When Race Meets Adoption

By Andrew Drinkwater

Baby me meeting my (adoptive) parents in Bogotá, Colombia for the first time.

It felt the familiar buzz of my phone in the pocket of my jeans as I walked with a friend back to my dormitory. A Snapchat? A GroupMe message? Maybe even a Facebook message? I fumbled for the slab of connectivity and glanced at the screen. Nothing. An email, I thought to myself, as I opened the phone with my thumbprint. I broke paths with my friend as he headed to the dining hall, just in time to open the email app. A new email had reached my inbox. But this was no typical email. I stared at my phone screen in wonder and anticipation. It seemed funny, in that moment, that an email could contain secrets about me that I long yearned to know but never expected to be revealed.

I was nervous. With the answers at my fingertips, the weight of what I was about to learn gave me pause. The story of me was one I was quite familiar with, if not completely settled into. Would the story change when played in color?

I was born to my biological mom in Bogota, Colombia. We were separated 3 months later.

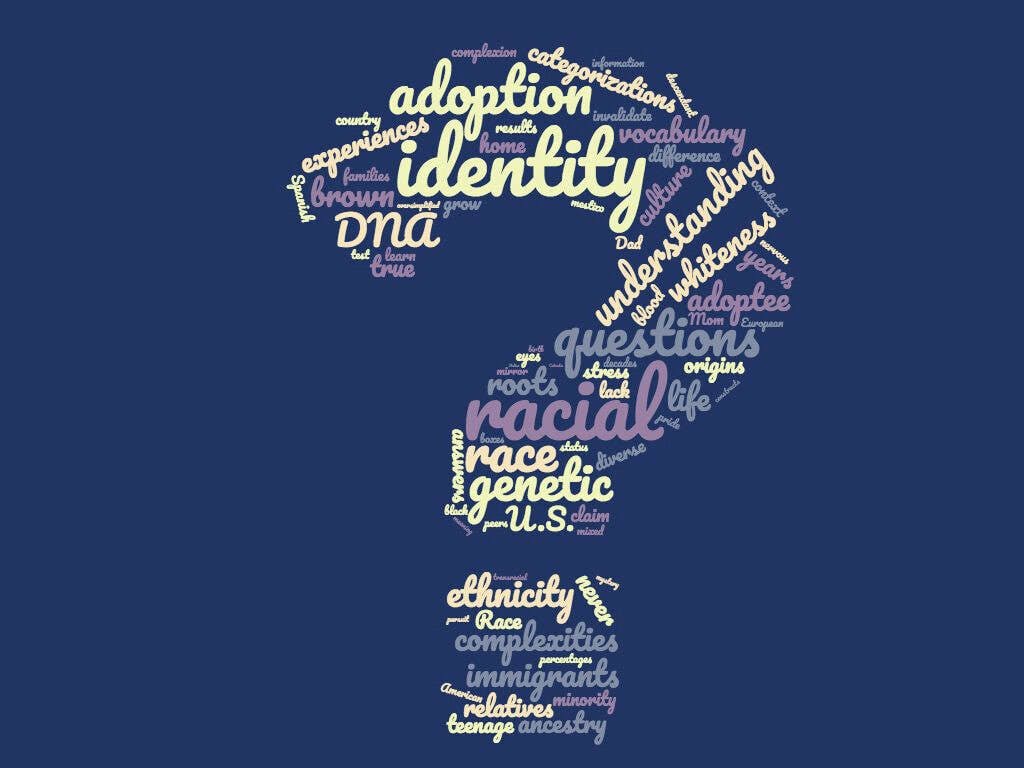

This past year, I took a genealogical DNA test in an effort to discover more about my ethnic and racial background. As an individual born in Colombia and adopted by American parents at three months old with no information about my racial identity, this test was an incredibly important moment in my life. Race so often forms a powerful aspect of our stories and being unsure of my racial identity for the first two decades of my life has shaped mine.

Racial identity is complicated for many people for many reasons. For many adoptees, racial and adoptive identities exist in a complicated relationship. For example, many adoptees have no relatives that share their racial-ethnic roots, which is true in my case.

Racial identity in the context of inter-country adoption can be even more complicated. International adoption involves an individual from one country being adopted by a family in another country. For American families that adopt internationally, most parents tend to be white, and the adoptees tend to be of racial backgrounds that designate them as minorities in the United States. Many, although not all, are transracial adoptions, meaning that the race and ethnicity of the adoptive parents differ from those of the adopted child. I am a proud international transracial adoptee.

My awareness of my racial difference from others began very early in my life. Often adoptees develop a more complex sense of identity at a much earlier age than non-adoptees due to their non-normative upbringing. My parents were always quite honest and upfront with me regarding my roots as well as theirs. They told me all they knew, that I was Colombian (a fact I held and still hold with pride, although for context, trying to decipher race from this mere description is like saying that someone is born in the United States and then trying to guess what their racial background might be), and I knew that my birth-mother had lacked significant financial means (another clue?). “Colombian,” from the age that I could first derive meaning from such designation until later in my teenage years, only meant that I was Hispanic and Latino. Beyond these categorizations, I had no real information to go off of.

I came to conceptualize Hispanic/Latino as a racial category. I still consider it to be a dominant part of who I am, but this internalization of my race as Hispanic without understanding the true complexities of the term came to be a source of stress later on.

I was raised in New England, far from my country of origin.

I knew, almost always it seemed, that I was not white. Or at least not white in the same way as my parents. Dad, a descendant of Italian immigrants, and Mom, a descendant of Irish immigrants, behaved, appeared, and talked in ways that I had been conditioned to associate with whiteness. And for a long time in my life, I thought that whiteness simply equated to having European origins, due to a lack of understanding of the historical evolution of racial constructions that have guided our perceptions of race, an understanding that I would grow more familiar with as I grew older.

I often contrasted the whiteness of my parents with one of the only things I knew for sure about my identity that they didn’t have: my Hispanic and Latino roots. Although I now understand these categorizations to be more ethnic than racial descriptions, as a young adoptee searching for a meaningful self-identification in a world that forces you into boxes, I clung to this identity. My white adoptive family had never had to think about racial-ethnic identity before and lacked the the vocabulary to set me straight. I came to conceptualize Hispanic/Latino as a racial category. I still consider it to be a dominant part of who I am, but this internalization of my race as Hispanic without understanding the true complexities of the term came to be a source of stress later on.

As I continued to grow into my teenage years, my identity again became a source of deep introspection. I would look in the mirror and see a face with a complexion just tan enough to perhaps elicit outside skepticism about my potential whiteness but without the darkness to firmly establish my identity as one of minority status. Although years later I would recognize that this lack of clarity regarding my racial status gave me considerable privilege, being perceived as alternately white or ethnically ambiguous was remarkably disorienting. I looked into my eyes in the mirror, searching for answers that I knew I might never receive. In some ways, I knew the answers laid in those eyes, the same eyes passed on by my birth-parents. My eyes, my hair, my nose, my skin. All clues. All containing their own secrets, their own stories. But to the teenager looking into the mirror? Only mystery.

I had also begun to question the validity of my identities or at least my claim to them. Could I claim to be of Latino descent when I didn’t speak Spanish and never ate Colombian dishes at home? Did I have a right to claim such an identity when my experience differed so much from others who did?

I had internalized my race as Hispanic/Latino for years; I had even found comfort in it. That comfort quickly unraveled in my late teenage years: if being Hispanic or Latino is an ethnicity, what was my actual race?

For those of us that fall between the boxes, this seemingly easy question becomes daunting.

These questions only grew louder as I entered college. First came questions on the Common Application about racial background, when the oversimplified boxes placed on the screen in front of me seemed to invalidate my life experience. Hispanic/Latino was not included as a racial category, forcing me to identify with something else. I was certainly not Asian or black, but I had also never considered myself white, despite my upbringing and my family. Do I check it off? Would it seem ignorant not to? I left it blank in frustration and anguish. (After all, this was supposed to be easy part of the Common App, right?)

To add to my confusion, Hispanic/Latino, as I had begun to recognize and consequently fret over, was framed as an ethnicity. I checked off the box and moved on and drowned my thoughts in the next tedious task within the application form. This identity question, however, lingered beyond college applications. I had internalized my race as Hispanic/Latino for years; I had even found comfort in it. That comfort quickly unraveled in my late teenage years: if being Hispanic or Latino is an ethnicity, what was my actual race?

This question outpaced the deepening understanding of race I would gain in college, giving rise to massive insecurities. As I met new friends and peers at school, ones that came from more diverse families and backgrounds and places than I had ever even imagined growing up, my own identity questions and racial uncertainties consumed my thinking. Some of my peers even unintentionally invalidated my experience, saying things like, “But, you’re basically just white.” These and similar situations led me to struggle to gain a firm comfort in my identity early in college.

I longed to understand how race played a role in the life of my birth-mother. And I hoped knowing my racial identity would help me better understand my place in the world.

In the few years since that time, I have become comfortable and confident in who I am, racially and otherwise. I understand better the complexity of race, adoption, and identity, nuances I have learned by asking questions and pursuing relevant opportunities and experiences at college and beyond. In growing to better understand my adoptive identity, I have become more comfortable with the complexities of how my racial and adoptive identities interact, and I have even gained a comfort with the realization that I may never understand the complexities one hundred percent. It has been liberating to know that there will always be more I can learn about myself and who I am.

I have grown closer to Hispanic and Latino peers and culture, allowing me to have experiences that I was never able to while growing up. This has given me an immense confidence in my Hispanic/Latino identity. I recognize now that I have a legitimate claim to that identity, a claim that no one can take away from me.

Still, despite this newfound embrace of who I am, the question remained around my true racial identity. I longed to understand how race played a role in the life of my birth-mother. And I hoped knowing my racial identity would help me better understand my place in the world. Out of this curiosity came my pursuit of the DNA test.

I had prepared for so many different scenarios that the results did not come as a complete surprise. I discovered that I was of mixed racial origins, someone who, in the country of my birth, would considered mestizo.

The results were laid out in terms of ethnic origins. Although race and ethnicity are social constructs, and thus not natural or able to be detected biologically, our DNA can reveal genetic similarity between people who are closely related by blood. This process allows the service to essentially track your blood across time and look back thousands of years to see where the ancestors of my bloodline and individuals with similar DNA came from. They can also break down the regions of ethnic origins into specific areas around the globe, and then provide fairly accurate percentages of DNA that are associated with ancestors from a specific area.

Reading through my specific results was a transcendent moment. I was reading, mapped out in numbers and places and names and descriptions, a part of my story. A part of who I was, of the blood that pumped through my heart and ran through my veins. I thought of my parents. I thought of my birth-mother. I thought of me. And I smiled.

I had prepared for so many different scenarios that the results did not come as a complete surprise. I discovered that I was of mixed racial origins, someone who, in the country of my birth, would considered mestizo. I contained DNA from European ancestors, helping to ease my decades long question of whiteness, but also contained almost as significant percentages of DNA from indigenous American ancestors. I had never explicitly considered the possibility of being part indigenous, which has certainly begun to reshape my conception of the person I am. Combined with the revelation of whiteness as well, I have come to conceive myself in new and glorious ways. Since many Latinos fall into the category of mestizo, or mixed racial origins of European and indigenous ancestry, I have also gained a newfound pride in my status as a Colombian- and Latino-American.

And while I have received an answer to one big question, it does not come without new questions. How did these identities play into my birth-mother’s life? How do these newly discovered identities interact with my adoptive identity? How do they inform me of the principles I hold, or of my place in the United States? In the world? Wherever these questions lead me, however, I hope that I continue to have many more in the future. In my experience, such questions lead us to our truths.

And sometimes our truths really do set us free.

Andrew Drinkwater