What the COVID-19 Crisis Tells Us about Structural Racism

Even as COVID-19 leaves its mark across the length and breadth of the United States, we know that some communities are being hit harder than others. The overrepresentation of Black and Brown people among COVID victims in New York City has received lots of attention because of the huge numbers involved, but the pattern repeats itself almost everywhere we have the data to document it. Join us for a conversation with Drs. Nicolás E. Barceló and Chandra Ford about why Black, Indigenous and Latinx communities are suffering disproportionately, why this pattern of racialized vulnerability is so painfully familiar, and what we might do to disrupt it.

This conversation happened on 4/16/20. The video is available here. The transcript and resources follow. Find out about upcoming webinars here.

Dr. Nicolás E. Barceló

EmbraceRace: Welcome to What the COVID-19 Crisis Tells Us about Structural Racism. We're Andrew and Melissa from EmbraceRace. Let me start by introducing our guests.

Nicolás Barceló is a medical doctor. He is a resident in general psychiatry. He's a former chief resident of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in the UCLA Department of Psychiatry Training Program. And next year will enter a post-doctoral fellowship in health services research at UCLA.

Nicolás Barceló: Good evening. Thank you for that generous introduction.

EmbraceRace: It happens to be your life, Nicolás!

Dr. Chandra Ford

EmbraceRace: And then Chandra Ford is an Associate Professor of Community Health Sciences and Founding Director of the Center for the Study of Racism, Social Justice and Health at the University of California of Los Angeles. Chandra and I met; I think it was four years ago now, right? 2016 on a yearlong panel on the community-based health programs.

Chandra Ford: Yes.

EmbraceRace: She became one of my favorite people that I hardly ever get to see. So I'm glad to make up for some of that now. And let me start by asking- this work and these conversations that we have, certainly this one, often attracts people, and the work often attracts people, who are personally invested in it. So, I gave just a taste, there's so much more to say about both of you. You're very, very impressive, lots of professional investment in racial equity work across the various populations in the arena of health in particular.

But can you tell us a little bit about what drew you to this work?

Chandra Ford: It's kind of funny because I've spent my entire academic career talking and thinking about racism as a public health issue. And I remember as a doctoral student that a number of my friends really were kind of like, “Okay well that's great, but, you know, the real public health stuff will come later maybe,” or something like that. And so fast forward all these many years and I think we're starting to see how this stuff really does matter for health and for wellbeing.

I hadn't really thought about why I got into this until recently a student asked me. And I had to admit that I don't think I would have done this kind of work were it not for my own personal frustrations early on as a young adult, with the lack of attention to issues of inequality when I was an undergraduate student studying clinical nutrition.

And so that really led me to sort of pursue this as an intellectual question. And that really has been the motivation. It's been a way for me to move it out of the personal, where the personnel is painful, and try to move it into the direction of trying to do something about it.

EmbraceRace: Chandra, I know again, because we've worked together and spoken since then, that you're bringing a lot of brain power to your work and also a lot of heart to your work. I mean your passion is pretty clear in what you do. Nicolás, you're a medical doctor and I have a bunch of friends who've been through med school and are doctors and even spoken to some recently trained folks.

And I am astonished, some of them continue to be astonished, by how little attention medicine to the racial equity side of public health. But there you are trying to get it done. Can you say a little bit about where you're coming from?

Nicolás Barceló: Absolutely. Just to kind of to begin, I couldn't agree more with what you're saying in terms of the reluctance of academic medicine and medical training for sure in terms of embracing the very concepts that Dr. Ford has been so important in kind of advancing, which is racism as a determinant. And a willingness to have kind of the brave conversations that I think we're having this evening around racism.

I can't tell you the number of times in which I've read the literature on health disparities and I opened an article and I do a Control Find racism and it's not there. And we're purportedly discussing disparities around race. And the word racism is not featured in an article. And that's something that I think has been something that I can't get my mind around.

I mean, I know many of the barriers that exist, including racism, that would prevent us from naming racism when it comes to disparities, but it's something that in my research is something that I've tried to prioritize. Like Dr. Ford, my interest in this work comes from personal experience coming from a family representative of many races, growing up in a very racially segregated agricultural community on the central coast of California. At an early age seeing disparities in health education, socioeconomic status that as a child were just overwhelming and terrifying and created a lot of anger in me frankly. And I think since then, it's been something that even when I become very interested in, for example neuroanatomy, I find myself returning to questions of equity and race. And so that's I think the short version.

EmbraceRace: This might be another conversation maybe we can weave some of it in here, but I know you mentioned anger. You're professors, you're an academic institution, a very significant one, elite one. I know it's amazing how often we are told that anger and even passion have no place. And yet I often feel like, if we can't get worked up about this stuff, what are we going to get worked up about if not this?

I mean, literally people are dying. So we'll obviously get into that. We typically as regular viewers know, we don't often go to slides, but this is actually a place where it seemed important to spend just a little bit of time showing some of the data. And talking a little bit about its limitations.

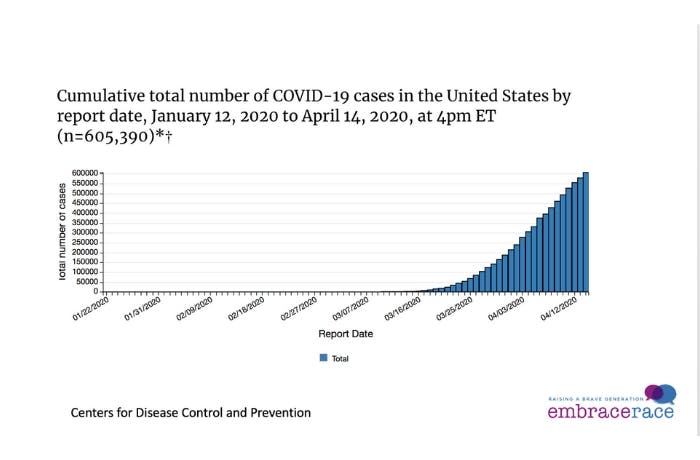

EmbraceRace: So, what you're looking at here are the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases. So total cases in the country as of the 14th, a couple of days ago. As of a couple of days ago we were at 605,000. Now a couple of days later, I think I saw 667,000 cases. This is a percent of deaths for which race ethnicity data is reported through a few days ago. Now I think the big takeaway here, there are at least a couple of them.

EmbraceRace: One only a handful of places, a handful of states, maybe a dozen states have actually reported racial data on who has died from COVID. So clearly it includes some of the big ones. That means there are a lot of people in a lot of places who dying and we just don't know racially speaking who they are. At the yellow bar there, near the bottom, that's all US deaths as of a few days ago. And what that shows us is that only in 35% of the cases, a third of the cases, do we know the racial identity of the person who died.

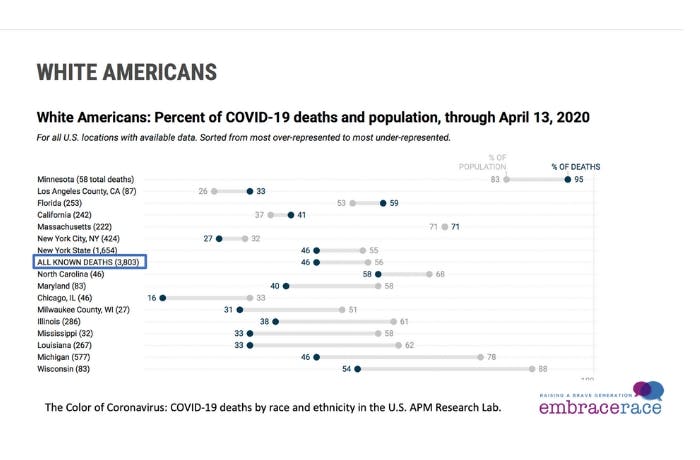

EmbraceRace: So again, lots of missing data. Then a breakdown by race- white Americans. So I put a bar again around all the white Americans, or identify as white Americans, who had died as of a few days ago. And what this tells you is that white Americans represented 56% of the population, the overall population in those places. So certainly, white Americans are a larger share of the overall population, but they were only 56% of the population in those places for which we have racial data, but they were only 46% of the people who died.

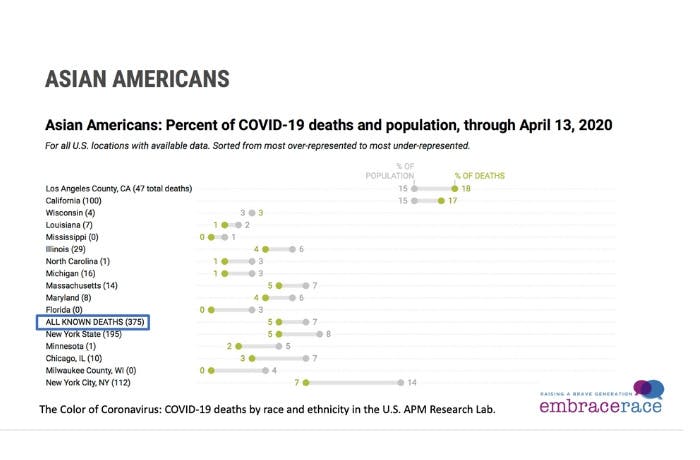

EmbraceRace: So, they are dying at lower numbers then their population would suggest. The same is true, according again to this very incomplete data, of Asian Americans. So overall Asian-Americans were 7% of the populations in those places for which we have racial data. And 5% of the people who were said to have died from COVID.

EmbraceRace: Black Americans, now this is pretty dramatic. It's actually even more dramatic than I realized when I started looking at this. 2,703 deaths of black Americans attributed to COVID as a few days ago. But look at these comparisons. They were 13% of the population in those places and 32% of the deaths. So you're looking at what? Two and a half times overrepresented among death.

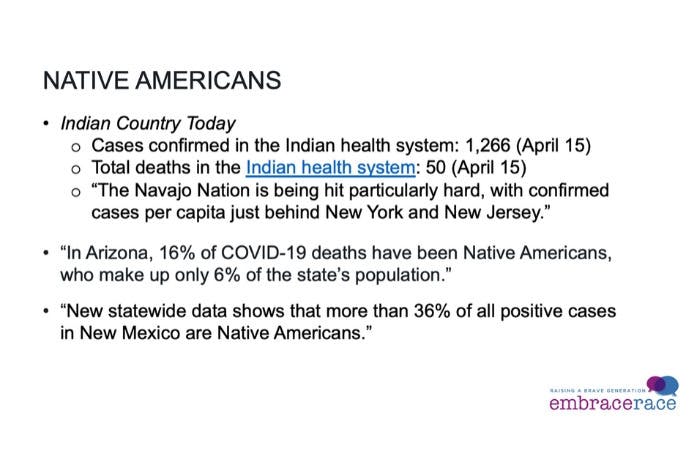

EmbraceRace: Native Americans, very hard to find good data. Nicolás especially, because I know that you do some work with native populations. Chandra, of course. In lieu of finding anything like good data, I just pulled a few snippets from news stories. So Indian Country Today is a news outlet which is trying to track the number of cases and deaths reported through the Indian Health System. 1,200 cases as of a couple of days, as of yesterday. Total deaths 50. And here's a quote: “The Navajo Nation is being hit particularly hard with confirmed cases per capita just behind New York and New Jersey,” which are one and two overall in per capita deaths. In Arizona 16% of COVID-19 deaths have been Native Americans who are only 6% of the population. So, they're overrepresented by a factor of three and Arizona of course has a large native American population.

The similar story about another large native population state, New Mexico, where they are 36% of all positive cases compared, by the way, to only about 11% of the population. So, they [native populations] are more than three times overrepresented among those dying from COVID in New Mexico compared to their population.

EmbraceRace: Latinx folks, this was also a real surprise to me, that according to the data that we have, they have been 21% of the population in these places, but only 14% of the deaths. So, the big exception is the one that's gotten outsize attention because New York City and New York state of course are the epicenter of this outbreak so far. In New York City, Latinx folks are overrepresented. They're 29% of the population in New York city, 34% of the deaths in the city, but overall, apparently, they're underrepresented in the data.

There's a reason to question all of this data. It's just not good enough, strong data. It's really incomplete, at best and lots of caveats. But it seems to me that might be doubly true for Latinx folks. I just wonder if you could weigh in on that.

One only a handful of places, a handful of states, maybe a dozen states have actually reported racial data on who has died from COVID… Only in 35% of the cases, a third of the cases, do we know the racial identity of the person who died… There's a reason to question all of this data. It's just not good enough, strong data. It's really incomplete, at best and lots of caveats.

Andrew Grant-Thomas, EmbraceRace

Nicolás

Barceló: So, when it comes

to the data, I'll start by just saying a few things. First, as you noted in the

first slide, we don't have enough of it generally. Nationwide, 34% where race

was identified. And for communities like Native people on reservations, there's

just a tremendous paucity of data and a lot of that has to do with more than

we'll be able to discuss during the session. But it is something that we are

actively looking at in the center and examining what are the factors associated

with the outcomes on American Indian reservations.

The question specifically with regard to Latinos, the slide is interesting because it's contrasting like the percent in the area and then the percent of deaths. And I think if I read it correctly, the slide identifies Los Angeles County as having 34% Latinx. And that number, we hear so much variation on. I mean LA City; we hear sometimes up to greater than 50% Mexican. And then at UCLA, this is a problem that we've been looking into now for quite some time. And that is that our electronic medical record at times has had different defaults whereby the standard income, like “identified race” was white unless changed. And then it's like, who's changing it?

And then one of the things that you said, I caught when you said when we were talking about the white population, people who identified as white Americans, well are they proactively saying I identify according to this race or are they being identified by who knows who in the emergency room with questionable training. And so in the hospitals where I have worked, I have seen gross inaccuracies when it comes to the identification of race in electronic medical records. A lot of the results we have are coming from those places. And in very few cases has it been that the patient was identifying for themselves.

And then so with Latinos, at UCLA we're seeing a lot of Latinos who are not appropriately being coded according to race appropriately. And then I think one of the big questions that is coming up in all health services research is how do you assess the quality of data for people at the margins for whom presenting to health services is such a risky, daunting decision. And I think that time will give us a little bit more information when it comes to what's happening in the Latino community.

In the hospitals where I have worked, I have seen gross inaccuracies when it comes to the identification of race in electronic medical records… And then I think one of the big questions that is coming up in all health services research is how do you assess the quality of data for people at the margins for whom presenting to health services is such a risky, daunting decision.

Dr. Nicolás Barceló

But before I wrap up, I just want to say one other thing

and perhaps we can kind of to continue the discussion later, which is what we

do with data, what we do with numbers. I'm not saying that we don't need it,

but it's something that I would like to question and deconstruct and explore

and how to use the words of Ruha Benjamin who I

greatly admire, who said, “The numbers do not speak for themselves.” And what

do we do with the data and what kind of inquiry does it establish while we're

also questioning its validity. So let me pause there.

Chandra Ford: I don't have much to add. I do share those concerns about the limitations of the data. Clearly there are some trends there and I think for me the question is what are the trends, what is it that they tell us? Much of the data on disparities that are emerging now, as newspapers report them or as the health departments report them, they don't talk a whole lot about the missing data. So it's hard to draw a full picture, but they do still should show some kind of pattern.

My big concern is (and we're not doing this here) that the general public or policymakers or public health officials don't assume that those numbers tell us something about the people. I think they tell us something about the underlying inequalities that people and communities are managing to survive or have been managing to survive over time.

In this case, the data with Latinos, I think, is the question of who counts as Latino. I often wonder, because the white category, when we collected in our census data or our agency data, often forces people to either be Latino or white, at least when we reduced the data down. And so if that's happening, then we're under-counting the experiences of Latino folks. In Los Angeles, and actually in the state of California, there was a decision, a very good one to not support and to to really discourage ICE from getting people at hospitals and healthcare settings.

And that sounds really good, especially on the surface. But then you think about the history is that people are not caught at the hospital per se, but maybe a mile away from it, or those kinds of things. So it's a great first step, but it doesn't address the underlying insecurities, I think justifiable insecurities and concerns, that many here in LA for instance from the Latino community, might feel in terms of coming forward for a diagnosis.

And so what's concerning to me besides the fact that we don't have universal testing in our country, so we don't actually know who all is infected. But to reach the point of death, mortality, that's the final outcome. It means people have slipped through at various stages of the care continuum. And in terms of even perhaps getting care, perhaps they got there late, what happened once they were in the healthcare setting? And so death is a pretty serious indicator of problems along the entire continuum. I think it's a real red flag for us.

And so what's concerning to me besides the fact that we don't have universal testing in our country, so we don't actually know who all is infected. But to reach the point of death, mortality, that's the final outcome. It means people have slipped through at various stages of the care continuum. And in terms of even perhaps getting care, perhaps they got there late, what happened once they were in the healthcare setting? And so death is a pretty serious indicator of problems along the entire continuum. I think it's a real red flag for us.

Dr. Chandra Ford

EmbraceRace: Chandra, when you say that you worry that people think

these numbers are about the individuals and not about the underlying conditions,

do you mean when people sort of say, “Well it's about being diabetic or obese.”

And those are sort of ways that people kind of dog whistle, “It's your fault,”

rather than talking about food deserts and transportation and green space and

all of these areas that produce sort of lifestyle inequities?

Chandra Ford: Absolutely. So, there are these causes and it's easy to focus on, “Oh well you're obese.” Actually, I wouldn't say it's easy. It's not easy to do that because we relinquish our humanity when we choose to view people in those ways and to blame them in these ways because it could very well be any one of us in many of these circumstances.

So it's not the individuals, but the context in which the individuals live, or I'll put it this way. We cannot ignore the context in thinking about how the individual is affected. And I think in the current context of this pandemic, which the virus attacks the lungs, we have to think about things like how pollution happens. We can go to the environmental justice literature, which has consistently shown that communities of color, tribal communities, poor communities are systematically the places where environmental hazards are placed.

And it is precisely because they are located in those locations, not only that people who live close to them experience poor health outcomes related to those hazards, but it's also the reason why people who don't have those hazards in their neighborhoods actually live better, have better health outcomes related to those kinds of hazards.

In the current context, I think we also have to think about the relationship between those who are on the front line. I recently went to the grocery store and I saw more black people in this particular grocery store that I think I've ever seen. And I started to realize that many of them were Instacart workers and others working on the front line, putting their lives at risk so that others of us could distance ourselves from the risk of exposure. And so I think there actually is a moral, as well as an empirical, element here that if we think about the ways that certain communities or populations have higher rates of disease or higher levels of risk, we also have to think about it in ways that tie it to how the rest of us might be actually benefiting or contributing to those dynamics.

In the current context, I think we also have to think about the relationship between those who are on the front line… And so I think there actually is a moral, as well as an empirical, element here that if we think about the ways that certain communities or populations have higher rates of disease or higher levels of risk, we also have to think about it in ways that tie it to how the rest of us might be actually benefiting or contributing to those dynamics.

Dr. Chandra Ford

EmbraceRace:

Absolutely. I know one of the

things we were talking about last night is that we have undocumented workers,

in many cases, right now deemed essential workers. And so, we should have known

that before, but now officially designated essential workers, getting letters

from their employers saying as much but, at the same time, they're being deported!

Nicolás I just wanted to pick up on one thing you said about really the guesswork. Who is identifying folks? I'm thinking of some research I saw years ago really getting at the "social construction of race" showing that people I think it was morgue attendance, identifying or having to fill out paperwork, identifying the racial identity of people who don't have family members for example to say this is what they are in terms of race, ethnicity. And if the research showed that if for example, someone died of a liver condition, they were more likely to be identified as the native. If they died of homicide, they're more likely to identified as African American. So, this really pernicious use of stereotypes. “If the person thought this way, he must be that,” which is absolutely incredible.

But when we think about who's at risk or at the narrative about who's at risk, then maybe it starts with age. Age clearly does not explain in itself why people of color broadly speaking seem to be at higher risk.

Because in fact white people in this country are the oldest population, followed by Asian Americans, followed by African Americans I think, followed by Latinos. So, if age is in fact a significant risk factor [for COVID] where older people are more likely, that doesn't explain it

Can you tell us a little bit about the correspondence between underlying conditions like hypertension, diabetes and racial identity?

Nicolás Barceló: And racial structures. I think before getting to that, but as kind of part of that response, I think that one of the things that Dr. Ford was perhaps hinting at was, in addition to the ethical drivers of how we're responding and thinking about what's happening, I think that the normalization of the outcomes we're talking about, using a justification of underlying chronic physical health metrics. That normalizing process is the kind of cognitive gymnastics that I work with all the time in kind of a clinical sense where it's like, I feel some anxiety and perhaps guilt that I'm seeing something happening to another person.

Can I create or can I grab hold of a narrative that helps relieve that anxiety? And if I can just say, “Well it's because they have more chronic risk factors,” without being challenged to understand why they have more chronic risk factors, then that anxiety is relieved to a certain extent. But it's only possible if I've embraced the belief that there's something normal about people of color, before COVID ever started, suffering from and dying from all of these conditions that I'm now using to kind of offload my guilt regarding why they're dying at disproportionate rates now. Does that all kind of follow?

EmbraceRace, Andrew: Yeah. Absolutely. I mean it's always been striking, and I'm certainly not the only one struck by it, that in social sciences, certainly medicine I think, we so often talk about “controlling for”. So, if they hold constant all these things that in fact are associated with race. If you control for poverty, if you control for education, if you control for how badly people treat you. If you control for all these things, then oh gosh, race has a very small effect. But actually, the way we do race in this country, that's what it means as a lived experience. So sure, if you want to try to obliterate it by pretending it doesn't have any impact.

EmbraceRace, Melissa: And I do love that there are so many narratives floating around that people are taking hold of. Like when we were hearing first that elderly people were dying more, I turned to Andrew and I said very ineloquently, “But that's in white years. They’re talking about it in white years. Like wait a minute.”

We know they're not talking about us because it's a very real fear that communities of color are more likely to have underlying conditions and the whole thing. And I am hearing,“Oh in the black community there's so much misinformation and na na na na na.” I'm sure there's some misinformation, absolutely. But we've got a mis-informer in chief behind the podium who a lot of people are listening to. And when we talk, and and according to surveys, communities of color are in fact more afraid for their safety and health in this time of COVID. So, it's actually doesn't add up.

EmbraceRace, Andrew: And a follow-up to Melissa’s point. This idea that age and who are we talking about? What does age mean? Because of course we got the first set of data and did a lot of sort of extrapolation I think from a China case and from Italy and so on. And what we know here is that COVID does seem to have less impact on children 17 and younger. But boy, a lot of people right in that next age, 18 to 44 are getting sick.

A lot of people, 45 to 64. I haven’t seen in this analysis, but I wonder if it's not about, well some people, some groups of people are in effect aging faster because of what they're subject to. And Chandra you mentioned some environmental conditions.

Nicolás Barceló: I think what you're getting at is this weathering hypothesis, which is that the chronic cumulative stress associated with racism does certainly have an impact on health. And that operates in so many different ways because racism touches everything in the life of a person of color. And it does also in the life of white people but it's a privilege to not have to be aware of it.

Dr. Ford and other critical race theorist talk about racism as common and every day and ubiquitous. And ubiquitous is so important because it means it's everywhere. It's in every transaction and every meeting. And every place you go and every decision you make. And I think that it's something that ... this might be a digression, but that we can even reflect on in terms of COVID and the number of people for whom racism is off their radar now in COVID are having their lives so dramatically changed and they're saying, “There isn't a thing that I can do without worrying about whether or not I'm going to be infected. Or does it increase my likelihood of becoming infected? Does it make me unsafe?” And that emotional toil, that weight, I think is really affecting a lot of people. And I think that for people who have not considered the experience of a person of color, that is a glimpse of what it's like to be thinking about racism all the time when it's everywhere in your life. If I go to this grocery store, if I go to this gym, if I go to that school, if I do, will I be victimized by the racism that is taking its toll on my everyday?

And what's interesting about it is that it's like, if you get COVID, heaven forbid any of us and any person on this call does become infected, you start second guessing all the decisions you made. Oh am I responsible for ... maybe I shouldn't have gone there. Or this person who exposed me, they told me they didn't mean it on purpose. They didn't know. But you're not worried about the fact they didn't know because you're sick. And I think that that gets at, when we talk about racism, really focusing on the importance of looking at racism and studying racism through the impact that it has on people of color, independent of what people's intentions might've been. And I think that that's kind of something that we can continue to talk about. But I'll turn it over to Dr. Ford and see if you have any other thoughts.

EmbraceRace: I have to say Nicolás, I think you said just a moment ago reminded me of a conversation I had with a police chief who said, “Whatever bad thing a police officer does anywhere in the country, that gets public, it gets high profile, we get stigmatized here in my community. So, we have to deal with what police officers do somewhere else.” And I felt, wow, that sounds familiar. As you can pick up, he is a white police officer.

There are huge issues we're talking about and to turn it around, many of us were wondering, what would it take, what kind of moves would be required so that the next crisis that hits, we're not having exactly the same conversation about racialized vulnerabilities and so on. That's a very, very big question.

I'm wondering for both of you in your fields of medicine and public health. Are you seeing, or has this planted some seeds, some of which could flower into a real advance, something you're excited about? Can you speak to that a little bit?

Chandra Ford: I think there are some things we can do. I mean there are things certainly that people can do as individuals, even outside of the field. For instance, just think how many people are complaining about what it feels like to be "locked up" in our homes that we personally design and we can go to the kitchen cupboard and our dog is walking around with us. Can that help us connect to the people who are truly locked up without rights, some of whom are not even guilty and some of whom are no more guilty than people who are not locked up.

So, I think on the individual level as human beings, as people, and I know I keep going back to this, but I do think this is important and I think even as researchers and scholars, it's important for us to remember and connect to our humanity. So I think that's one thing.

We're at this moment now where people are actually talking about the R word, racism. I think it's worth noting this moment because people did a lot of work to get us to this point. So it's not just that people are choosing to say it now and they could have chosen to do it before. There has been a foundation laid in public health, outside of academia and elsewhere and people are really beginning to call out these underlying structures.

And to me that's very important because we can't actually document the problem if we can't name it. And so getting data by race and ethnicity for instance, as you showed earlier, give us the first glimpse that there is something here that we need to excavate and understand. And so those are just two things, in my opinion, that are very feasible, manageable little things that we can do right now.

There has been a foundation laid in public health, outside of academia and elsewhere and people are really beginning to call out these underlying structures. And to me that's very important because we can't actually document the problem if we can't name it. And so getting data by race and ethnicity for instance, as you showed earlier, give us the first glimpse that there is something here that we need to excavate and understand.

Dr. Chandra Ford

EmbraceRace:

We keep seeing this thing

about that crisis and opportunity is two different sides of the same coin. Are

you seeing some opportunity in this?

Nicolás Barceló: Absolutely and I can't help but also briefly being distracted by the questions [in the chat]. There's a question about, can we call out racism for what it is in this systemic inequity? And I think that what academics and advocates and public health officials to varying extents across the country are trying to do is look at the way in which racism has become systematized and operationalized within our institutions. And a number of ethicists, including again going back to Ruha Benjamin, and some folk who are working in Dr. Ford’s center have begun examining even in medicine, systematically how has decision making from an ethical viewpoint been codified?

And if it's been codified such that people who have the best chance of surviving be given the resources to ensure that survival because they were triaging people, we are always going to be shifting resources away from people of color, women, the disabled, et cetera. And we'll be shifting them towards more affluent white men who are able bodied and more likely to be high educated and high income. So that is one example of a way in which the processes and the way medicine operates, reflects a decision that had become so standardized as to be perceived as like the inevitable natural truth of how things should be.

And that's because it serves the interest and benefit and health and longevity and comfort of those who have control of how the system is being operated in the first place. But that's not necessarily the case. And I think that people like Dr. Camara Jones who again is kind of collaborating with a number of us, have already laid out different ways of looking at how decisions can be made and how resources should be allocated to reflect a different reality, a reality that is defined by processes that move us closer to serving those according to their need rather than to reinforce their privilege. So, I think that that's one example.

Community Q & A

EmbraceRace: The root of equity. So, a question that came in previously from Tracy asks, can you talk more about the link between COVID and environmental racism and how black and brown people and indigenous folks are faring?

Chandra Ford: The short answer is we don't actually have the data on that. And I would really urge public health officials and especially policymakers in thinking about the next big bill to come through to require that data are available to look at those kinds of connections. Well we have some preliminary data. For instance, I know some of my colleagues here at UCLA have documented what looks like trends.

But when we talk about this it's like, we already know that pollution causes breathing difficulties for instance like asthma and other respiratory conditions. And so to have people disproportionately affected by these sorts of respiratory conditions also impacted by this pandemic. And then because the respiratory conditions are not just happening in places that are otherwise similar socioeconomically, but they have these other forms of disadvantage, like residential segregation, that mean that these things are going to be compounded. Thinking about it in terms of the relationships epidemiologically, it looks almost like a nightmare to think about rolling out, to have folks with high rates of respiratory conditions being targeted by or being exposed to a virus that targets the lungs and then to be in a place where there are fewer healthcare providers potentially or other resources. I mean it's like a health professionals' nightmare.

Thinking about it in terms of the relationships [between COVID and racism] epidemiologically, it looks almost like a nightmare to think about rolling out, to have folks with high rates of respiratory conditions being targeted by or being exposed to a virus that targets the lungs and then to be in a place where there are fewer healthcare providers potentially or other resources. I mean it's like a health professionals' nightmare.

Dr. Chandra Ford

Nicolás

Barceló: There's this

confluence of factors, which is kind of this perfect storm. Where, as Dr. Ford,

you mentioned that people of color are more likely to live in places where

there are high levels of air pollution, where there is housing with higher

levels of mold for example, which are going to increase risk of respiratory

conditions. We know that epigenetics and stress can change the expression of

certain physiology in the lung that would then also complicate things like

asthma.

And we know that these communities are taking, like we said, the Instacart jobs at greater rates. And I think that all of those factors together really should caution us from interpreting what we were, going back to earlier, how communities are perceiving the risks of COVID. And making assumptions about people's desire to stay at home or shelter in place and their capacity to shelter in place. Because if you don't have an income unless you leave your home to work, then your thoughts around COVID are immaterial. And I'm seeing this here on the West side of LA and it's kind of boggling my mind because I'm seeing my neighbors buy up the entire Sprouts and Whole Foods and they got all the toilet paper and then I go for my walk around the block and there is an unmasked Latino gentlemen mowing your lawn.

And I'm like, “You can hear him, he's out there! Pay the man and tell him to stay at home.” It probably wouldn't cost you that much. You could afford to pay your gardener his month's salary and just tell him, “Don't worry about my lawn this month, stay home,” which you can. He can't stay at home if his money is dependent on that yard. So there's this again, this cognitive dissonance where it's like the preoccupation that some are feeling to protect them own selves, but then normalizing it when it's the exposure or risk of others.

EmbraceRace: That’s a really crucial and basic point about sheltering in place. When you think about the assumption there. The assumption clearly, I mean yes it's a great idea for those of us who have a safe consistent place where we can shelter. But if you think about homeless populations, you think about incarcerated populations. So, you have some jurisdictions who are releasing some nonviolent offenders because they cannot have six feet among the people who are behind bars. You think about multi-generational families and who tends to be in those.

I'm seeing my neighbors buy up the entire Sprouts and Whole Foods and they got all the toilet paper and then I go for my walk around the block and there is an unmasked Latino gentleman mowing your lawn. And I'm like, “You can hear him, he's out there! Pay the man and tell him to stay at home…” He can't stay at home if his money is dependent on that yard. So, there's this again, this cognitive dissonance where it's like the preoccupation that some are feeling to protect them own selves, but then normalizing it when it's the exposure or risk of others… If we can't implement some of the things that we're talking about in terms of moving towards equity, we're more likely to have a growth in inequity that would then continue to compound over time.

Dr. Nicolás Barceló

Nicolás

Barceló: Populations

without access to indoor plumbing, migrant farm workers. I heard recently that

there's this discussion about reducing the AID funds that are sent to countries

that don't accept back asylum migrants. And it's just mind boggling because

ultimately this could be a shock to our system that if we can't implement some

of the things that we're talking about in terms of moving towards equity, we're

more likely to have a growth in inequity that would then continue to compound

over time.

Chandra Ford: When I think about what this moment offers us, that is what I think. That it is a moment, when we can choose equity. We can choose to really be in it, like we're all in it together. Right now, when I hear people say that, it feels very superficial to me. Like we're all in this together. It's like yeah, we are, but some of us are sitting at the top of the ball and some of us are kind of underneath the ball.

Nicolás Barceló: We haven't been in this together at all before this started. So, to say that we are now.

EmbraceRace: Chandra you a few minutes ago mentioned the racial data and of course we talked about the need be much better at that. And also while being very critical of what exactly we're seeing and how is it collected, who's deciding who's what, those sorts of things. We have a few questions about really sort of where and when, is the collection of this data [on race] mandatory in hospitals by health departments and these sorts of folks are reporting it out. Is it just a complete hodgepodge? Is it state by state? Is it actually municipality by municipality? Are people talking about making it mandatory? Can you give us some little insight on that?

Chandra Ford: I can. The short answer is yes, it is hodgepodge. And I'll give the case study of LA. The LA County Department of Public Health, the Director, Barbara Ferrer, you all might be familiar with her, has done a phenomenal job with the LA Department of Public Health. And they mandated that people report race and ethnicity data when they do testing and so forth. But a lot of private entities and other groups are just doing the work and then saying, “Well we don't have the time, we're overburdened so we're not going to record data on race and ethnicity of patients.”

And she [Barbara Ferrer] considers that to be something that is not acceptable, but yet difficult to try to enforce. And so I have a lot of concerns about this because there is this sort of, in particular under the particular the Trump administration, the sense that, “Well we just have a bunch of companies, they do some testing and a test as a test and that's it.” And in terms of quality control, both of the disease-related testing and information but also of the demographic and inequality related information is a big issue in my opinion. So I think we need to do some political mobilizing around that to try to get Congress or our local officials to regulate that better.

EmbraceRace: And we certainly have gotten a lot of questions about how to talk to kids about COVID especially how to talk to kids about the disparity, especially if your child is in a targeted group. That's something that we've sort of thought about as well as because it’s scary, to hear that black people, that Latinos are more much more vulnerable.

Chandra Ford: Well, I think it's important to remember that it's not that there's something about the group. It's really about the way the virus is traveling through our society. So, there's nothing about a specific group, even thinking about age. It's not that at 64.9 [years old], a person is fine and then suddenly 65 everything's out the window. It's really, I think it's useful to think about these as, you know, they give us information about the overall ways that the virus affects us.

So as people age, they have more chronic conditions, they're more susceptible and those kinds of things. And so I think it's important for children to ... actually if we were to think about it categorically, children are like the least at risk. But I think it's better to simply think more in terms of the ways that the virus travels and affects populations.

EmbraceRace: What do you think the legacy of this crisis be? Do we come together and recognize systemic racism's effect on health outcomes for people of color and others? Or do we all dig into our corners and just exacerbate health disparities?

Chandra Ford: Oh my, that's a zinger.

EmbraceRace: I think it's really about is this going to be more of the same? On one hand this is certainly a huge moment for more of us than we're accustomed to. So, when we had the ‘07 ‘08 recession people said, gosh it's a recession for much of the country. So, our assessment for Black America was already a recession. I mean the depression for Black and Brown America for example, for Native America. Now everyone, of course it has everyone's attention. More people certainly are appreciating the structural vulnerabilities we're talking about and how racialized they are than perhaps it's ever been true with, ever had occasion to see. Not to say that everyone's aware and not to say that everyone frankly cares, but more people do.

So is this a moment where do you ... and this is just sort of subjective, what are you hearing? What are you feeling perhaps among folks you work with, patients you may have spoken to. Is there a sense of you know what? Maybe this pandemic has purchase on some folks in a way that it didn't before. The kinds of issues and concerns that two of you have. Is that true or are we actually going to be fine. The people who are better situated to survive it in all sorts of ways will do that and then go back to what they were doing and thinking before or might we actually turn a little bit of a corner here?

Chandra Ford: Not bubbling over with optimism.

EmbraceRace: It's hard to bubble over. Isn't it?

Chandra Ford: Actually, there are several different things that might seem unrelated that inspire me. One, is there are sometimes been attention, especially thinking about the West Coast and LA, California between the focus on racism that for instance African Americans and Latinos may raise and the experiences of some Asian American populations. And recently in part because of the ways that Mr. Trump racialized this pandemic, this is an opportunity where Asian American, African American and other racial ethnic minority groups are actually seeing difference and similarity and coming together and coalitioning.

So I think that's a really important milestone and opportunity in terms of moving beyond just this pandemic, how we can relate to one another in ways that grow a movement in that way. I'm optimistic even though I think there are many reasons not to be. We live in a capitalist system where there has to be the sort of surplus labor, you know, people at the bottom that we are fine exploiting for their labor over time.

And so, sadly if we allow the ones who are already here to not survive this pandemic, then that means ... that places others of us who are in the mainstream at risk for becoming the new lower rung of the ladder. So, I think even if only motivated by our own self-interest, that many of us will work to try to preserve, to try to keep more people protected than not. That sounds very cynical, doesn't it?

Nicolás Barceló: No, I think that my take is to ... One of my coauthors, Sonya Shadravan who's a peer here in the Department of Psychiatry at San Francisco, or excuse me, Los Angeles. I went to medical school in San Francisco guys, talks about is how racism is mercurial and transforms with time. And I think that what we've seen, if we look at the history of the United States, is that racism takes on a new face as the society in which it's playing out changes.

And so the question of will we see more of the same? No, in terms of how racism manifests, but will we see racism continue in new forms? Likely.

Because that's what we've seen up until this date, right? I think that the question of what can be done or to what extent we can feel hope, I think that part of the answer is in questioning the willingness of people to continue to face tremendous discomfort which would be associated with the loss of privilege that, prior to COVID, made life comfortable for some people and very uncomfortable for other people.

Because James Baldwin, he said when people ask him about change and he's saying, how much longer do I have to wait? Because when I was a young man, you said just wait, wait, wait. We're changing, we're transforming and then I was a middle aged and it's just wait, wait, people are transforming and now I'm old and I'm tired of waiting. And if we're saying that we want change but we also want it to be comfortable, we're just going to keep waiting. No matter how timely it may feel in the light of an acute process, the change will be much longer.

And so only if we're willing to abandon the privilege that we have as beneficiaries of this racist and capitalist and misogynist and colonialist system, may we then have that chance. And it will be uncomfortable. And so that's kind of where I am.

EmbraceRace, Melissa: What we're trying to do with Embrace Race is we’re trying to raise a brave generation when it comes to race. And that's where I see hope, is just trying to raise kids who actually see what they see as opposed to being taught they don't see what they see. So, there's a sliver, but we really appreciate what you guys are doing and you having this conversation with us. Thank you.

EmbraceRace, Andrew: Nicolás Barceló and Chandra Ford, thank you so much. One of the things, Chandra as you said earlier, death is sort of the final outcome for too many people indicative of all kinds of lapses, shortfalls along the way. Which is to say there's a lot more going on beyond who dies, as critical as that is. And we see the disparities there.

We are so thankful and appreciative to the two of you for

sharing your expertise. There are so much more we could have talked about, but

you shared a lot of great stuff. Thank you.

Thank you for the work. And to be continued. Take good care.

Resources

George Floyd’s Autopsy and the Structural Gaslighting of America, Scientific American, 6/6/20

The COVID Tracking Project. “The COVID Tracking Project is a volunteer organization launched from The Atlantic and dedicated to collecting and publishing the [racial and ethnic] data required to understand the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. Since early March, 2020, we have grown from a tiny team with a spreadsheet to a project with hundreds of volunteer data-gatherers, developers, scientists, reporters, designers, editors, and other dedicated contributors.”

Nicolás E. Barceló

Chandra Ford