When Kids Get it All Wrong. My Early Days As A Racist

By J.P. McCabe

The morning after James Earl Ray murdered Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., I celebrated his killing with another fourth-grade classmate at our elementary school in a suburb of Eastern Massachusetts. It was the first thing we did that morning before we went to homeroom.

Word of Dr. King’s murder had struck during the evening news the night before. Walter Cronkite announced it to the country as it was happening. My uncle and grandmother had come to visit from where they lived together nearby. We were saying our good-byes in the driveway when my older brother came running from the house. “Someone just shot Martin Luther King.”

“Oh great,” my father said. “This is gonna be trouble….” He and my uncle exchanged knowing looks.

Why my friend (let’s call him Timmy) and I were in the hallway rather than homeroom when school started the next morning, I can’t recall. But there we were, two 10-year-old white kids, in an all-white school, in an all-white town, arm in arm, skipping along as we chanted, “Martin Lootin’ Rootin’ Tootin’s Dead! Right! Martin Lootin’ Rootn’ Tootin’s Dead! Yeah!”

As I think back on this 50 years later, we seemed quite pleased with ourselves. Where we got this little rhyme from, I have no idea. Did we make it up? Did we hear it at the dinner table? Was it something white adults around us were saying in response to news coverage of the civil rights movement? I don’t remember. But I remember very well, my fourth-grade homeroom teacher (Miss Jones, we’ll call her), a young woman from Alabama with strawberry blond hair, freckles, and a luxurious Southern accent. She stopped us in our tracks.

“What do you boys think you are doing?” she asked. Not angrily, if I recall, but more a look of stunned concern. I remember looking at her, then at Timmy, then at the ground. Suddenly it seemed, in fact, that we had no idea what we were doing. Or maybe we thought we did, but now it didn’t seem like such a good idea as we faced Miss Jones.

Miss Jones didn’t send us to the principal’s office or punish us in any other way. But I remember her firm grip on our shoulders as she went to one knee, searching our faces. Then she told us to go to class.

Coretta Scott King at her husband's funeral.

What were we doing? Two 10-year-old kids in a segregated Northern suburb, one of Irish, the other Italian descent. I honestly don’t know. This was 50 years ago. What was I thinking? I can’t speak for Timmy. I found him on Facebook recently and asked him about incident. He remembers it the same way I do, but I will speak only for myself.

The fact that I came from a white-ethnic household was a strong influence on my childhood, even if the streets of South Boston were 12 miles and a generation from where I grew up. We still had a family construction company there. My father spent most of his waking life in South Boston running the company.

His father, who was born in the South End, which was poorer than South Boston, had created a successful business from very little. A blacksmith by trade, he acquired horses, then carts, then trash hauling contracts. He bought a barn and a yard in South Boston, then he got into construction. That was in the 1920s, ’30 and ’40s. My grandfather became quite a high roller, and moved his family to a wealthy suburb west of Boston.

We all grew up with a good deal of privilege. In the suburbs, the Irish part of our identity meant less and less. But my father did not go to college. He took over the family business at 509 E. 1st Street after my grandfather got sick. South Boston was his life. He didn’t want us to forget that.

Six years after MLK's murder, opposition to desegregation of Boston public schools by busing was fierce among whites in parts of the city, most notoriously in South Boston. Photo: http://www.lib.neu.edu/archives/freedom_house/full_text/racial_cover.htm

Could South Boston roots explain my behavior that morning, or at least some part of it? James Earl Ray murdered Dr. Martin Luther King on April 4, 1968, a full six years before the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts ordered the desegregation of Boston public schools via a busing plan. The infamous busing riots that followed left a stain on South Boston and the city as a whole for years to come. We heard all about those riots at my dinner table day after day as they played out. My dad would buy a sandwich for lunch and drive up to South Boston High School to watch the action. He gave us the play-by-play every night — cops beating kids, kids beating cops, kids and parents stoning buses.

But that was 1974. Were there earlier events stirring in South Boston that could have influenced my young thinking on race relations? Indeed there were.

The busing plan that exploded in 1974 had its roots in the Massachusetts State Legislature’s Racial Imbalance Act of 1965. It declared that any school that had more than 50% non-white students would risk losing state funding if not desegregated. Almost all these schools were in Black neighborhoods in Boston: Roxbury, Dorchester, Mattapan, and the South End. White schools to be integrated were in white working-class neighborhoods in Boston: Roslindale, Hyde Park, South Boston, Charlestown and the North End.

Long before the court imposed the busing plan and all hell broke loose, a little known Boston School Committee member and then Committee chair representing South Boston, Louise Day Hicks, made local and then national headlines by adamantly denying that segregation was a problem in Boston City Schools.

Hicks appealed directly and openly to fears about race and race mixing. She presented herself as the defender of poor and working whites and the Irish of South Boston in particular. As a School Committee member she openly obstructed planning and implementation of the 1965 desegregation act right from the start. Hicks’ appeal was huge. In 1967, she ran for mayor and lost to fellow Democrat Kevin White by just 12,000 votes. Hicks’ slogan was, “You Know Where I Stand.”

This was all over the news back then. Liberal integrationists compared Hicks to Bull Connor and George Wallace. Hicks was indignant, claiming she abhorred Jim Crow and Southern white supremacy. She then went on to publicly admit, “while a large part of my vote probably does come from bigoted people…I know I’m not bigoted.”

In 1965, Boston School Committee member representing South Boston, Louise Day Hicks, ran for mayor as the anti-integration candidate and nearly won.

Playing both sides of the racial street was common among the Boston Irish. My mother certainly harbored many negative attitudes about Black people, but she never used racial epithets and she never failed to castigate my father when he did.

“Joe!” she would scold. “We are not pigs-in-the-parlor Irish….” She identified overt racism with being ignorant and low class. My father, for his part, did not use the N-word that I ever heard, but certainly used many other epithets, not only for Blacks, but for Jews, Asians, and anyone else he saw as different. He would snicker naughtily as my mother scolded. We kids would snicker, too, the same way we would if Dad had burped or farted. This was the standard dinner table routine.

Oddly, my father drew a line of sorts on racism as well. There was a man in town (Mr. DuLain, we’ll call him) who was well-known to be an avowed racist. My father never tired of deriding him as an idiot. “Boob” Dulain, he called him. “Boob has always been the dumbest guy in town. He got that name back in grammar school,” my dad would chuckle. So it seemed my father recognized that overt racism carried with it a social stigma that he did not want to bear publicly, even if he used racist language behind closed doors.

It was my grandparents’ generation who were frankly unrepentant about their prejudices. My mother’s mother was 100% Irish from the working-class city of Watertown outside of Boston. She had an unkind name for anyone and everyone who wasn’t Irish. Dagos, Sheenies, Spics, Chinks, Jigs — you name it, she didn’t like ’em. She would cluck her tongue disapprovingly when any of these perceived “others” appeared on her television set. But she was particularly outraged by the growing presence of Blacks in the news media, sports, and entertainment. “What’s he doin’ on there!” she would snap every time a recently hired Black reporter appeared on one of our local TV news stations.

Most years when I was a boy, we went to the St. Patrick’s Day parade on Broadway in South Boston. It was a big deal for a kid of 7 or 8. The City sights, the hard-looking people, the shamrocks blazing everywhere, the parade. Louis Day Hicks was always a guest of honor back then, waving to the crowd from an open-top Cadillac, the trademark bouffant heaped high on her head. I remember the South Boston version of the KKK applauding her as they stood in front of the Bright Star Bar. They did not wear hoods, but dressed all in white, with white skally caps (a working man’s snap brim hat), and they wore the words in bold black letters across their T-shirt fronts, “NI#@ERS SUCK!”

So yes, I think we can say there were events related to my Irish-American upbringing that would have influenced my young attitudes about race relations, even if I bore witness to many of them from the safe suburban sidelines.

Remember as well that in the 1960s there was little if any mention of the civil rights struggle in the elementary school curriculum. Events were still playing out. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 had only just been passed. Court struggles over their implementation would go on for years. Dr. King received the Nobel Prize in 1964, and we may have been told about that in school, though I can’t recall. But the heroic civil rights narrative that children learn about today had not yet been constructed.

As kids, we were largely left to our own devices to interpret what race relations were all about. Having no direct experience with Black or brown people in our segregated world, the totality of our knowledge came from news reports which often portrayed the civil rights struggle as disruptive, ominous, and potentially violent.

Archival video of Cronkite’s reportage on the night of Dr. King’s murder shows him giving a dignified account of King’s accomplishments, but Cronkite also makes mention of riots and the threat of riots four separate times in four minutes. He makes mention of H. Rap Brown and Stokely Carmichael. He associates Blacks, civil rights, and the potential for violence repeatedly during his report. Is this the kind of spin I would have heard back then and in the years leading up to Dr. King’s assassination? Almost certainly.

On left: Snowshoe with Charlie Chan. On right: Birmingham Brown with Charlie Chan.

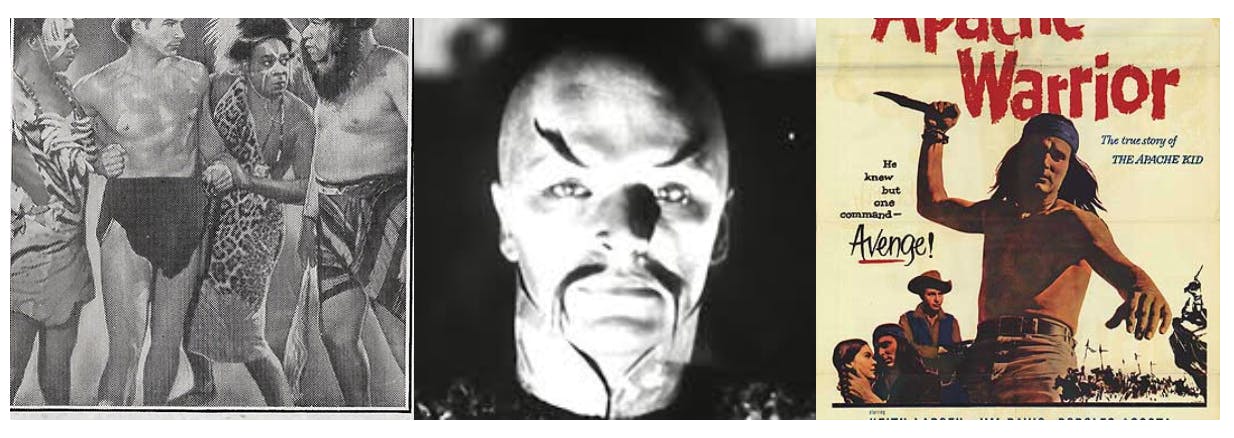

Another set of strong messages we got over and over about people of color in those days came from the black and white B movies and shorts from the 1930s and ’40s. We loved this stuff. The Three Stooges, East Side Comedies, Tarzan, Little Rascals, Charlie Chan, Mr. Moto and old Westerns.

When these films showed Black or brown characters at all, they were generally portrayed as foolish, lazy and superstitious. Lincoln Perry, Hollywood’s first black millionaire, went by the stage name Stepin Fetchit — the world’s laziest man. Stepin Fetchit played Charlie Chan’s black manservant “Snowshoe,” in the 1930s. Mantan Moreland took over the role as “Birmingham Brown” in the 1940s. As a kid of 8 or 9, I had a knack for doing impressions: Bing Crosby, Dean Martin, Jimmy Durante, and I did excellent versions of Stepin Fetchit and Birmingham Brown. The kids in the neighborhood really loved it.

On the flip side of this, other film genres portrayed people of color as threatening and violent, particularly in Tarzan movies and Westerns, but also in matinee mysteries like Fu Manchu. My friends and I knew all this stuff by heart. We would recite scene after scene, line after line. The more degrading the line, the funnier we thought it was.

By the time of Dr. King’s murder, a kid like me would have had a very definite, if utterly ignorant, worldview on matters of race. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that I concluded that the killing of Dr. King was a good thing, or at least not serious. I had never seen a Black person serve in any capacity other than comic relief or sinister threat. A Black man’s murder was either a joke or something to celebrate. Right?

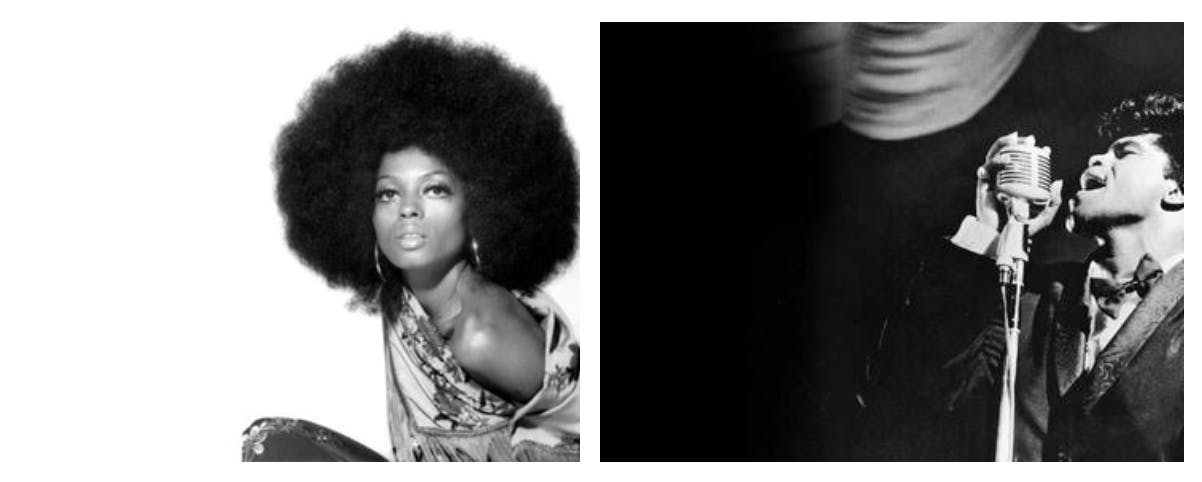

Through all this dimness, there was a ray of light. During these same years I grew intensely interested in pop music, like most kids. Top 40 radio has never come close again to the heights it reached in the mid-1960s. There was plenty of kid stuff (the Monkees, etc.), but I remember being blown away by James Brown’s “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” when it hit in 1965. I would make my dad blast it every time it came on the car radio. The Temptations, the Miracles, the Impressions, the Supremes, Gladys Night, Stevie Wonder. I was totally captivated by them all, particularly Diana Ross when I first saw her on The Ed Sullivan Show — she was the most glamorous girl I’d ever seen.

This profound and growing love of Black American music coincided with my beginning to play guitar and, over time, starting to identify as a musician. Struggling to make music and developing a pantheon of musical heroes became truly trans-formative as I approached my teen years. In the beginning, though, my new pop heroes coexisted comfortably in my mind with all the negative stereotypes I’d grown up around, maybe the suburban white inverse of what W.E.B. Dubois termed Black “double consciousness.”

I think it was the Jackson Five’s “I Want You Back” in 1969 that really liberated me. Michael and I were both 11 at the time, and that made discovering him very personal to me. Michael was on Ed Sullivan, singing and moving like nothing I had ever seen before, while I was sitting in my room struggling to play an F chord. I remember feeling profoundly inadequate, but very much in love.

As a teenager, I kept going deeper and deeper to the well of Black American music. In soul, blues, and jazz I found an inexhaustible source of inspiration. Most of my heroes now were Black, and not just in music, but in the world of sports and entertainment.

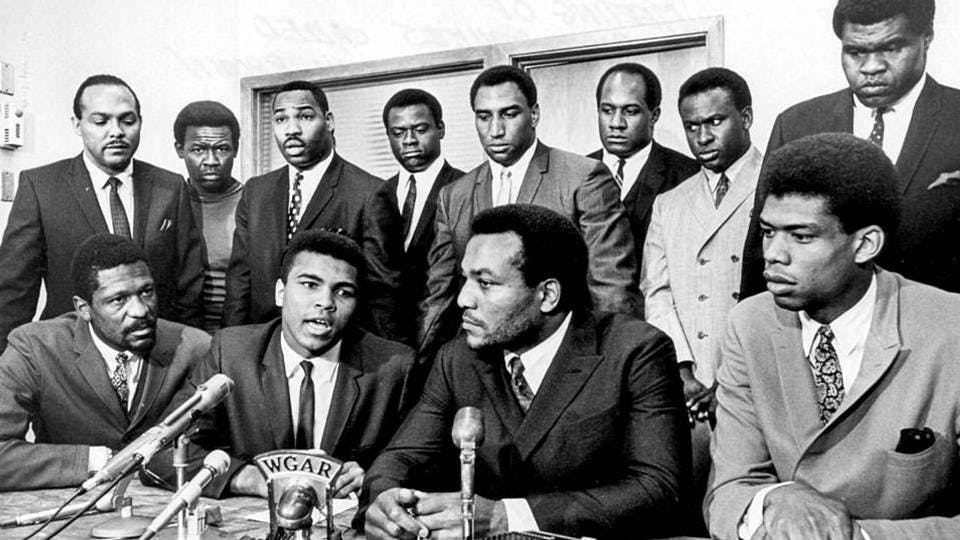

As I write these words, they sound almost trivial. Music, sports, and entertainment? But if you are old enough to remember, Black stars in all fields were presenting themselves in new and powerful ways — not just James Brown, Curtis Mayfield and John Coltrane, but Jim Brown, Bill Russell, Muhamad Ali and Kareem Abdul Jabbar too— and teenagers like me took notice. I was still living in a completely segregated environment, but my thinking about Black people was now quite different from that of the 10-year-old who celebrated the killing of Dr. King, figuratively dancing on his grave, just a few years back.

On June 4, 1967, big-time black athletes and civic leaders gathered for the "Ali Summit" in Cleveland to show support for Muhammad Ali's refusal to fight in Vietnam.

I am not looking to unburden myself of guilt for some stupid thing I did 50 years ago. Out of the mouth of babes often comes the truth, as ugly as that truth may be. These memories resurface at a time when we find America still deeply divided along racial and ethnic lines, and these divisions are being exploited and expressed in ways every bit as ugly as the things I saw and did as a child. And saddest of all, it now looks like my child will have to experience so many of the same things I did, all these years later.

In the late-1950s and early 60s so much of the culture that enveloped my earliest years was profoundly backward looking, still steeped in the overt racism of the 1930s and 40s. By the late 1960s and early 70s, however, I was getting new, forward-looking cultural messages from all sides. I was born on the cusp of a cultural revolution, and my young consciousness, thank goodness, went with that flow.

My personal life today is multiracial and multicultural in ways I couldn’t have imagined at 10. My adult life has been blessed with close friendships, romances, and a marriage of 16 years — with people of color — and I’m father to a beautiful brown child of 8. These experiences have literally been transcendent. In the 40 years I have lived away from the Boston area, I outgrew my segregated roots. Thomas Wolfe once famously said, “you can’t go home again.” I wouldn’t want to.

Why share such a singularly stupid and ugly act so publicly? It occurs to me that just as social media has recently been used so powerfully by the “Me Too” movement, there may be an analogous value to sharing personal experiences with racism and other forms of hatred, whether these memories are of things we saw happen or of things we actually did ourselves — and by “we” here, I mean white people.

At a time when too many whites seem motivated by an urge to deny the persistence of racial injustice, whether that be by denouncing Black Lives Matter as a hate group, criticizing NFL players as unpatriotic for taking a knee, or countless other acts of self-deception, white people of good faith might make a difference by sharing what they know.

If some whites are tempted to use their majority status to silence people of color on issues of social injustice, other whites can use our voices on social media and other public fora to tell the truth about the things we have seen — and what we have done. Would it make a difference? It could. We damn sure don’t need to make America like that again.

If shame and fear of reprisal kept women silent for years about rape and harassment, the same is certainly true about whites and racism. If you saw or did something, speak out. Maybe the truth can set us free….