"Yes, My Mother is Japanese. But..."

Notes on A Hyphenated and Colon-ized Identity

By Sara-Momii Roberts

Sansei, Nisei, and me, Yonsei

My neighbor was having a stoop sale this morning, and although I have been living next to this woman, her son and husband for the past two years, today was the first day that I reached out and talked with her. She is Japanese, from Japan. Her husband is from Japan. Her son was likely born in the United States but goes back every summer to Japan.

I am half-Japanese and, like an imposter, feel both attracted to and intimidated by Japanese Japanese people when I encounter them. Maybe this is why I haven’t reached out to this neighbor before?

I get self-conscious about the degree to which I am what I say I am if she doesn’t see it. I imagine this Japanese woman looking at me and wondering to herself: Japanese? She doesn’t look or sound Japanese. But, she does know something about my dishes … hmmm.

A complicated backstory…

My Japanese mother was born in San Francisco, my Japanese grandparents were born in Redwood City and San Francisco, and it was my great grandparents who came to this country from Japan in the early 1900s. To non-Japanese people I tell this story with authority. One side of my mother’s family came via the traditional immigrant path: Japanese carnation farmers. The other via a more unique route: journalists and community leaders.

If I get that far in discussing my racial background, I usually end up sharing how both families were uprooted and sent to internment camps during WWII. Sometimes I get even deeper and discuss the loss of language, starting in my mother’s generation (born after the war), a byproduct of discrimination. I want them to understand why I don’t speak Japanese.

On this morning, I browsed through my neighbors’ beautiful Japanese wares and was immediately captivated. I picked up one that could have been a handmade mini-vase or container for sake. This could be my in!

“Oh, this is beautiful.” I hesitated, not wanting to be wrong. “Is it for sake?”

“Yes!” my neighbor responded. I felt like a student making my teacher proud. I picked up another. “I love these dishes. Are these for shoyu?”

“Oh, you know what you’re talking about! Yes, for shoyu,” she responded.

Although I never learned much of the language, there are certain words I grew up saying in Japanese that still don’t feel right in English. I only say soy sauce instead of shoyu if I’m speaking to someone who needs translation. And when ordering or making teriyaki, I can’t say it with an American accent (ter-ee-ya-kee) but always use a Japanese accent (te-dee-ya-kee). Japanese speakers don’t pronounce the “r” in that word. Neither do I.

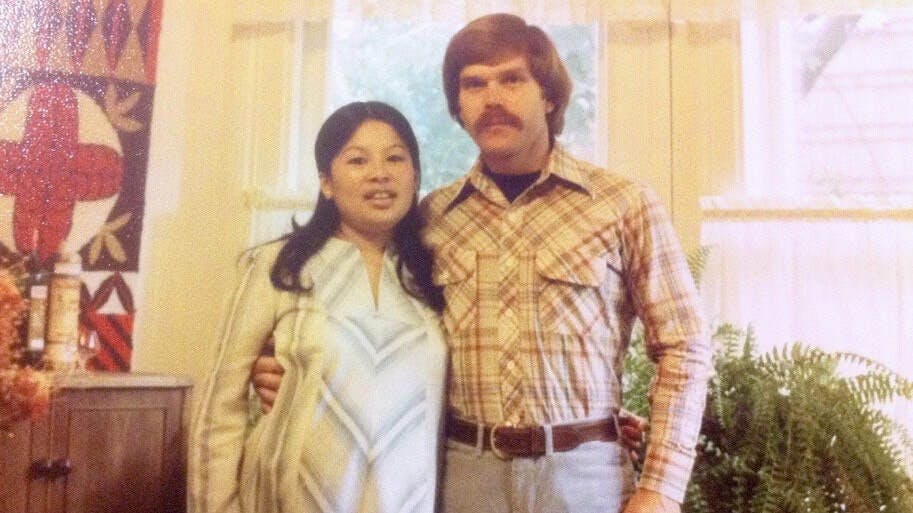

My mother, pregnant with me, and my father in 1978 in their home in Berkeley, CA.

At this point my darling husband, who was watching our boys play in the driveway near the sale, jumped in:

“Sara’s Japanese,” he explained with a big smile.

“Oh, wow. You are?” my neighbor responded, looking carefully at me.

At such moments, I get self-conscious about the degree to which I am what I say I am if she doesn’t see it. I imagine this Japanese woman looking at me and wondering to herself: Japanese? She doesn’t look or sound Japanese. But, she does know something about my dishes … hmmm.

Over the years I have practiced my response to situations when my ethnic identity comes up. Like most mixed race people, this response varies depending on who I am talking to, what the context is, where we are located, and what I perceive the other person might be interested in.

“Yes, my mother is Japanese. But she was born in San Francisco. My grandparents were born in the United States, too, and my father is white, English and Scottish.” I add the “but” because I want to make sure that she knew there was a reason that I don’t seem Japanese.

“Ohhh.” She nodded in understanding and interest, so I went on.

“I’m Yonsei.” I say this feeling confident that she knows what I’m talking about. She does.

Me at four with my baby sister, my father and his parents.

Do I encounter the world as a Japanese person? To a people historically obsessed with bloodline, blood purity and cultural propriety, maybe my particular claim is full of holes

.… and a pointed challenge

Yonsei, or fourth generation, is a label used frequently among the Japanese diaspora (North and South America) to distinguish one’s place in relation to Japan. Growing up I recall this label often being used to describe me to members of our extended family and Japanese friends. Yonsei are made up of many mixed-race people. A yonsei with two Japanese parents was a rare thing among my peers.

Issei, or first generation, describes the Japanese who emigrated between 1885 and 1924 to the United States, Hawaii and, to a lesser extent, South America. We revere the Issei as our pioneers, those who endured racism and marginalization and who, as non-citizens, suffered especially during WWII. Most Issei lost control of their families and businesses once the Japanese internment camps were established.

Nisei, the second generation, describes my grandmother and grandfather. Most Nisei were teenagers — or younger — during the camps, and are among the only group we can still gather living testimony about the experiences of Japanese Internment.

Sansei, third generation, describes my mother’s generation. Born after the war, many, like my mother, weren’t taught to speak Japanese by their Nisei parents but did grow up with strong Japanese-American cultural heritage in or near Japantowns. At the same time, they attended multiracial public schools and became “Americanized.” A large portion of Sansei out-married, mainly to whites.

“Yonsei! Oh, so it’s really like you’re American.” My neighbor responded with certainty and a smile. She was, after all, more qualified to discern, right?

When I heard her say this I smiled, nodded back, and processed. This woman was the real deal. Maybe by the time Yonsei rolled around, by the time our blood had been so differentiated, my claim to authentic “Japanese-ness” became questionable? Do I encounter the world as a Japanese person? To a people historically obsessed with bloodline, blood purity and cultural propriety, maybe my particular claim is full of holes.

My grandmother, a genki 91 year-old, represents the few, important cultural links I have to being Japanese American — Buddhist church bazaars, homemade tsukemono and New Year’s mochi. My husband is Puerto Rican, my sons are 1/4 Japanese, we live in Brooklyn and partake in various aspects of life in the city that stem from any number of ethnic groups.

This “American” needs more than a hyphen

Me, my husband and our two boys at an Oakland As game

What am I? I am a mixed-race woman with Japanese and European heritage. Over the generations I have been disconnected from the ethnic languages and traditions of my multiple heritages and have adopted aspects of the many cultures I have grown up with.

With a white father, I don’t look fully Japanese, but I don’t look white, either. Standing next to my husband, most people “read” me as Latina. I can’t confidently call myself Japanese American, fully, but I’ve never been to Europe and don’t know much about my ancestry there. Unlike my neighbor, I am not satisfied with calling myself “American.” My “American” needs a hyphen, maybe a colon too. I need to tell a nuanced story about my heritage, as will my boys, and that’s what I claim.

I chose four Udon bowls and a few rice bowls to buy from my neighbor. I still owe her money. Maybe when I go back tomorrow to pay, I’ll bring some of this up.

Sara-Momii Roberts