Encouraging Cross-Racial Friendships among Children

The challenges we face as a country and as communities around racial equity and racial inequality won’t be solved simply by increasing the number of cross-racial friendships among children (and adults, for that matter), but it certainly would help! Our guest for this Community Conversation was Professor Amber Williams who researches the why and how of cross-race friendships among kids.

In this hour long conversation, first, Professor Williams presented what she’s learned and discussed the implications for raising kids. Next, EmbraceRace Co-founders, Andrew Grant-Thomas and Melissa Giraud, facilitated the Q & A with the community. Resources are included in the edited transcript that follows.

EmbraceRace: Welcome to everyone joining this conversation live - there was a lot of interest in this topic. Thank you for sending in your questions and keep them coming. We are honored to have Professor Amber Williams with us today.

Professor Amber Williams is an assistant professor of psychology at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. Her broad research interests focus on the role of race in shaping youth self concepts, their relationships with in and out group members and their academic outcomes. Amber received her Ph.D. in psychology from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. She identifies as Black or African American.

Amber, I'll turn it over to you to start!

Professor Williams: Thank you all for taking the time to join us today! I'll be discussing the factors that influence children's engagement in cross-piece friendships and how parents and, more broadly, we as a society can encourage more cross-race friendships among children.

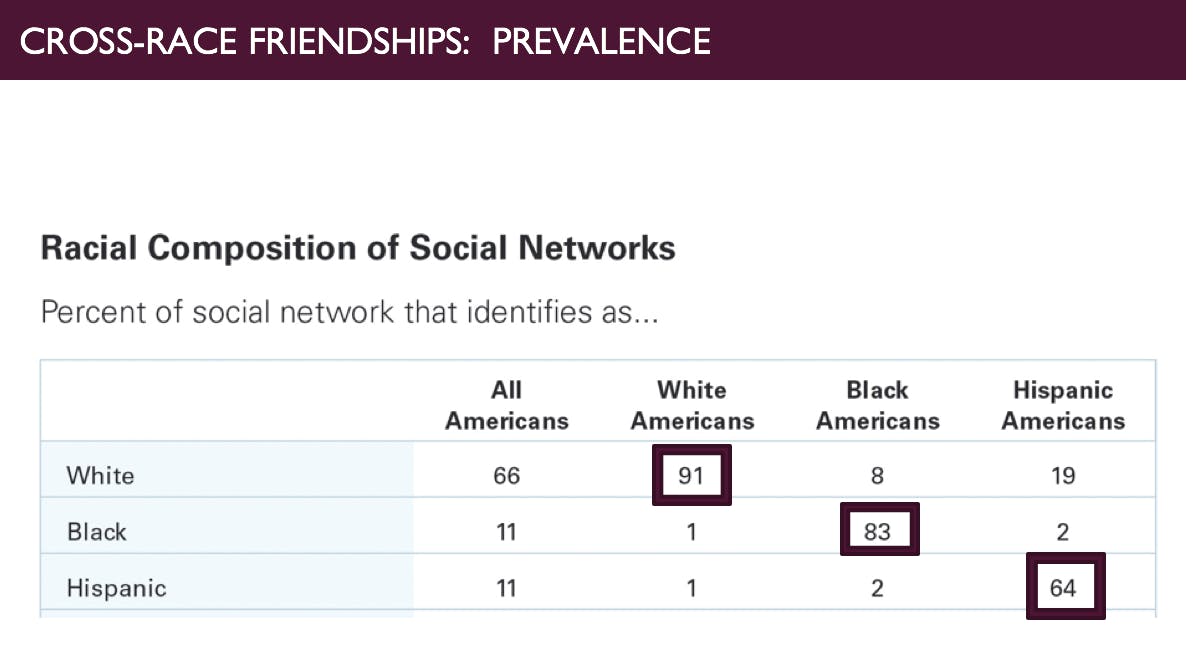

First of all, among adults, research shows that same-race friendships are more prevalent than cross-race friendships. For example, this survey conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute, they actually asked the question, name people with whom you discuss important matters. And they found that more than half of the people listed by White, Black and Hispanic individuals were people of the same race. This is likely the network these individuals consider part of their inner circle and the majority of them are the same race as they are. That’s adult friendship patterns, what about children?

Public Religion Research Institute, 2016

Professor Williams: Among children, research shows that as children age, cross-race friendships become less common and are less prevalent than same-race friendships. Additionally, a paper that I coauthored with Steven Roberts and Susan Gelman showed that Black, White and multiracial children ages 4 to 6 expect Black and White target children (children that they are looking at on a screen and making judgments about) will be friends with individuals of the same race as they are.

So children believe that people will be friends with people who are of the same race. And they are also less likely to have friends who are of a different race. What’s more, the prevalence of these cross-race friendships decreases as children transition from early to middle childhood.

Professor Williams: So why does this matter? Why should we care that people want to be friends with people of the same race as them?

Well it goes without saying that racial tensions in this country have become particularly strained. And the ways in which people think of various social issues is sharply divided along racial lines. So, for example, on the issue of racism against black people, the Pew Research Center found that 43 percent of black people believe this country will not make the changes needed to give black people equal rights to white people. Only 11 percent of white people believe this. On the other hand, 38 percent of white people believe the country has already made the changes needed to give black people the same rights as white people. And only 8 percent of black people believe this.

So race and more precisely racism is still the problem that we all live with. But it's a problem that we don't talk about. And we'rereallynot talking about it with people who are of a different racial background than we are. As demonstrated by the early graphic I showed, people are generally having these conversations with people who are the same race as they are.

Professor Williams: On the positive side, cross-race friendships have demonstrable benefits. Research among adults has found that having more cross-race friends can promote more positive racial attitudes and also lowers feelings of discomfort when in interactions with people of a different race.

With children, we know that cross-race friendships reduce feelings of vulnerability in the school context. And we also know that cross-race friendships can protect adolescents from the negative effects of school-based discrimination, from feelings of loneliness, depressive symptoms and [lack of] school belonging.

Basically, what that means is where discrimination would normally have a really negative impact on kids, like making them more lonely, when kids have cross-race friendships, they don't experience that link between discrimination they experience and being more lonely or having more depressive symptoms in the school context.

Cross-race friendships are important, but they're also rare. How do we encourage more mutually beneficial cross-racial friendships in childhood?

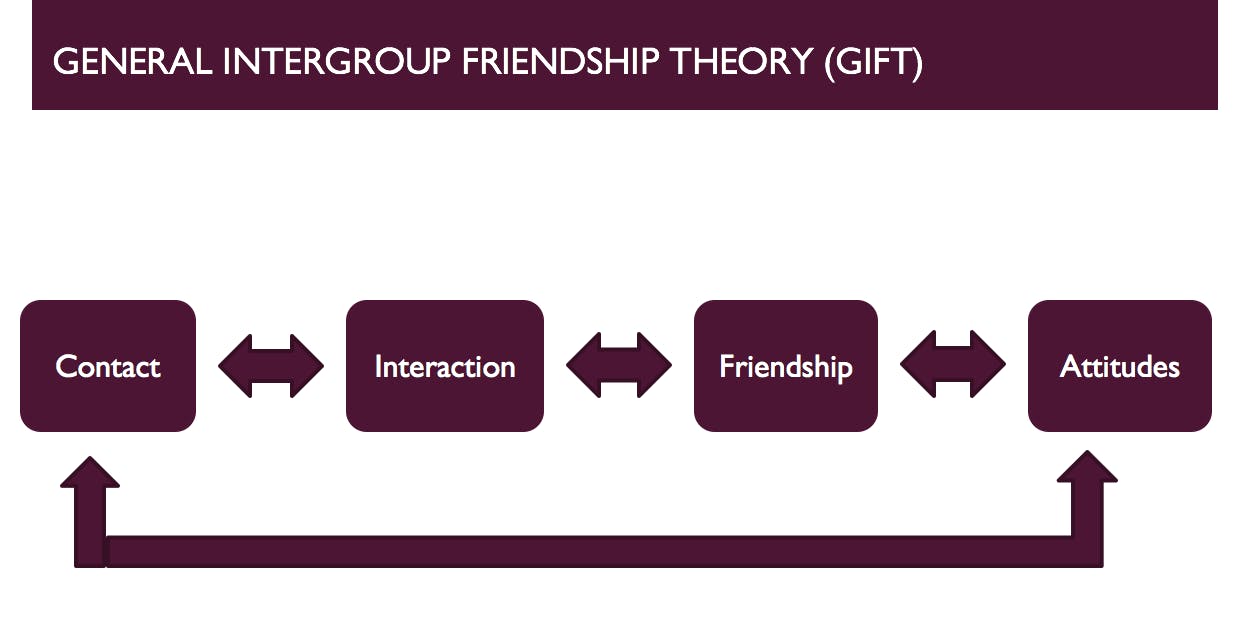

We've established that cross-race friendships are important, but that they're also rare. This begs the question: how do we encourage more mutually beneficial cross-racial friendships in childhood? So next I'm going to discuss a theory proposed by Bigler, Rohrbach and Sanchez which seeks to understand how cross-racial friendships develop and influence racial attitudes.

Bigler, R. S., Rohrbach*, J. M., & Sanchez*, K. L. (2016). Children’s intergroup relations and attitudes.

Professor Williams: In the General Intergroup Friendship Theory or GIFT, we have a model in which the success of each process depends on the preceding process and influences the one after. For example, cross-race friendships are dependent upon the success of interracial interactions, which in turn are dependent on the opportunity for and success of cross-race contact. On the other, positive cross-race friendships should promote more positive cross-race interactions, which should then promote the pursuit of more cross-race contact.

Likewise, children’s cross-race friendships may lead to improved racial attitudes, but racial attitudes should also lead to more high quality and the higher frequency of cross-race friendships. So this is a cyclical, bi-directional relationship in the way each process influences the next.

Keeping that model in mind, today I'm focusing on the ways in which children's racial attitudes may influence the development of cross-race friendships. I'm also adding an additional component to this particular topic exploring how parent behavior and attitudes may affect children's cross-race friendship development.

First, I'll discuss how children's racial attitudes relate to their race-based friendship choices. Research conducted at UT Austin by Bigler and Rohrbach found that in a sample of majority white children ages 4 to 6, those who felt more comfortable being in close proximity to black individuals also behaved more comfortably and positively in a situation where they had the opportunity to actually interact with a black person in a waiting room situation.

In another study, Aboud, Mendelson and Purdy found that white children in grades 1 through 3 as well as those in 5 through 6 who expressed higher levels of prejudice, defined by feeling more positively toward the racial in-group then towards the racial out-group, had fewer cross-race companions and lower quality cross-race friendships.

Interestingly, they did not find this link between black children's in-group and out-group feelings and the number or quality of cross-race companionship and friendship.

Finally, I'm going to discuss a study that I conducted with my colleague Rebecca Bigler at UT Austin in three majority-Hispanic schools and one majority-White school. These children were ages 5 to 11 and the majority of our sample was in fact Latino. We told them that they would be asked to participate in a pen pal program because we wanted to understand how kids develop friendships. We didn't tell them anything about race at this point because we didn't want that to affect the choices that they made.

We showed them 24 photos of kids, including four black girls, four black boys, four Latino boys, four Latino girls, four white boys and four white girls. We told them that these were all kids from another classroom in Austin. The children were asked to choose four possible pen pals to write a letter to and we told them we would try to match them with their top choice. Following the pen pal procedure, we asked children questions related to their racial attitudes, including questions assessing your attribution of positive and negative characteristics to individuals of different racial groups. So, one group is bad or one group is good. We also asked children about how happy they would be to have people of different racial groups as doctors, friends, babysitters. That proximity measure that I talked about being related to children's comfort with people of a different racial background.

We found that children who attributed more positive characteristics to black people as a whole were then more likely to seek black people to be pen pals with. So those kids chose more black people in their four pen pal choices at the beginning of our study.

The question becomes, how do we promote these attitudes in children, and how to encourage such attitudes while also encouraging cross-race friendships?

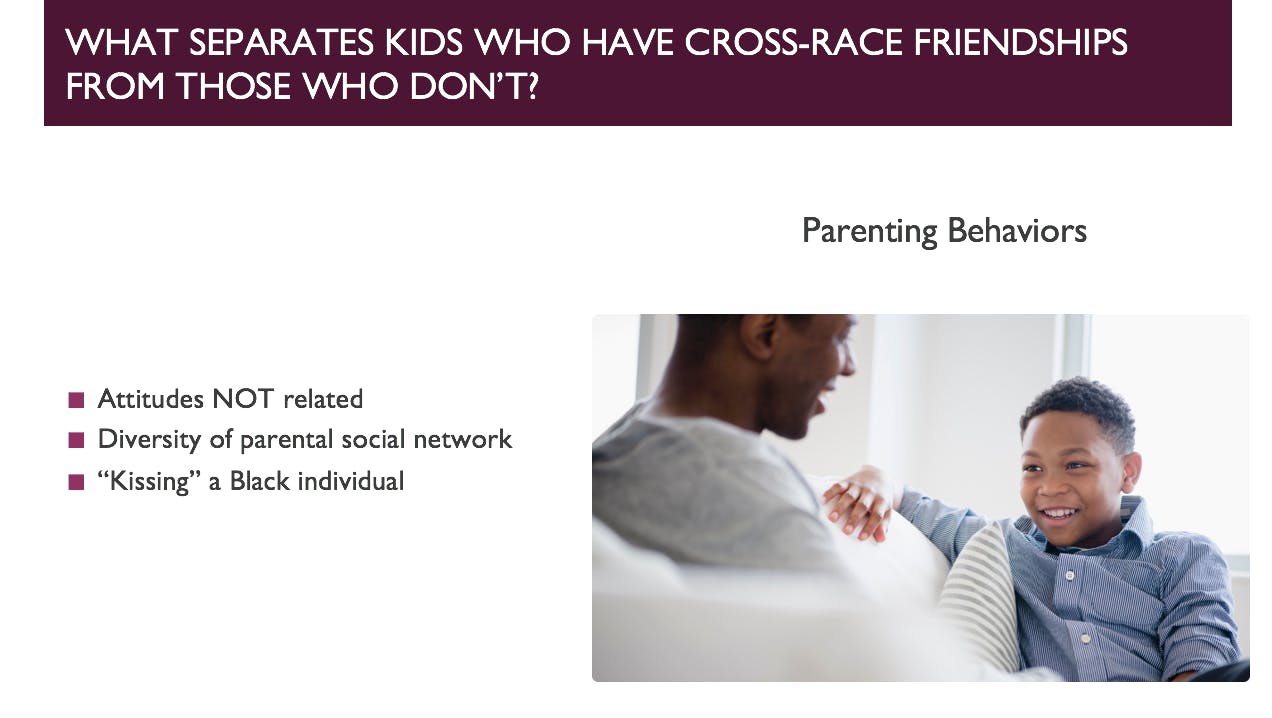

The first study I'll talk about was conducted by Paulke, Bigler and Suizzo,, they found that among white families, parents own racial attitudes did not relate to their 4- or 5-year old children's racial attitudes. And parents and children weren't very good at predicting each other's racial attitudes. They asked kids to predict their moms’ racial attitudes and they asked moms to predict their kids’, and there wasn't a lot of relationship there.

However, parents who themselves had more friends of a different racial background also had children who were less racially biased. They were less likely to attribute negative traits to out-groups or attribute positive things to in-groups. So they were basically more neutral in their attributions.

And this is important. I just noted in our study we found that when children attributed more positive traits to black people, they were more likely to pick a black pen pal. So basically, parents’ behaviors are indirectly affecting their children's behaviors through children's attitudes.

In another study, Rohrbach and Bigler found similar results, which showed that parents’ attitudes did not predict children's attitudes. However, the number of black individuals in parents' social networks did predict their children's proximity rating - their happiness with having a black person as a doctor or a friend or something like that. Again, this is important because in the same proximity study, children's proximity ratings were related to their treatment of a black person in a waiting room situation.

And finally, in the study that I did at UT, parents took a survey and we explored the ways in which their own racial attitudes predicted their children's. Interestingly, we found a correlation in which parents whose children had seen them kiss a black person had children who felt happier having a black person in close proximity. We didn't find this correlation with white or Latino proximity ratings, which I find really interesting.

To recap, cross-race friendships among parents and kids are rare. But cross-race friendships are beneficial to white kids and kids of color. How do we increase their prevalence in childhood when such friendships may be most effective in promoting racial attitudes?

We also found that children who have more cross-race friends have more positive racial attitudes, they feel more positively towards black people - and we can think about how this might be extrapolated to other groups as well - and they have parents who have intimate relationships with people of a different racial background.

"Parents' reported beliefs are not having a huge impact on their children's attitudes. But they're modeling - what their children are seeing – is having an effect on their attitudes. Those attitudes then lead them to have more positive relationships with people of different racial backgrounds, and leads them to pursue those relationships as well."

Professor Amber Williams

Again, I think what this really demonstrates is that parents' reported beliefs are not having a huge impact on their children's attitudes. But they're modeling - what their children are seeing – is having an effect on their attitudes, and those attitudes then lead them to have more positive relationships with people of different racial backgrounds, and leads them to pursue those relationships as well.

EmbraceRace: This might be a good moment to take a break and take a couple questions before we get to your talk about what we do about it.

So here’s a question which comes out of the research findings that you offered, Amber, which is, it sounds like what kids see is more important than what adults may say to children. I mean, is that right, that talking to kids matters much, much less than what they see, or is there some sort of complicated relationship between the two?

Professor Williams: So just to really recap. I want to answer your question as it relates to the study I spoke of earlier where we're finding that how parents treat black people, whether parents are in friendships with black people, has a particular effect on how kids think about black people, which then leads them to want to or not want to be friends with black people. If your child has seen you kiss a black person - whether familial or romantic or friendly - if your child has seen you do that, they feel more comfortable, they report feeling happier having a black person as their potential doctor, their potential next door neighbor. So it's proximity, they're happy to have a black person in proximity to them.

I think the work I'm presenting here shows more how parents are thinking. And we see this a lot with white parents but parents of color are also dealing with this. Parents don't want to talk about race because they feel that could make their kids racist. They feel like, if I'm not racist my kids are not going to be racist.

And so we're really measuring these attitudes, these beliefs - not necessarily what they're saying to their kids, but what they're thinking. What we found is that children are not knowing what their parents are thinking, and parents are not knowing what their kids are thinking.

"What we found is that children are not knowing what their parents are thinking, and parents are not knowing what their kids are thinking. That doesn't necessarily mean that talking to your kids is not effective, I think it's just not happening and people are assuming that they're transmitting their attitudes - I don't know how they would transmit their attitudes! I think it's a well-meaning assumption, but in the face of a society that is so race-conscious and racist in many ways, kids are getting these answers elsewhere if they're not talking to their parents. And if they see that their parents don't have friends of a different race they assume, well, we're not friends with those people."

Professor Amber Williams

That doesn't necessarily mean that talking to your kids is not effective, I think it's just not happening and people are assuming that they're transmitting their attitudes - I don't know how they would transmit their attitudes! But I think there's an assumption that, if I don't say anything ... And I think it's a well-meaning assumption, but in the face of a society that is so race-conscious and racist in many ways, kids are getting these answers elsewhere if they're not talking to their parents. And if they see that their parents don't have friends of a different race they assume, well, we're not friends with those people.EmbraceRace: There’s a follow up question to that, then I promise I'll let you finish your presentation! You said that you had some ideas about why kissing a black person had an effect if kids saw it as opposed to other races that didn't have an effect …?

Amber: My feeling about that is ... anti-blackness in this society is particularly salient. That is not to say that kids are not hearing messages about Latino or Spanish kids. It's just, when I talk to the kids I notice that they don't know what those terms are. I have to explain what those terms mean. When kids think about Latinos and Hispanics, they're really thinking about people who are Mexican, particularly where we were, in south Texas. For them, they are Latino but they don't really identify that way. They identify as Mexican or El Salvadorian or Honduran. There's a disconnect because they're not thinking about Latino as a group of people. They're thinking of it in terms of nationality and language.

But blackness in this country is very salient for all kids. And we heard this from kids when we asked them questions and they would say, yeah, my parents said I couldn't be friends with a black person or black people are discriminated against, or, my family doesn't like black people. We heard a lot of that. So I think that it's a particularly powerful idea in society given the history of the U.S. and given what's going on currently. So I think it's particularly helpful for kids to see their parent embrace a group that is not particularly embraced by the society at large and so I think that's having a particular connection with them.

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Amber. I just want to note to everyone listening and watching that the big takeaway is, if you want to be right by your kids, you should kiss me?

Professor Williams: Ha! What I recommend instead of kissing the first black person you see is …

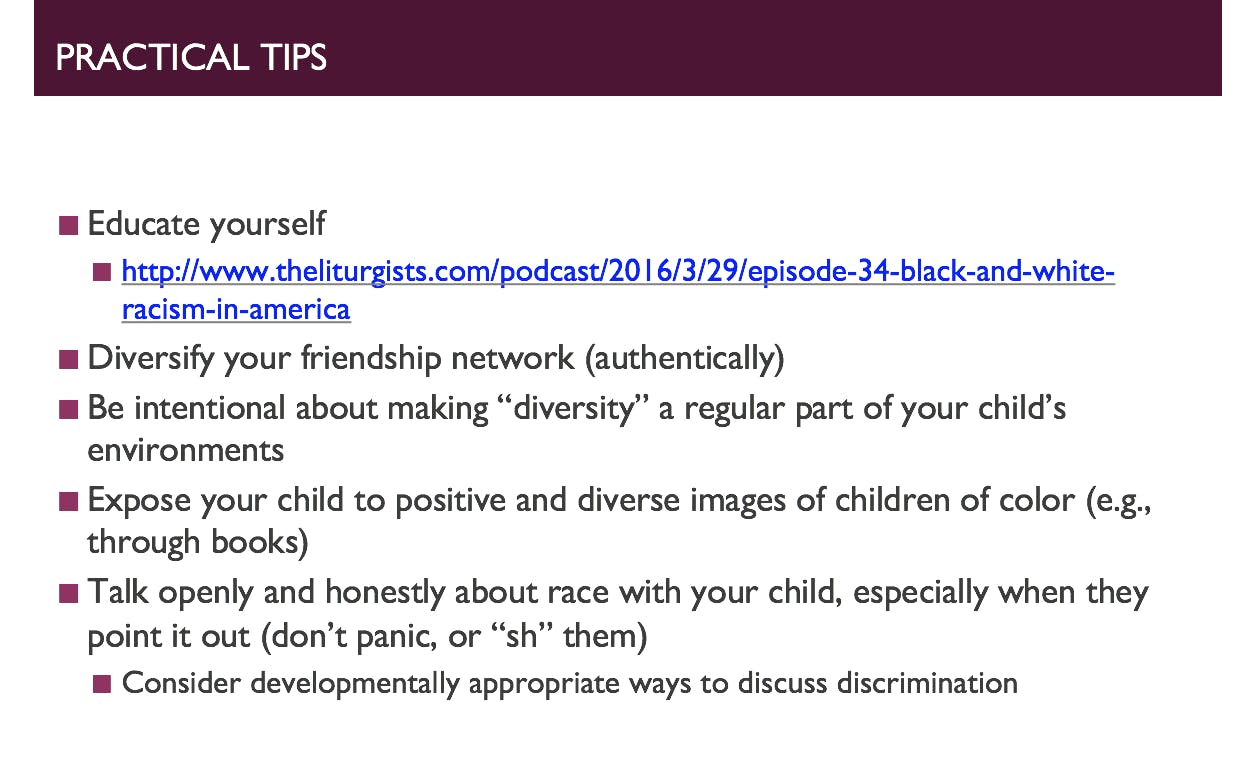

1) The first tip is ... educate yourself!

Making sure that you are able to knowledgeably and authentically build relationships with a deeper knowledge of the social and historical factors that make such relationships difficult, will make you and your child better able to engage in meaningful, affirming friendships with people of a different race.

And for white parents I think this means being aware of the ways in which such friendships can be burdensome for children of color if they involve a lot of education of white children around issues of race and privilege. So for you this can involve educating yourself on those issues so that you can provide developmentally appropriate information about current and historical racism and discrimination to your child. And this way, when your child has questions, they can feel comfortable coming to you if they have concerns or issues.

And for people to color, this also means being aware of the different privileges and concerns that your child brings to the table. So this could include anti-blackness and colorism or issues of documentation. Knowing about the issues can help you talk to your child about the struggles and concerns they may be facing, about accepting and affirming themselves as well as others

So there are a lot of issues to consider when encouraging cross-race friendships for you and your child and being educated about the different concerns and how to discuss them with your kids can be particularly helpful in addressing these issues.

I suggest starting with this excellent podcast by The Liturgists. It does focus on black/white relations in the U.S. but there's a lot of ways in which you could expand this to the experience of all people of color and in struggling to have this kind of feeling of acceptance in a world that devalues you in some ways. And it is a podcast that focuses on Christianity, but even if you're from a different religious background or not religious at all, I feel it's an important podcast and a great part to start. And at the link there are suggested readings by bell hooks and other activists which can be a starting point for thinking about race in America more broadly.

I also wanted to provide some suggested reading. And these are some good books that I would personally start with. I'm currently reading the Antibias Education in Early Childhood Classrooms book. It is geared toward education and teachers but having read it, I think it is very applicable for parents in thinking about ways to address issues of racial bias when they come up, what happens when your child says something that is racist or toward another group. How do you address it, and how do you incorporate anti-bias and multiculturalism in the home as well as in the classrooms. So I think it's really a good book and it focuses not just on race and also talks about family diversity and economic status and other issues that children come to you when they are in the classroom.

And Beverly Daniels Tatum’s Why are all the black kids sitting together in the cafeteria? is a really easy to read and very engaging book. She talks about socialization techniques you can use at different stages, for example, she talks specifically about discussing slavery with really young children who may be concerned about their safety after learning about it. And so it really provides information on how to address such issues in ways that are developmentally appropriate.

I'd also recommend Ta-nehisi Coates' Between the World and Me - it's written as a letter from Coates to his son and talks about the struggles of being a black man in America.

And finally, We, Too, Sing America is a review of the discrimination faced especially Southeast Asian, Muslim and Sikh individuals. But it also talks about issues of documentation, Black lives Matter and so basically it talks about those issues and gives you a history of those movement's involvement in it and how those really exemplify the American experience.

2) Diversify your friendship network.

So much of the work that has been conducted on parents' influence on children's racial attitudes finds that there is no relationship between how parents THINK their children feel and how they feel about race and how their children think their parents feel and they feel about race. Parents' behaviors - what they do, mainly the diversity of their friendship networks - has been shown to have a positive influence on children. And so children are observing what their parents model.

3) Along with this, diversifying your child's environment is also really important.

So making sure that your child has plenty of opportunity for cross-race contact is an important aspect of getting used to and more knowledgeable about the lives of people who don't look like them.

So, you may be asking, how do I do this? Segregation is the norm in the U.S. and this makes cross-race contact really difficult. And my answer to that is, yeah, it is difficult and you have to be really intentional. You have to go outside of your neighborhood and perhaps go to your local boys and girls club. Boys and girls club is an organization I've worked with in my research and it's a very diverse organization and I think it'd be a great organization if you want to enroll your child in after school program.

One caveat I would say is, be careful about asserting yourself in spaces that are meant solely for people of color or for those particular communities. And be careful not to exoticize communities and their spaces. And so you could bring your children to another park outside of your regular community. After school programs that serve diverse children or even community-based language learning. Those may be a good place to start doing that research.

There's no easy answer to know what spaces might be the most appropriate. Some of this is trial and error. I would say feel free to ask community members or liaisons. I think we're not direct enough when it comes to race, we're constantly speaking in code. So asking if it's appropriate for me to be in this space or is this is a space for people in the community. Don't let the fear of making a paralyze you. If you make a mistake, apologize and commit to do better. That's really all any of us can do.

Additionally, being knowledgeable of and supporting school integration initiatives in your district is really important. Know what's going on with the schools. Know what's going on with the busing. Any organizations that are trying to improve the quality of public schooling particularly for kids who are low-income and kids of color. Become involved in your local politics. Know the issues around districting and gentrification and advocate for affordable, integrated schools.

There's a saying that all politics is local. And after the election, when I was in Texas, I became really involved in local politics and it was such a learning experience for me - there's so much going on. Becoming aware of those issues and fighting for the right to quality education for all students is really important for the more structural, long-term goals.

So while you're doing that - fighting the good fight!

Another way to diversify your child's understanding of the world? I live in San Louis Obispo from which I have to drive two hours to find a majority black community. So sometimes it's just not feasible to regularly expose your child to different groups of people, whatever that group might be, given your location.

4) That's where media and books come in and an effort to expose your child to people who are look different from them.

Books that focus on children of color often make references to historical discrimination and hardships faced by people of color. And there's nothing wrong with that. But it's also important to have books that portray diverse children normatively living their lives. Exposure to children who look different but have the same joys and struggles and concerns and happiness as other families allows your child to see both the differences and the commonalities that they have with other children and that's really important.

And this means also thinking critically about the media that you allow your child to consume. One challenge that you can take next time your child's watching TV is, look at the characters. Are there any characters of color present? Is the person of color always a sidekick? Are any of the protagonists, the main characters, people of color? Are dark-skinned people always portrayed as villains? I think we underestimate the extent to which children are really internalizing these images. Try to see these moments as opportunities for discussion and also opportunities to steer children toward shows that portray children of color in positive ways. [Book suggestions follow.]

5) And finally it's important that children feel comfortable talking to their parents about questions they have about race.

If they feel comfortable discussing these things with you, then you'll have the opportunity to shape their attitudes in ways that promote egalitarianism and equity. Often when kids talk about race, especially in public, parents shush their kids or tell them to be quiet or talk in really hushed tones. This sends a very powerful message to kids, that talking about race is bad and just talking about race makes someone racist.Dr. Kristin Pauker conducted a study where she had children come in and play the "guess who?" game. I'm sure many of you have seen this, where you have to guess who the person is [from a visual] and so you ask questions like, does the person have a hat on? Does he have glasses?

Dr. Pauker basically varied the individuals by race, clothing color and gender. And kids readily eliminated the choices based on clothing color and gender. However, when it came down to narrowing the options between, for example, a white man and a black man, children would not ask about his race even if it meant losing the game. And I've seen the videos of this and they're kind of hilarious in a very sad way, where kids are basically staring at a card and it's just so obvious but they just will not say it. And in one case, a dad had been there for a while trying to figure out how to say it without saying it just said, "Is the person black or white?" And the kid looks at his dad says, "You're racist!" Kids are really getting the message that just talking about race is a racist thing.

Similarly, in my own work, I've interviewed kids where we sorted photos by race and ask kids to guess how we sorted them. And I have children saying, I know the answer but I can't say. And I said, it's OK, you can tell me. And they refused to say. I ended up having to tell them I sorted them by race. And their response: "That's what I was going to say. I just didn't think we could say that.”

Kids are really getting this message and I think it's really problematic because, if you're not talking to your kids about these issues, someone else is. And whether it's more subtle messages that they're getting in the media, more explicit messages they're getting at school through peers. Those messages can really internalize negatively for your kids even in the way they think about others and the way they think about themselves. Open and honest communication with kids on these issues is very important. Because, again, that allows you to shape their attitudes in ways that are promoting of equity and egalitarianism.

I do quickly want to thank Dr. Rebecca Bigler who was my post-doc advisor counseling me on this work, Chantal Ramirez, who was a grad student at UT, the NSF who funded the work that I did, and EmbraceRace and Andrew and Melissa for having me. I'm really honored to be here.

EmbraceRace Community Q&A

EmbraceRace: Thank you so much Amber! We've got lots of questions in the chat and questions sent to us earlier, so let’s dive in.

A mother, Jennifer, has a 4-year old who is multiracial - Salvadorian Taiwanese - and she has a pretty diverse friend group at the moment. But she's wondering how and when these friendships will start to dissipate due to racial and cultural differences. She adds that she herself personally experienced this tension in kindergarten. She's wondering if she should engage the parents, those of these kids that her child is friends with, in intentional talks about the value of cross-racial friendships?

Professor Williams: She's wondering when those friendships start to fall off basically and what she can do. It starts somewhere in late elementary school. The study I referenced earlier showed a difference between children in grades one through three than children in grades five through six.

And I think she looked at that continuously so I can't say where the cutoff was. But I would guess about 5th grade, older elementary school. This is the point where they really start to understand race. Interestingly, as they get older, not only are they reducing the number of cross-race friends they have, but they're also starting to report less biased attitudes even as their implicit attitudes stay the same. In other words, they're starting to know it's not culturally appropriate for me to be racist. I'm still acting in these ways that I don't think are racist but that are separating me from people who don't look like me.

And in terms of what to do about that, the way we think about raising children in developmental psychology is to use a lot of positive reinforcement. My advisor, Dr. Bigler, often says parents are not explicit enough. Saying "I'm glad that you have friends who are diverse - friends that look like you and friends that don't look like you - I really like that."

And so positive reinforcement is helpful. In terms of what the other kids are doing, if you feel comfortable enough, I think it's good to talk to the parents about this, talk to the teachers about this. I think more schools are becoming aware of issues of diversity in their school. Many are concerned but a lot of them don't have the tools and don't know what to do about it. Even if you implement a book circle with some of these parents and say, hey, let's read this anti-bias education book. People are starting to understand how important these issues are particularly in the political situation we find yourselves in. So people may be more open to having this conversation and to thinking about ways to encourage those attitudes in their kids.

EmbraceRace: Thanks Amber. Here are a couple related questions folks on this call are asking. First, if you live in a racially isolated community or school, how do you promote friendships with kids who are not part of that majority community? And then the other one is, how do you promote authentic friendships? And if in your answer you could talk about the burden you've referred to of these friendships for kids of color and all people of color?

Professor Williams: It's really difficult when you live in a very isolated town. But you can be intentional about the types of places you travel to when you leave your neighborhood. So one of the questions to ask is, how much do you value diversity? How do you value it [relative to other neighborhood features]?

I do not have a child, but one of my biggest concerns moving [to take a job at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo] was when I do end up parenting, I am concerned about having kids who don't see themselves reflected in the city that I live in. And one of the things that I would definitely do is travel to L.A. and San Francisco as often as possible! And I know that's not feasible for all parents. Making sure that when you do have opportunities to travel that you're providing your children with an enriched experience, particularly if there is no one who looks like them.

Because then there's the danger of not being friends with people who look like them. But also, if they don't see themselves reflected in the world, that can really affect how they feel about themselves. You have to go out of your way but sometimes it's worth it to expose your child to different people and cultures. In those cases where you can't do that, media is really effective. There are also pen pal program that intentionally connect kids of different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

As for the burden on children of color, that's something I think about a lot because a lot of the work that is currently available is focusing on making white kids less racist. That's just the way people think about cross-race friendships and that is really unfortunate. As somebody who, I grew up in a very diverse neighborhood but I went to a school that was majority white. It felt isolating at times. People would make jokes and things like that. I knew something was wrong but I wasn't sure what. It really led to my research today. So I really identified with that question.

And I think the important thing is, again, talking to your child, not only about themselves and making sure that they know there's nothing wrong with them, that you have a strong history. So there's some research about racial socialization with young children and it shows that with black kids who are racially socialized to feel positively about themselves see images of themselves in the home - they see Afro-centric artifacts - they actually do better in reading, they're actually doing better cognitively in school.

Making sure that you're racially socializing your child of color to have racial pride and to feel good about themselves as kids of color is really important and has a really good impact on them. And in terms of their friendships, letting them know that it is not their job to educate people. For me, at the intersection of being black and being a woman, I'm always feeling bad for other people and I spend a lot of time educating others and it's draining. And I thought to myself, literally this weekend, I'm going to tell my child that their sanity is more important than other people's discomfort. You don't have to give of yourself constantly in friendships that are not beneficial to you. And so making sure that your child knows that they don't have to be anyone's primary educator.

On the other hand, if you're a white parent concerned about tokenizing kids of color, educating your child on those issues is really important, and when it comes to how do you authentically make friendships, it's really not like you have to jump through a lot of hoops. Think about, when you're friends with someone, someone you love dearly, how did that friendship develop? You know, you don't want to have people asking, oh, what are you? Where are you from? Where are you really from? Picking at your life like you're a zoo animal. You want to be treated as human. There are friends I have that I didn't know their racial background for months because I didn't need to know that first, I wanted to get to know them as a human being.

And so building that trust, just letting people know you're there. I think inviting kids to things is great, even if they're not coming, I want to be invited to things even if I don't go! That makes kids feel included regardless of their racial background. I don't think there's anything wrong with continually inviting someone. Just really going by the Golden Rule, and treating people as you want to be treated.

EmbraceRace: So many questions and not much time. A parent says her son who is a child of color has drifted away from the white friends he had in elementary school. He's now in middle school. Should she ask him about it? Should she worry about that if his group of current friends is color diverse [non-white diverse]? Is that something to worry about for a child of color?

Professor Williams: I would ask, but not in a way that is accusatory. More like, I noticed this, did something happen or how do you feel? I went to a PWI, predominantly white institution, for undergrad. I had had a lot of white friends before that, I'd been in majority white settings. And I literally went into college with the attitude, I want to be friends with everybody, I'm not just the black person. And in my attempt to do that, I felt completely ignored. It was like I wasn't there in so many ways. I would be in multiple situations where I felt invisible, people would say racist things to me. I had a roommate who said a lot of racist things to me. It was exhausting. It was an exhausting experience.

That's when I started going to a Black Students Association meetings and it was such a wonderful experience. I don't think that it made me less race-conscious. But in a world in which some kids are not educated on these issues, being around people like you can be a solace. And so talking to your son about that, you might discover that your child just doesn't feel like he fits in with white people. And at that point, I hesitate to put the burden on kids of color to reach out to white people who are not making them feel good.

I think just telling them to be open to people that are authentic and are trying and are educated in these issues is important. But not forcing them to be friends with kids who might not value them.

And I think that's why the research focuses on white kids in some ways because the burden has continuously been on kids of color and people of color to be more open. Whereas now it's shifting to, well how can we make white kids more understanding these issues, too? And so I think that's why the focus is there. But I would ask. It's always a good thing to make sure your child knows that, especially in adolescence, when they're definitely noticing these things, they can talk to you about whatever's going on.

EmbraceRace:We need to stop here. But we're very thankful to have had Amber on and for all of your questions and community and all of your answers, as well, in the chat. Professor Amber Williams - Amber thank you so much! Thanks to everyone who participated. Until next time!

Amber Williams