources of the messages. The research was concerned with the parents or the media or the schools, the sources or the message. But no one seemed to really be centering on the children and how they were negotiating all of these messages and actively deciding you know, how to interpret these messages.

And so that's why I created this framework called "comprehensive racial learning" because I wanted to do two things. First, I wanted to sort of deal with what we talked about just in myth number two that notion that it's only parents. And I wanted to instead say actually, it's a variety of sources that are involved in this process with kids, from which children are receiving messages.

Erin Winkler: But second, I really wanted to center children and say, you know, children are at the center of this process and they are very active in this process. So instead of being socialized, they're learning. They're engaging in a learning process. And so let's think about how they receive these messages. How do they make decisions about how to interpret these messages and what to filter out or reject or keep and so on or modify, however they're sort of involved in this negotiating these messages. So racial learning is really an active process. Kids are actively participating in this.

And this also means that children don't always interpret messages the way that adults intend. So for example many parents will send colorblind messages like, "We don't notice color because we're all the same on the inside." The parents intent in this is a really an egalitarian message, that everyone is equal. But research shows, perhaps counterintuitively, that these colorblind messages increase racial bias in children. Because what happens is the take away message for them is they see racialized inequities in the world around them like we've discussed. They see racial patterns, but if they're told everyone's the same, then they often interpret these racial patterns not as unfairness but as something that's been earned or something that's deserved or justified. So in fact colorblind language increases racial prejudice in children.

Now from my research with African-American children in Detroit I have tons and tons of examples of families thinking they're sending one kind of message and children interpreting another. But I'm just going to share one with you here. Just a brief one here. So here's a quote from a 13 year old in Detroit, Michigan and she says, she's asked if the adults in her life talk to her about race. And she says:

"In a way they do. Because my grandma had adopted some foster kids and they was white but they wanted to be black. My grandma was telling them how if you want to be black men then some black man's don't get everything that a white man gets. But my grandma said if you have a chance to pick if you was white or black to go white because white people have special just access to stuff, but I really didn't understand what she was saying but I do. I do but I don't. Because to me she will say stuff like you should be proud to be black. So I'm like okay..."

So here's an example where the grandmother intends to send some important messages and some common racial socialization messages. One is about how white privilege functions in society. And the second is about the importance of having black pride. And yet here we see her granddaughter isn't just an empty vessel or a sponge soaking up the message exactly how grandma intends. Instead she's interpreting it in relationship to other messages she's received other experiences she's had across time and place. So I'm sure Maggie and I both have lots of examples of this but the basic idea is kids are not blank slates or empty vessels here. They're actively interpreting the messages they receive.

Maggie Hagerman: And so the fourth myth that Erin and I came up with is this notion that families of color have this figured out. And so one of the things that I certainly noticed in talking to white parents, in fact, when I was trying to recruit participants for my book, I would ask white parents to participate and they would refer me to their black friend or their black neighbor and they would say, "Oh well, they know all about how to do this, so you should go talk to them," which is an interesting indication that white people don't think that they have race sometimes. But I think that the message here is this idea, this myth, that somehow, magically, people raising black and brown children somehow have this figured out. And so I think that before I go deeper into this I think it's really important to say from the from the very beginning that of course given the racialized nature of our society.

Sociologists are thinking about hierarchies and power and history and all of that. And it's very clear that families of color face an unfair and unjust burden raising children in America and they have to make difficult choices for sure. Erin alluded to some of the challenges including that example with the grandmother that she just read. But you know, thinking about how to talk to your kids about things like anti-blackness and about racism and about racial violence and about current events and, you know, how do you have those conversations?

And so what the research shows, and I should say that this is an area that's really growing both in fields like human development and family studies. But also in sociology and a number of other fields as well. And although I study white families and although Erin has studied African-American families, certainly this is not just the white family, black family situation and in fact there is a tremendous amount of research that's emerging, and really has been over the past few decades, that's looking at Latinx families, Asian American families, mixed race families, biracial families. And so on certainly tonight we don't want to paint the picture that this is just about white families and black families. Obviously that's not true.

So what we do know from the research though is that there is no uniform approach. When you look at the scholarship, and there's some really great reviews of the literature, there's one by Diane Hughes for example who's a psychologist. She shows how across a range of different studies, we see that there is no uniform approach in families of color and in particular in African American families, which is where a lot of this research initially emerged for really important reasons. And so this is where this question of how to make choices and decisions about approaching this process come into play.

I talk to my students sometimes about racial socialization and what they remember, about their comprehensive racial learning. And oftentimes, especially if they're themselves a person of color, about the fears that they have thinking ahead into their future about how they will raise children in America. So this myth that somehow magically families of color have this figured out is absolutely misleading.

Maggie Hagerman: And one of the really powerful lessons from Erin's research, as well as from others, is that context really matters. Thinking about where families are living, thinking about local dynamics, thinking about current events, thinking about the racial and political landscape of communities. I think all of these things are really important. And I don't think that there's any clear direction.

Later we’ll talk about some tips that we have but I think that it’s a really complicated and messy thing that we're talking about. But certainly the research shows that there's not just one way. There's not just one way that families of color approach this. I should add also that there are some patterns, like we know patterns about age for example. Like parents tend to talk to kids about different things, different ages or tend to not talk about things at different ages. And then there's also patterns around you know teaching racial pride or maybe even teaching colorblindness as Erin alluded to. So again, a range of different approaches. It's not just this one thing.

Community Q & A

EmbraceRace: Thank you both for that. We’re getting a lot of questions in. Before going to the questions, I did want to follow up on a thing that you Erin said in particular because it does have to do with what we know and how we know it. And what you said was that you know by age three that racial attitudes are ingrained. Right, so value driven racial attitudes. Can you just say more about what is happening you know roughly around age three.

Erin Winkler: Right. So I don't want to make it sound like it's permanent and can never change but what the research really reflects very consistently is that by age three, children are showing a pro-white bias. At age two and a half, we see in the research with toddlers of all races what we would call an in-group bias. So there's some things going on internally, cognitively, in what they're thinking, that makes them tend towards an in-group bias. And the studies that look at this look at things like how children pick a potential new playmate. So showing them photos of kids that they don't know of their race and of different races and younger kids tend to choose a same race playmate.

Many of the studies show that by three or four, the white kids continue to choose a white same-race playmate, but the children of color start also choosing a potential white playmate. So instead of like this in-group bias remaining, we start seeing all of the kids shifting towards a pro-white bias. And so what researchers think is going on is that those messages from the world around them are getting in that they’re learning it's better to be white. The heroes are always white. White people get nicer stuff. You know these kinds of messages are coming in from the world around them.

Now adults often think that three-year-olds are too young to talk to about these things. But when we don't talk to them about it they see those patterns in the world around them and they internalize them as deserved or earned or justified. And so in fact when we use colorblind language or silence with kids that young, we actually give up our power to the messages coming from society. And so this is why I really try to encourage parents and we can talk about some ways, to talk to a three or four year old about the patterns that they're seeing in a way that they're able to question them and critique them

EmbraceRace: Thanks for that. That makes me think of an article by Michelle Wallace (and have not been able to find since). She wrote Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman all those years ago. In this particular article, she talked about the doll test, you know, and about how black and white children were favoring white dolls. And her response to that was, well they know the right answer! Is there a little bit of a difference between expressing a preference for the white doll and getting the right answer, according to the world around them?

I’m also going to fold in a related question we got from a parent whose child, a black/white biracial child, was identifying as white and is sort of light-skinned but seemed to have a preference for white characters. And I don't know how old the child was but they were talking about his reaction to the characters in the recent movie A Wrinkle in Time. Given that, let’s guess the child is eight, ten. And the parents were upset, you know, "Why is my child favoring whiteness?" What would you say, either of you, to that parent?

Erin Winkler: I don't know if you're familiar at all with the research of Kerry Ann Rockquemore. She and her coauthor, Tracey Laszloffy, have a book called Raising Biracial Children. And in that they have a model they call the COBI model, The Continuum of Biracial Identity - they're talking specifically about biracial children who have a black parent and a white parent. And they make the argument that a child could have a healthy biracial identity that leans more white or leans more African-American, or even where they identified exclusively as one or the other - as long as they came to it from a healthy place of not denying one side or the other. So that might be an interesting book to read or an argument to engage. For them, it’s less about the identity that's ended up upon and more about the process to get there and whether or not it involves denial of one side or the other.

But I think what I hear you saying, Melissa, is that you're sort of reflecting on the fact that, okay, what do we expect of children who are raised in a society that is continually privileging whiteness in all different realms? And we've named a few, but there are many different realms. And it's constantly sending this message that whiteness is better in many different ways or that it's easier to be white or better to be white or all these different things, then should we be surprised when children choose the white doll? Or should we be surprised when children choose the white heroine in the film or those kinds of things because they're getting those messages. And it's unhealthy for all kids but I can see how you know it feels especially unhealthy for parents of color.

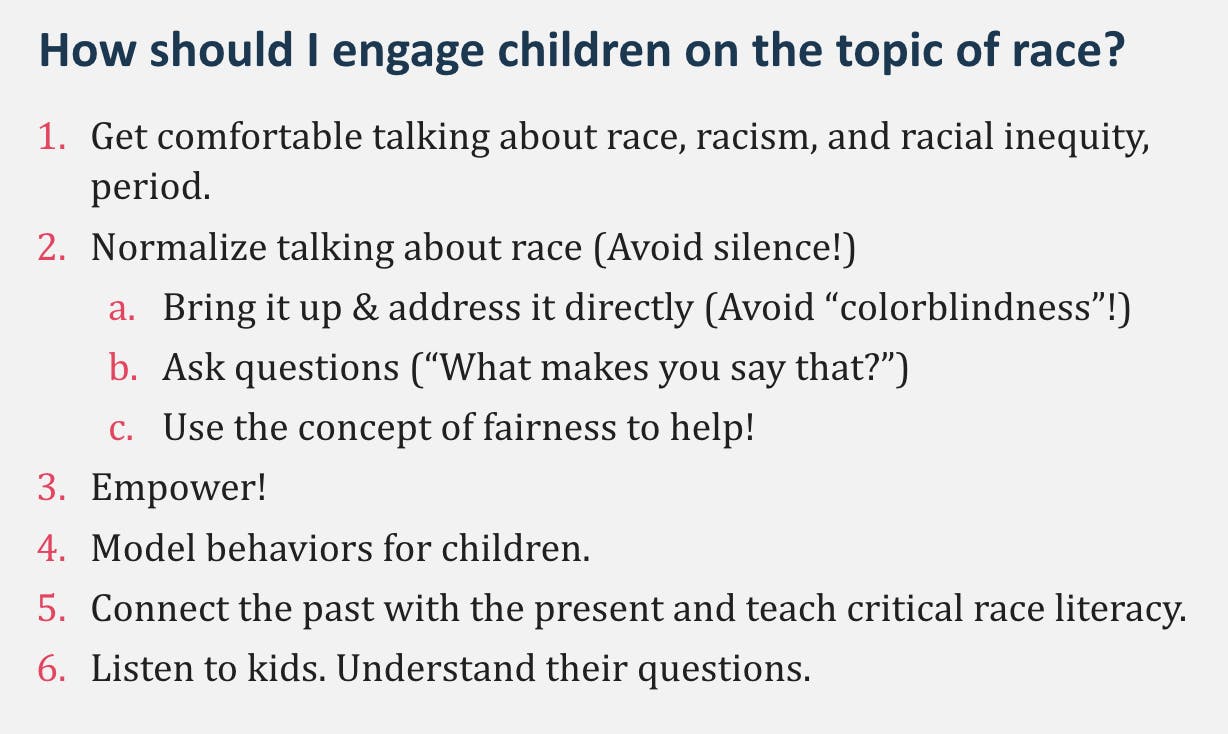

And this is why, because those ideas are getting in so early, we think three is not too young to talk with kids about this. That's the age at which we know that these ideas are reflected in their choices. And so this is why we have to recognize, even if we think we're protecting them. They see patterns in the world around them and we have to explain to them that those patterns are because of unfairness. They're not because of inherent differences or earned or justified differences. They're because of unfairness and they're because of social unfairness. The good thing here is kids are very into what is fair and what is not fair, right. If there's one thing kids have, it's a very keen sense of justice, so we can use this notion about fairness to help them understand these patterns that they're seeing.

Usually the question that I get is sort of like how do you explain this in age appropriate ways, and that depends on the age of the child but there's age appropriate ways for three-year-olds, four-year-olds, eight-year-olds, … thirteen-year-olds to talk about the unfairness in the world around them and that helps them critique it. Instead of subconsciously internalizing those messages that they're bombarded with over and over, both obvious and subtle, about whiteness being better, instead you're teaching them to recognize those as false messages based around unfairness and to critique them. And soon they're able to do that on their own.

Here’s the thing though. It's not responsible for us to teach kids about unfairness without also empowering them and showing them that there are people working to make change and that they can be part of that change. Because otherwise you're essentially saying - and this can be really damaging especially to children of color - "Sorry life is totally unfair to people of color. Okay. Sleep tight." That's going to be scary and just really demoralizing. And so that's why we always always always always teach about unfairness but link it to empowerment.

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Erin. Maggie, I want to take this next one to you because actually it's a case in point of a child recognizing patterns and you know we have a specific age of the child in a specific situation. And I want to offer one little twist, I'll read this and I'll offer a little twist which is it's not clear here what the racial identity of the child is. So I'm wondering, if you know from your perspective, if that makes a difference in exactly how you frame the answer. The question is this. This is from Sasha who says, "My nearly 6 year old daughter recently commented about how back in the '60's, brown skinned people had to sit in the back the bus but she's noticed that nowadays it's mostly brown skinned people that drive the bus. She acknowledged that it's been a while since she last rode a city bus. I affirmed her comment but how could I help her further process the facts of what she was noticing and reflecting on?" Again, what's your basic answer to that, and does it matter the racial identity of the child in this case for what you would say?

Maggie Hagerman: Yeah that's a really great question and it's interesting that this is an example that came from a family because actually in my book similar types of things emerge particularly with this idea of buses and segregation, you know, formal segregation of the past but also patterns today that this child is noticing with who drives the bus. So I think that from a racial learning perspective, I think that regardless of the racial identity of the child they're noticing patterns as they go about their everyday life.

But I never want to center whiteness or assume that a white child noticing that is the same as a black child noticing that, just given the history and the perpetuation of anti-blackness in America. So I think that it's important to acknowledge that reality. But in terms of the process of learning I think that you know it's about noticing patterns, like Erin was explaining.

I did this ethnographic study with 30 white families and, in at least in a couple of those families, I observed a very similar thing happen. And I also observed parents responding to that in different ways. In fact, in the very beginning of my book, it's like in one of the very first quotes from a child, she confuses Rosa Parks with Eleanor Roosevelt and she talks about how Eleanor Roosevelt sat in the back of the bus and she was African-American and everything's good now but it used to be really bad. And as she said that to me, her mother sat by and listened and nodded her head and affirmed her daughter and never corrected her or provided any context.

And there was another mother that similarly used the film The Help, which you know historians have talked a lot about how problematic that film is. I mean it's not a film they should use to teach children about domestic work in the south during Jim Crow. That's not what you should do! But she was trying to use the movie as a tool to guide her children's understanding of the history of racism in America.

So I think the best way to handle that is to affirm the child's experience and what they're noticing. I'm really big on listening to kids and trying to understand where they're coming from and why they're noticing things and how they're thinking of that. So maybe some follow up questions such as, well do you want to talk a little bit more? And … what do you think that means? Why do you think this is true? And then educating yourself as an adult and being able to provide children with that history so that they understand the history that came before today.

I think that too often, people don't want to talk to their kids about history. But children are not going to reach any other conclusion sometimes than the ones that we might identify as racist because they don't know the history that's come before. And so I really think that it's important, and I noticed with the white children, that those who had a better grasp on the multicultural history of America and the history of white supremacy in America were much more, they had the tools to then be more critical in the moment of today.

EmbraceRace: Yeah, thank you. David asks, "Can you reflect on the pluses and minuses of putting students into a racially diverse school when many schools are systemically racist towards people of color. So the experience of witnessing the systemic racism at school versus the importance of being in a diverse environment six to seven hours a day?" I know both of your research is mostly in segregated communities so I don't know how you'd respond to this and if you want to take it?

Erin Winkler: Did David specify race of child or no?

EmbraceRace: No, I think a child of color but not more specific than that.

Erin Winkler: I'm sure folks have seen that there's been a lot of news stories lately about African American families in particular choosing to home school for not the same reasons that traditionally families have chosen to homeschool but more to sort of deal with systemic racism in schools in the form of disproportionate discipline and suspensions and expulsions starting at preschool age, or a Eurocentric curriculum, or implicit bias in teachers, or you know all these different kinds of things. There has been some movement of people of color saying, why are we subjecting our children to this? So I hear a little bit maybe of that in David's question, you know is it better for a child to get this kind of experience in an integrated setting because those are the kinds of things that they will have to be negotiating in their adult life, most likely? Or is it better to not subject them to that kind of Eurocentric environment that's not going to fully value them and their intelligence and that has bias on standardized tests, and in racialized tracking and all different kinds of things?

I will say in my own research in Detroit parents had different points of view about this. Both parents, all parents in the study thought that raising their children in Detroit, which was at the time 86 percent African American and still is the major city in the U.S. with the highest proportion African American population by far. For comparison, I think New Orleans and D.C. are around 66 percent. Detroit's more around 86 percent. All those parents thought that the fact that their kids were being raised in a predominately black city - where the mayor was black, the police chief was black, the school superintendent was black, most of their teachers were black - was really sending their children a message that normalized blackness and black culture and black experiences in a particular way that was unique, they felt, within large cities in the United States. But parents had different views about whether this was protective or basically playing a mean joke on their kids.

Some parents thought, Look this is a gift I'm giving my child. They don't have to explain who they are. They don't have to deal with teachers who think they're less than and so on and so forth. A quote from one mother named Audrey was something about how they see their people moving around and doing it for themselves. But a whole other set of parents thought, OK it might be protective for now but eventually it's going to hurt them because, as one mother said, "This isn't real life. Real life isn't like Detroit." So I think that's again an example of what Maggie was saying about the unfair burden placed on parents of color. They're between a rock and a hard place. Which choice do I make for my child? Neither is a perfect sort of choice. So which choice I make for my child? So I'm afraid I haven’t given you an answer - a you should do this versus this - but more thinking about the factors that go into that kind of decision.

EmbraceRace: This is great and I want to come back to one of the points that you made in the presentation was that the racial context, the racial environment includes much more than what parents say or simply things that are said. And one of the things I wanted to dig in on a little bit more and maybe go to you Maggie, is this issue of modeling. Right so adults and parents in particular are modeling for small children and we touched on this already but I wonder if you could say a bit more about what that might look like or the sorts of things we use as adults in the lives of children might think about when we think about modeling. I know you worked with affluent, white families. Can you give some examples of things that the more thoughtful, deliberate adults in those families, the choices they made that resulted in modeling for their children?

Maggie Hagerman: Absolutely. So the children that I interviewed and that I spent two years with them, and their families, were all in middle schools. They were between ages ten and thirteen. And so I noticed all kinds of things when they were that age. But then I also went back and re-interviewed a subset of that sample when they were at high school. And so I was able to see them a little older and certainly they were more confident in their positions and their sense of racial views. There was a lot of things that happened in the United States during their childhood with respect to race, such as the Black Lives Matter Movement.

And so what I thought was particularly striking, and I promise this is answering your question, is that for the kids who are living in a more integrated and meaningfully integrated with equal status, contact and all kinds of things, that when they were living in that context, then when they were a little bit older and they were confronted with for example police violence. There was a tragedy in this community where this officer killed a black boy, a black teenager. And it was really interesting to see how these white kids from this more integrated space, as a result of their parents modeling this kind of behavior, were much more critical of what was happening. Not only did they participate in some of the anti-racist organizing but what I thought was pretty thoughtful is the way that they took a backseat, not trying to take over the way that white parents often do with PTAs. There's some great research by Linn Posey-Maddox on that. These young people are noticing that, hey you know I want to go to the march but I'm not going to walk in the front. I'm going to be there to support my peers. And so I think that that's one example. And I think that if I look back to those children, to earlier in their lives, there was a lot of modeling of that kind of antiracist work, if you want to call it that, or just sort of listening to people of color, having, again, meaningful, equal status, relationships. Not relationships where you have all the power as the white person. But really meaningful relationships and you know among many other things.

I'm not saying that any one of the families was doing everything right. I'm not sure what that would even really mean. Certainly there are all kinds of moments where parents were undermining their efforts. But that's one concrete example of the importance of parents understanding that when your children are younger they're beginning to develop these things that, my research really documents, take hold and become an even larger part of their racial ideology or their world view. And that becomes much more difficult to change when, for example, they're in college. There's great research by some of my colleagues that look at college students and how difficult it is to get particularly white students to think differently about race. And I think that this whole topic of white racial socialization is really important to think about more clearly and to think about how modeling is part of that.

EmbraceRace: Erin, you explained more fully what's happening right a toddler brain, and how essentially these attitudes get some purchase around age three in a way that's not true at age one, let's say. And then, Maggie, you just said by college these are even more ingrained. Not that they're unchangeable, lots of us had you know scales fall from our eyes after college happily in many arenas.

Erin Winkler: That's what we college professors have to hope anyway.

Maggie Hagerman: [Laughs]

EmbraceRace: I'm wondering between age three and age … twenty-three, what can you say about how changeable we are, how persuadable we are and when? Say, here's when things really start to harden, and here is where really kids are remarkably open. Do we know anything about what's happening in the long range?

Erin Winkler: Sure. I mean I don't want to get too wonky on you and go into stages of child development and things like that but one thing I do want to say is … adults can change their implicit bias, but you have to want to do it. So I think the research that Maggie is talking about is a lot of what's difficult to change is getting students, getting adults, to want to do this so much they will commit to that. You have to be very conscious about working to change implicit bias. You have to want to do it. You have to recognize it. You have to regularly work on counter stereotypic imaging and imagining yourself as a member of a stereotyped group and all these sort of specific behaviors and it's just like any kind of change that requires a regular daily practice. We may wish to meditate every day or we may wish to exercise every day but do we do the work? And it's actually the same with changing implicit biases.

So first you have to want to do it and then you have to put in the work. So it's possible to change. I don't want anyone to feel like well my kid's thirteen so forget it, it's already ingrained. It's too late. No. It's possible for any of us to change. But why I really encourage parents of young children to start early is we're getting primed from birth with these racialized messages and they're sinking into our subconscious very early. And so we have evidence even with six-month-olds actually three-month-olds that they can categorize nonverbally by race, based on how long they gaze at new faces of the same race as their primary caregiver versus different race than their primary caregiver. So kids are categorizing.

By two we see them using race to reason about things. So in stories, why did that person do that? Maybe it was because his skin was brown? But we don't see it reflecting the prejudice or in-group bias in the same way. And then it's three-years-old where it's really really showing that sort of bias. But we're seeing the categorization and the reasoning even earlier than we're seeing that bias, that pro-white bias. One thing that changes when kids get to be around seven or eight is actually, these are experiments that are around resource distribution. So if you ask kids to decide who's going to get the toys or the new playground equipment or whatever. Five and six year olds will show in-group bias or show a pro-white bias and they'll say, "They should get it because they're white" for example. Seven or eight and nine, ten year olds in the same experiment, they will make the same biased decisions but they have now learned that you're not supposed to say, so their bias is becoming more implicit and so they will say things like, "Oh well these people should get it because they worked harder or these people should get it because they're more deserving." So we see the ideas becoming more implicit around age eight. That's why I'm really urging parents to try to, before it gets so implicit, when kids are still willing to talk about their reasoning, that's when you can really sort of help disrupt. Now you can help disrupt it later but at that point it's become a little bit more subconscious.

EmbraceRace: Right. So we should, we're getting close to wrap of time and we have so many questions! There’s a question here that relates to something you said earlier about empowerment. “Can you say more about how exactly to link empowerment when we're teaching kids about unfairness and I want to sort of unpack it a little bit more. And you know we think a lot in this work about empowerment being sort of cultural empowerment. You know lots of, maybe specifically, sort of where'd family come from? You know how did they get to where they got? A lot of great examples of people doing good and doing well where you can and getting somewhere from nowhere, you know. Resilience as a family characteristic, a community characteristic. So I think of that as sort of the empowerment stuff and having lots of images in the media and all of that and exposure, exposure, exposure. But I think parents have a hard time when they, you were telling us a bit about when people actually talk to their kids about that race. How are they talking to their kids about race, right? We do the sort of empowerment and the preparation for bias you know, as psychologists call it. But what are parents of color actually doing and what are white parents actually doing when if they talk about race, according to the research?

Erin Winkler: OK. So let me give an example of sort of pairing, appealing to kids sense of fairness but linking that with empowerment. Here in Milwaukee there's a major east/west thoroughfare called North Ave. And it starts all the way on Lake Michigan. And you can imagine the homes on Lake Michigan are very lovely and fancy and there's a big fancy shiny Whole Foods all the way on the east end of North Ave. And then if you take North Ave. west all the way out to the suburbs you drive through overwhelmingly black neighborhood that looks quite different than the sort of fancy overwhelmingly white East Side neighborhood. So I'm just going to give an example of a parent of a four-year-old driving the length of North Ave. and noticing, the child saying like, "Where's the Whole Foods for the brown people?" So sort of noticing a difference for example. So here's an example where it's important to talk to the child about, is it fair that there is access to healthy, fresh, fancy groceries where white people live and not where, in this case, where African American people live? Of course the child doesn't think that's fair. I don't think it's fair at all. But you don't just wanna say like, "Well that's how it is," right? We do want to say, sometimes our things are not fair for people of color simply because they're people of color and that's wrong. That's wrong and it's morally unjust and it's something that you know we need to all work on together. But you don't want to just leave it there for children, especially for children of color. That's going to be very disheartening to say the least. And so here is an example where it's important to pair that right up, especially for a young child, with something concrete that they can feel. Not abstract, something that they can witness and be part of.

So, for example, here in Milwaukee we have lots of urban agriculture, urban fisheries, and people who are working to say like this is an issue of racial justice. And so she can say you know, "Here's people in our community that you can meet who are working on this. And guess what? They are saying that we can come and help them water the lettuce, you know." So this is something showing kids that there is unfairness but people are working to do something about it and the two are linked.

Maybe we can link to an exercise that I call the spider web activity (find it at the end of this article) that you can do with little kids where you help explain institutional racism to them by saying that it's something that's gotten tangled up for a long time. Unfairness is really tangled up from even before mom was born and even before Grandma was born. That blow their minds. That was like ancient history to them and you can say, "You learn that Rosa Parks helped untangle some unfairness and you learn that Martin Luther King helped untangle some unfairness. Here are people in our community who are untangling unfairness and all of us have to work to untangle that unfairness because it's gotten really tangled up."

EmbraceRace:Thank you both so much. Our time is at an end. I wanted, we wanted to close though by making sure we spelled out for you the six suggestions that Erin and Maggie had for engaging with children on this topic of race and racism. We touched on many of these in the conversation. And we will share related resources, too (see below).

EmbraceRace:Maggie and Erin, thank you so much for the phenomenal work you've both done, work which is actively reshaping right this conversation about how we help our kids learn about race in a really thoughtful and constructive direction which we obviously desperately need in this country. So thank you. Thank you. Thank you for your work.

Related Resources

Here's How to Raise Race-Conscious Children

Erin's advice for engaging kids on the topic of race. Includes the Spider Activity for explaining institutional racism to young children. She didn't choose the article's title, just so you know!

by Erin Winkler for Buzzfeed

How Well-Intentioned White Families Can Perpetuate Racism

An article about Maggie Hagerman's book documenting the two years of research she did talking to and observing upper-middle-class white families in an unidentified midwestern city and its suburbs.

by Joe Pinsker for The Atlantic

And don't forget their fabulous books!

White Kids: Growing up with privilege in a racially divided America

by Margaret Hagerman for NYU Press

Learning Race, Learning Place: Shaping Racial Identities and Ideas in African American Childhoods

by Erin Winkler for Rutgers Press

Margaret A. Hagerman

Erin N. Winkler