Who Gets to be the Hero?

By Taliah Mirmalek

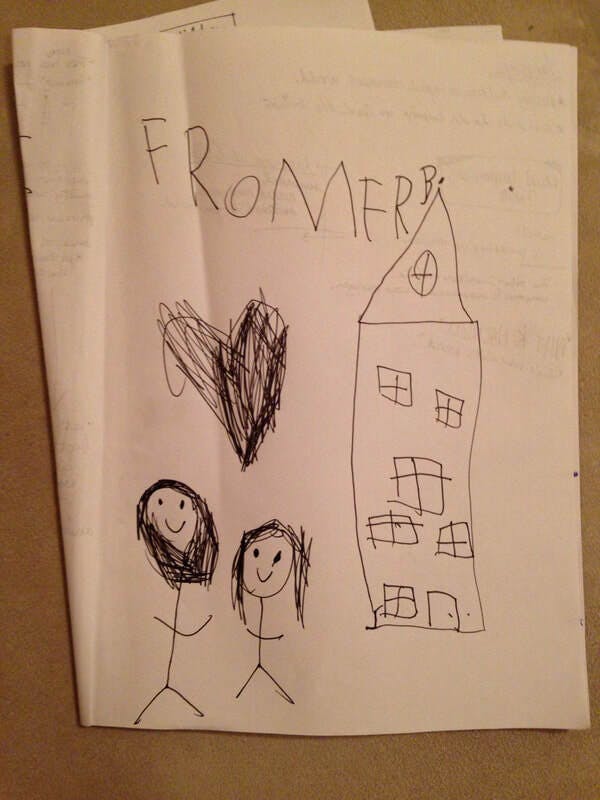

“From FRB.” Fatimah drew a smiling picture of us — me (on the left, wearing hijab) and her (on the right). According to Fatimah, the house has six windows, not seven, because the attic window doesn’t count.

Five year-old Fatimah pulled a yellow book from the shelf of Philz Coffee’s mini-library. She flipped through its pages and put it back. “No pictures,” she explained.

“What kinds of pictures do you like?” I asked.

“Smiling pictures, not angry,” she said. I pulled out a magazine from underneath a stack of books.

“That’s not a book, that’s a magazine!” She rejected my compromise as she pulled out yet another book. It, too, was rejected. “Nooo, this has no pictures!”

If we learn one thing from Fatimah’s insistent search for a book with pictures, let it be this: visuals matter.

“What we put on TV can change how kids see the world, and that is a responsibility that I take very seriously. By showcasing different role models and different kinds of families, we can positively influence sociological dynamics for the next 20 years.”

Gary Marsh, President and Chief Creative Officer of Disney Channels Worldwide.

At the same time that he describes the theory underpinning Disney’s movie and TV production strategy, Gary Marsh, himself a father, puts into words what many parents already understand: what children see — the images, pictures, movies, and toys they interact with — shape how they understand the world. That understanding is likely to stay with them well into their adult years.

When a literary racial divide reinforces the structural one

When parents decide to turn on TV, Netflix, Hulu, or read aloud children’s books from the local library, it is often to support children’s development and social skills through storytelling.

However, given the makeup of the stories’ characters, this decision often results in children being exposed primarily to white protagonists, and most often to white male protagonists. As Mia Birdsong reminds us, we must pay attention to gender, as well as race. “Kids are much more likely to hear about cismen…and not as much about the women and trans folks who have always been as critical in making change happen."

The frequently disproportionate exposure to white male protagonists in children’s books doesn’t happen in a social vacuum. Children sleep, eat, attend school, and play in communities that have been largely defined by race, racial discrimination, and the valuation of whiteness over other racial identities. Race dramatically shapes their, and our, networks of neighbors, peers, and playmates.

In one neighborhood, white flight creates white suburbia — in stark demographic contrast to the city that helps define it. In the inner-city, redlining creates impoverished black and brown neighborhoods, where low property values disenfranchise the children who attend local public schools. In some of those same neighborhoods, gentrification is now displacing the urban poor with richer, whiter counterparts, which explains all the new neighbors.

This racial divide is structural, but with the help of literary illustrations it can become embedded in our children’s psyches. When your child of color only sees white role models, white male super heroes, white doctors, white scientists, white adventurists, white poets, white artists, or white explorers, she might be unable to see herself or any other non-white person as a hero, leader, or winner. Worse, she might come to see nonwhites as the bit players or, even worse, the “bad guys” in real-life stories.

The same is true if your child is white. Moreover, for a white child, exposure to predominantly or exclusively white lead characters may lead to lack of empathy for nonwhite people. In turn, a decrease in empathy may mean an increased capacity to criminalize and support policies harmful to people of color. When your child is a person of color, this decrease in empathy may also take the form of self-hate.

“I want my daughter’s first doll and her other realistic-looking toys to not all be white, so she grows up knowing every color is beautiful…Society teaches us that white is the most beautiful, but I want my daughter to know that beauty is not specific to one color.”

Razieh, a mother

A young Muslim mother, Razieh, is raising her only child, a biracial 2-year-old daughter (part Iranian, part Scandinavian), with a few baby dolls as playmates. Visiting her home, I picked up one of her daughter’s dolls.

The doll’s deep-brown complexion stood out to me. It was different from the “classic” white, rosy-cheeked baby dolls I‘m so used to seeing in children’s play spaces.

Source: Razieh

Razieh explained the logic behind her method, saying, “I want my daughter’s first doll and her other realistic-looking toys to not all be white, so she grows up knowing every color is beautiful.”

She continues: “Society teaches us that white is the most beautiful, but I want my daughter to know that beauty is not specific to one color.”Anyone who’s ever played make-believe games with young children knows that their dolls, toys, and stuffed animals are central characters (sidekicks, villains, best friends) in their adventures.

The doll decision was also driven by a desire to help change society. “I want people in my community to know that dolls like this exist, and to help encourage them to combat the racist practice of valuing white skin more than other colors,” said Razieh.

The type of exposure matters. For Ian, the storybook’s casual, uncritical depiction of a racist class division were unacceptable. Ian and Fatimah had a conversation about it and decided not to read the Princess Latifa storybook.

Ian, a father.

Ian Belcher is a white Muslim and Fatimah’s father. Fatimah is a biracial — half-white, half-desi. He believes that exposing his daughter to people who do and don’t look like her is important. According to Ian, such exposure will help Fatimah “empathize both with people who look like her, and beyond, including the diverse people who make up her Muslim community.”

However, for Ian, the mere inclusion of characters of color among the toys, books, shows, or movies Fatimah engages is not enough. How characters are included is a crucial concern.

This past fall, Ian’s daughter Fatimah celebrated her 5th birthday. A family friend gifted her a storybook about the adventures of Princess Latifa.

Source: Ian

At first glance, the fact that the book’s protagonist is a Muslim woman is exciting for many Muslims, who can rarely find storybooks with any Muslim women at all. Each storybook in the series has a Muslim princess protagonist who wears a headscarf.

Upon opening the storybook, Ian noticed that the princess of the story was white and rosy-cheeked, while the rest of the characters followed a color gradient. Princess Latifa’s friends were all shades of brown, and the maid had the darkest skin color.

He checked the back of the book.

All of the princesses in the series were similarly light-skinned. The only exception was Princess Rasheeda, but even her brown complexion contrasts sharply with the white complexion of the other main character, the Prince.

The type of exposure matters. For Ian, the storybook’s casual, uncritical depiction of a racist class division was unacceptable. Ian and Fatimah had a conversation about it and decided not to read the Princess Latifa storybook.

By not reading storybooks that reproduce racist tropes and color-coded social structures, Ian believes he’s giving Fatimah an advantage. He thinks his own upbringing, where he was exposed to African Americans on Cosby, Family Matters, and so on, shaped his ability to empathize with the diverse Muslim community he joined as a convert.

By exposing his daughter to alternative, social justice-oriented visions of society, Ian says that “Fatimah has the advantage of being able to both witness the world around her and imagine how things could be different.”

Another world is possible

Gary Marsh works for Disney, one of the world’s largest international media corporations. A study by Colorado State University professors found that “gender, racial, and cultural stereotypes have persisted over time in Disney films.” Moreover, “marginalized groups were portrayed negatively, rarely, or not at all.” In other words, don’t look to Disney for solutions.

The onus is on us to seek out the visual culture we believe will support our children to continue the work of building community, starting with our own families, according to anti-racist, anti-colonial, social justice principles. When we only select books with white main characters, we are effectively choosing not to select books with non-white main characters. This is not an “innocent” choice.

Inspired by the decision to incorporate social justice in our relationships with children, imagine now an alternative ending to the opening scene of this story. “That’s not a book, that’s a magazine,” she said, rejecting my compromise as she pulled out yet another book.

She flipped through the pages to find colorful illustrations of teams of girls — Latinas, Arab American girls, girls in hijab, Asian Americans, African Americans, multiracial girls — on adventures, saving the day. I got to spend my Sunday afternoon building Fatimah’s imagination, reading the story aloud to her, awesome illustrations and all.

Taliah Mirmalek