Watching my Five-Year-Old Wrestle With His Whiteness

By Shannon Cofrin Gaggero

A BLM sign my 5-year-old made for a local protest

I am a white woman, married to a white partner, raising two white children, ages 5 and 3. For the past several years, I’ve followed the lead of organizations like EmbraceRace and Raising Race Conscious Children who are educating and empowering parents to ditch the “I don’t see race” approach to child rearing. Instead, I’ve learned to talk about race explicitly and often with my kids.

Research shows that children notice racial differences as early as infanthood. We also know that not speaking about race with young children does more harm than good. We live in a culture rooted in white supremacy, so when kids are left to make sense of race by themselves, they often develop biases their own parents may not share.

Because of his age, I’ve talked more openly with my 5 year old about the violence that accompanies racism. After Charlottesville, I shared what happened, albeit in vague terms, and asked my son if he had any ideas on how we could respond as a family. He thought for a moment, and said, “why don’t we buy 100 Black Lives Matter signs and hand them out to people walking down the street?”“I like that idea,” I responded. “Maybe I can reach out to our friends and neighbors and see who would like a sign. Can you help me think of what to say?”

“Sure!” he said. “How about, ‘who wants a Black Lives Matter sign like ours?’” Last year we placed a gorgeous, yellow Black Lives Matter sign created by Black artist Matice M. Moore in our home’s window.

Organizing the BLM signs for distribution

This kind of conversation is pretty typical in our house. When we talk about race and racism or problem-solve ways we can advocate for justice, I am the one to prompt and frame these discussions. My son surprised me last week, however, when he recognized his whiteness and its accompanying privilege for the first time on his own.

My son tends to select a new favorite book every week. I can never predict which title will catch his fancy, but we will read one book again and again, for several days in a row, until his focus changes.

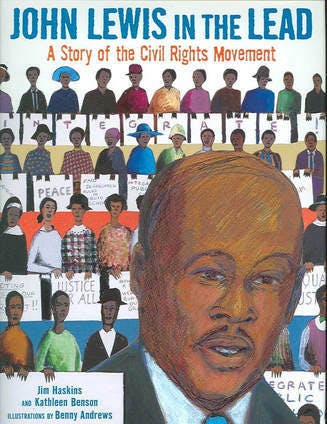

Last week, the book of choice was John Lewis in the Lead: A Story of the Civil Rights Movement, by Jim Haskins and Kathleen Benson. We live in Atlanta, Georgia, and John Lewis is our congressperson, which I think adds an element of excitement and interest for my son.

The book does not hold back on the injustice of Jim Crow laws or the brutality civil rights protestors experienced at the hands of the police and white citizens alike. My son will often comment, “that’s not fair!” in response to segregation and has a lot of questions about the violence inflicted by police officers. But the discussions during our readings overall remained surface.

However, after our second or third day of reading John Lewis in the Lead, the conversation shifted. My son grabbed my arm in the middle of the story and said in a panicked voice, “Wait a second. We’re white, right Mommy?”

“Yes, honey, we’re white,” I responded.

A look of relief washed over his face. We were at the point in the book that describes segregation and the injustice Black people faced.

“So we wouldn’t have had to sit on the back of the bus or not go to certain restaurants, right?” my son questioned.

And there it was. My son’s first glimmer of understanding into what it means to be white and racially privileged. He was expressing relief that his whiteness would have protected him from the horrors of Jim Crow. This was the first time he drew the connection between his skin color and preferential treatment without my help.

“You’re right,” I affirmed. “Because we’re white we would have been treated differently. White people are still often treated better than Black and Brown people today. Do you think that’s fair?”

“No, but I would NOT want to have to sit in the back of the bus or not be able to get a library card,” he said adamantly.

“I understand. I wouldn’t want any person or law telling me where I could sit, or eat or go to school, either. But that was the reality for Black people fifty years ago and in many ways the unfairness continues.”

“That’s why people say ‘Black Lives Matter’, right?” he connected.

“Yes, ‘Black Lives Matter’ points out that Black and Brown people are hurt by police more than white people. And that needs to change.”

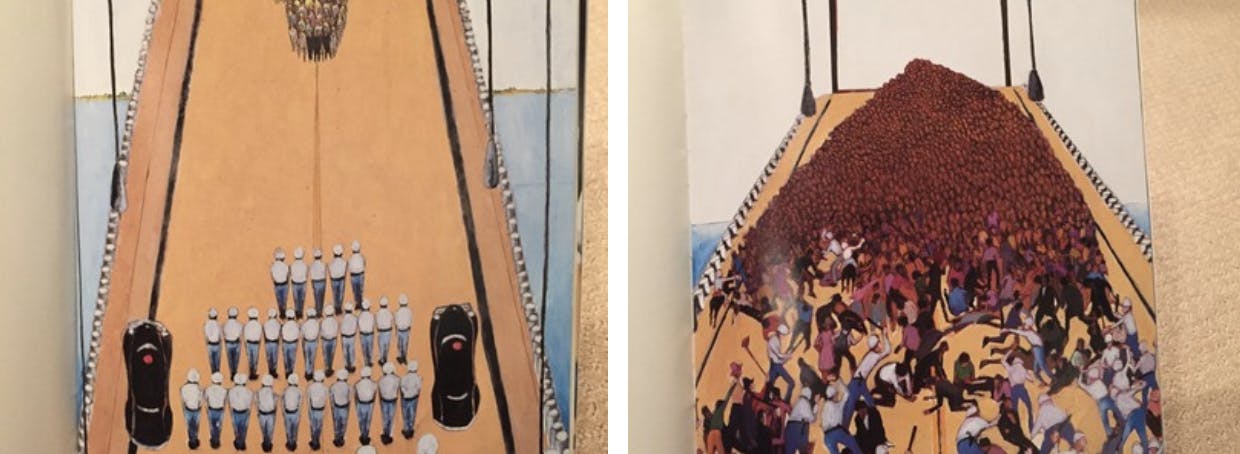

We kept reading until we reached the part about “Bloody Sunday” on Edmund Pettus bridge. The images in the book are very powerful, showing a sea of protestors facing off with police officers. There is also a picture of the protestors being attacked by police and civilians.

My son touched my arm again, gently, and asked, “why did the white police officers and people hurt the Black people? We’re white and we don’t want to hurt Black people.”

And now my son was grappling with another part of whiteness: the violence and oppression we’ve perpetuated.

“I don’t understand it either,” I said. “I guess they were scared to lose power. Their fear filled their hearts with hate and they made horrible choices and hurt a lot of people.”

“I don’t like this part of the book,” he concluded.

“Witnessing people being mistreated is really hard,” I agreed. “But it’s important to remember, for as long as Black and Brown people have been treated badly in our country, there have been people who have been standing up and saying ‘this is not right!’”

“Yeah, like John Lewis and Dr. King,” my son said.

“Yes, and Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, and Black Lives Matter activists today!” I added.

His little body seemed to relax.

“We are white, as you named earlier. We do get a lot of benefit from being white, even though we didn’t ask for it and we can’t help that we’re white,” I explained. “Our job is to notice and say ‘no!’ when we are treated differently because of our skin color. Our job is to join the people fighting for justice.”

“We helped spread out Black Lives Matter signs in our neighborhood!” my son said.

“Yes! And you thought to do that, remember?”

“Yeah!” he said, proud.

“You also suggested we host a lemonade stand and donate to Black Lives Matter Atlanta. Maybe we can do that this summer?” I asked.

“Yeah, and we can invite our friends!”

“It’s a plan,” I said. We finished the story and got ready for bed.

I’m reflecting on many things as I process what we discussed. The experience hammered home talking about skin tone and naming race must happen first; without this context, my son and I could never have gone this deep.

I’m also struck by both the relief and shame he discovered as he self-identified as white. I can totally relate, as I imagine many white people can too. He was relieved to know he wouldn’t have been treated badly, then felt extraordinary sadness by the fact white people hurt Black people. This paradox perfectly encapsulates whiteness.

Finally, I’m reflecting on the fragility born within whiteness, particularly as it relates to what we’re willing, or rather not willing, to discuss with each other and with our children. White people often accuse me of robbing my children of their innocence by educating them about the historical and modern day effects and realities wrought by racism. White parents often share the fear over loss of innocence prevents them from speaking about race with their kids.

I don’t look back on this interaction with my son as a loss of innocence, but rather a moment of truth telling. Was he disturbed? Yes, the history is extraordinarily disturbing. Was he confused and perhaps even overwhelmed as he reckoned with his own whiteness? Absolutely. But I’m here to attest he made it through the experience okay. Empowered, even.

People of color must share our country’s history and perpetuation of oppression with their children as a means of survival; it’s a privilege to opt out in the name of preserving innocence. White children can and should shoulder this knowledge alongside children of color. We impede progress when we aren’t even willing to educate and arm our children with the truth.

There are many lessons I hope to teach my children about what it means to be white. I hope to teach them to not look away from injustice even though we can; to reject the comfort our white skin privilege affords us; to confront the violent legacy of whiteness; to constantly battle our own internalized white supremacy; to let go of the shame and focus on action; to lift up, listen to and follow people of color. The work towards justice is happening all around us. After reading Mia Birdsong’s beautiful Lift Up the Freedom Fighters: Why Resistance Must Be Part of Any Discussion of Oppression, I also want to make sure our children understand people who are oppressed have always fought for their liberation and continue to do so.

I know this is a lot for my little ones to learn. Lord knows I have just as much learning and unlearning ahead of me, too. But I take comfort in the fact it will be a family affair.

Shannon Cofrin Gaggero

Get Insights In your Inbox

Join our community and receive updates about our latest offerings - resources, events, learning groups, and news about all matters race and kids in the US.

Subscribe