When the Racist is Someone You Know and Love...

By Katherine Fugate

*Trigger warning: This piece includes accounts of racist and sexist slurs.

“Don’t worry, pretty lady. I’ll make sure to use a good, strong lock to keep the niggers out.”

He smiled. I blinked. Fifteen years ago, I was moving into my third-floor condo in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana. I’d hired a neighborhood locksmith to re-key the locks. The place was the size of a postage stamp but it was all mine and it had an extraordinary view. Below me was a lush courtyard where weddings took place. If I stood on my tiptoes, carefully leaned over the wooden dish rack with mismatched dishes and looked out my tiny kitchen window, I could see the Mississippi River.

As the locksmith worked in the open doorway, the trilling chords of the calliope from a steamboat clung to the cold river air and crossed the threshold, drifting inside, chilling the room.The word had been given no special weight among the rest. The man’s eyes kind. His skin white, his belly thick, his hands bruised and scarred. He was missing a finger. He reached into his worn leather bag and withdrew a heavy deadbolt. Bigger than the one I had.

I’m white. A woman. Five-foot-two and blonde. He was white. A man. He didn’t want to just re-key the locks I had. He wanted me to feel safe.

I let it slide. I let him believe it was safe to speak to me that way.

When I turned 13 years old, I learned the “other” is not always on the outside of the door. It was summer. A pool party. Bathing suits, pimples and braces. I was a brand new teenager and he was a brand new stepfather. Even though it was my birthday, the charismatic stepfather was the center of attention. Women on the block were drawn to him. He was big, strong, virile. Men liked his sense of humor, bold and crass. He held the room in his hands.

He liked to drink. He sang the loudest as I blew out the candles on my birthday cake. He drank some more. Then my new stepfather pulled my mother onto his lap. It was easy for him to do. She was small, blonde, like me. He put his large hand over her vagina, twisting her bathing suit bottoms in his hand, wriggling for the right fit, like fingers in a bowling ball.

He told the men in Bermuda shorts and sandals, “See this? This is my cunt — You boys stay away from it.”

An uncomfortable silence. Was it from his actions, the word he used — or both? Then he laughed heartily, breaking the spell.

I looked at my mother. She wouldn’t look at me. She looked down, at her bare feet, and stayed very still. My mother was 31 years old. This was her third marriage. She had three children. She didn’t have a job. So, she let it slide. And picked up a glass of wine.

When I was 15, my stepfather took me on a road trip. I was the oldest child and something had to give. He was a truck driver. Cocooned inside the top of his cab, I watched the world go by as we passed tall green trees and crossed state lines. He knew the names of all the waitresses at truck stops. And they knew mine. Oh, does he brag about you. Shows us pictures of all you kids. He bought me every tacky souvenir I wanted, taught me how to use his CB radio and he never had one drink. It was a good week. People can surprise you.

When I was 16, my stepfather took a rotary dial telephone in his right hand, held my mother down with his left hand and bashed her repeatedly over the head. The blood spurted out of her like water from a drinking fountain — straight up, then cascading down all over the floor. I held a knife to the back of his neck. He stopped hitting her. The police came. He was taken to jail. My mother left in an ambulance. When she returned home she had a shaved head with stitches crisscrossing like railroad tracks. My mother told me he was sorry and he promised he would never do it again. I told her I was leaving.

What we allow will continue. What continues will escalate.

He told me I could take whatever I could fit into one suitcase. Everything else, he reasoned, was his. He had paid for it. I skateboarded to my job working nights at Burger King to pay the rent. For the first time in my life, I did not live in my own house. I slept through the night. And I didn’t have a deadbolt.

I was known as The Girl Who Lived In The House Where the Ambulance Came or simply Ambulance Girl. Arleen didn’t care what they said about me. She was my best friend. She was a round, cozy Latina, happy as a Buddha. I loved her. She came to my track meets. So did other members of my family, concerned about me. They saw me fall into Arleen’s arms after a brutal race.

“Don’t you have any other friends?” I said yes. But Arleen’s my best friend.

“Arleen doesn’t belong here.”

They smiled. The same smile of kindness on their faces that I saw on the locksmith in New Orleans. What does that mean, I asked? Of course Arleen belongs here. She literally goes to the same school that I do. Why is she different? Don’t you have any other friends, they asked again? Our school was half-Mexican, half-white. We had no black kids, no Jewish kids and one Asian girl, Thanh, who had just transferred in. Thanh was my other friend.

My mother would let me know when my stepfather was gone and I would pick up my little sisters and take them to the park. My mother and I behaved like divorced parents who only spoke because of the kids. But when I saw her next, I blurted out what they said about Arleen. Her green eyes hardened.

It was my mother, after all, who rescued feral kittens and damaged people from alleys and gave them a home. Although she couldn’t defend herself against her attacker, she defended me. She said I could choose any friend I like and to fuck them. It was then that I realized I’d never heard my mother say a curse word — or a racist, hateful word.

I was eight years old. My grandmother and I were wearing matching overalls inside “The K-Mart.” My grandmother was shuffling through coupons when she suddenly reached out and grabbed me by the arm. I stopped short. She pointed out a little black boy my age who was shopping with his mom.

“This is what I’ve been trying to tell you about them.” She said in her Southern accent. “Look at his ears. He’s got tiny ears.” I looked at his ears. They looked like normal kid ears to me. “Tiny ears are the mark of the Devil.”

My grandmother was born in the backwoods of Kentucky, the youngest of 13 children born to a fire-and-brimstone Baptist minister. He taught them to love Jesus and he beat them across the back of the legs with a switch to keep them in line. They grew up in a cramped two bedroom house with no electricity. The Devil got a hold of her older brother. She fought him off when he tried to rape her in a shared bed. He wasn’t punished. They prayed for him.

She dropped out of school in 8th grade and got married. At 16, she gave birth to my father. Her husband went away to war. He returned home wounded and died. She moved from state to state, working in factories by day, waitressing by night. She was a single mother who paid her taxes, did the right thing, but there was never enough money and she never fell in love again. Over time, she wore her own scars and bruises from life, just as the locksmith.

She used the N word. A lot. The Little Boy’s mother heard her use it in K-Mart. So she hurried him away. But not before I saw the hurt in her eyes. Like my mother’s eyes when she became a bowling ball. I collected that hurt.

The people who raise you, they don’t just teach you to put on your clothes and look both ways when you cross the street. They also teach you words. They teach you how to speak about people who look differently than you do. They teach you how to respond to crisis. Do you remain silent and let it pass or do you speak up and call for help? They teach you what a lover relationship looks like. Does it look like a partner who shares the responsibility of cooking dinner? Or does it look like a partner who smacks you to the ground with his fists because dinner isn’t on the table?

My grandmother took care of me when my parents couldn’t. She loved me something fierce, so much so that I wrote a movie about her. When I was a teenager, I asked her to stop using the N word. She was defensive. We’ve always used that word. I said, it’s a racist, hurtful word. She was angry, but there was something else — anguish. She knew she shouldn’t be using the N word, but she needed it. So she held on tightly, not letting me take it from her.

In college, I fell in love with a boy named Kelvin. He was kind, prone to pratfall and we both felt like outsiders. I was a theatre major in a predominantly pre-med school. He was black. Kelvin wasn’t the Devil. He was studying to be a doctor. Unlike my father’s mother, my mother’s parents came from a wealthy, conservative family. They spent thousands of dollars trying to save my mother. They hired lawyers, sent her to year-long rehabs and paid for therapy. Nothing lasted. They also helped me. They sent me $100 a month to help pay for my college expenses and they bought me a car.

When I introduced Kelvin to my grandparents after a play, their reaction was faster than it was at the track meet with Arleen. They got up out of their seats, turned their backs on us, and walked out of the theater. Days later, I received a letter telling me they were heartbroken. He may be a nice boy, but imagine what the neighbors would think if they saw a black boy walking up to your front door? I had disgraced myself and our family and I would no longer be receiving their monthly $100 check. I was in school from 9am to noon and waitressing at Bob’s Big Boy from 4pm to midnight. With their help, I was lucky to have $20 bucks left over each month as it is.

Kelvin said we should move in together. It would save us both money. I would like to say that I was courageous. That I, like my mother talking about Arleen, told my grandparents to fuck off. I would like to say that I told Kelvin I loved him and let him swing me around the University Avenue laundromat as we folded our clothes together. That would be the movie ending.

After all, I recognized what my grandparents were saying was wrong. And it was unfair. And it was racist. But I was not able to do anything beyond recognizing that.

I was 21. Early in the morning, when my mother was sober, a car accident took her life. My mother had abused alcohol, and she had been abused, for over a decade. But if you looked closer, looked gently, you could see she’d long been on the road to an early death. So I broke up with Kelvin coldly and abruptly, never really giving him a reason. I needed my family.

At 25, I dated a woman for the first time. Leura. I told my grandmother. She wasn’t thrilled but, she said, when push comes to shove, a white girl is better than a black boy. Leura was invited to my grandmother’s house. She was fed fried chicken, collard greens and corn bread. She and my grandmother bonded. I went to bed early and they stayed up late playing Pinochle. Leura wanted to move in with me. So I broke up with her.

When my grandmother was dying of lung cancer, her roommate in the hospital was a black woman her age, also dying of cancer. Death united them and they became deep and fast friends. They finished each other’s sentences and watched the same soaps. They shared a love and familiarity that could only come from 50 years of marriage — or from realizing the outside world will never understand what you’re going through and you only have each other.

I was visiting them both in the hospital when my grandmother said, simply: I was wrong to use the N word. And I was wrong to tell you all those horrible things about black people. It’s what my daddy taught me and it was wrong. She said it in front of her roommate, who listened but never said a word. It was a movie ending — and it was true.

At 34, I was invited to a dinner party at the candlelit Chateau Marmont. In our red velvet booth sat the famous and semi-famous in plunging necklines, tight pants, expensive jewelry and perfectly manicured nails. They were all white, all straight, all in couples except for one man, who I realized was invited for me, the other single person.

Like most kids from dysfunctional homes, I’ve never felt good enough. Especially in heightened situations like these, that overflow with money and prestige. The clues are all there. I eat too fast, from years of half-hour breaks during waitressing shifts. My nails aren’t manicured. I’m quirky, not coiffed. But it’s something more. It’s who I am, the way I move. I’m just not put together enough and it’s only a matter of time before they realize I’m a fraud. So as superficial as it was, to be accepted by fame and fancy was a thrill.

After a few drinks the homophobic comments began. I was surprised because these were successful folks in the film and television community. Surely, we’re not like that? We work with gay people every day. But this is how casual racism and casual bigotry works. It works with two faces. The public face, where all the right words are said. And the private face, where your mother is beaten and kids are told to keep their mouths shut or else.

I said with a smile, hey. I don’t think those comments about gay people are cool.

“Are you a dyke or something?”

He asked. Not unkindly. I was floored. His question implied that to stand up against a racist or bigoted thought, you must secretly be one of them. Because no straight person would call out another straight person over a gay comment. No white person would call out another white person over a racist comment.

I was angry because I had slept with a black boy and a white girl and that lessened, in their eyes, my defense. I was angry because they could see the answer on my face and I could feel their relief. I was the one to blame. I had hidden myself in plain sight. But Kelvin cannot hide in plain sight. Whenever he walks down the street — he’s a black man. Arleen can’t hide in plain sight — she’s a brown woman. And even if a gay person can put on the straight mask and hide in plain sight walking down the street, they should not have to drop the hand of the person they love to feel safe.

I looked at the man, “You just said a pretty hateful comment about how ‘faggots’ are taking over Hollywood and that a faggot actor got a job that you think you deserved, rather than thinking just maybe that actor had more talent than you did and deserved the role.”

Now they were angry. No one likes to be called a racist or a bigot. Despite what they say or do.

I continued, “But to answer your question. Yes, I’ve slept with women. But if you think that means calling you out doesn’t matter as long as straight white people give you a pass, then we’re going to be waiting a long time for this world to change, because what you said is not okay.”

When I was done, my voice was shaking. My heart was pounding in my throat. I looked around the table, just as I had looked at all the adult faces at my 13th birthday party. Anyone going to help me out? I looked especially close at the women. Anyone have my back here? They, like my mother, looked away.

I picked up my purse and walked out of the restaurant. I have no idea if what I said made a difference to anyone at that dinner party, then or years later, but it did to me. Because I didn’t let it slide. I’ve learned what letting it slide does to a person.

The racist waving his flag isn’t a surprise. I see him. You see him. We all know what that’s about. But racism and bigotry don’t always march down the street. Sometimes the racist or the bigot sits down at your dinner table and asks you to pass the bread. Those are the ones who surprise you. Racism grows and festers in intimate spaces and behind closed doors. In the words spoken by the people you know and love and who look just like you.

Should I have kicked out the locksmith? Should I have stormed out of the restaurant? Would you have?

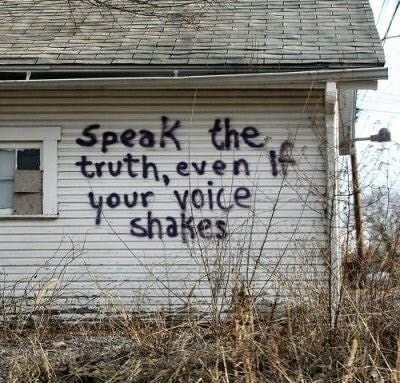

Letting a comment slide can feel like a deadbolt sliding over your soul. And speaking up doesn’t always feel like a victory, especially in the moment.

What we allow will continue. What continues will escalate.

May you always have the courage to speak out. And when you do, may it unlock the soul and warm the chilliest of rooms.