Wanting to Give the World to My Children

Or, How it Felt to Send my Black Son and Daughter Abroad this Summer.

By Megan Dowd Lambert

The author and her family on daughter Tayja’s graduation day. Photo credit: Linda Dowd Lambert

When I was nervous about sending my oldest son, Rory, to preschool, I came across a quotation, attributed to writer, Elizabeth Stone, that captured a feeling I’d had since becoming a mother but hadn’t been able to articulate: “Making the decision to have a child — it is momentous. It is to decide forever to have your heart go walking around outside your body.”

Her words acutely described the vulnerability I felt in loving another person so fiercely that I made bargains with the universe about his safety and well-being: “Throw anything at me. I can handle anything that comes my way — except losing this child or having something terrible happen to him.” This was the sort-of-prayer, or exercise in magical thinking, that I indulged in as a young mother determined to protect Rory and guide him safely and whole through his life and into adulthood.

It is not enough to prepare our children for the world; we also must prepare the world for our children

Luis J. Rodriguez

Of course, healthy development requires that children grow up and away from parents’ protectiveness and guidance, and that’s where the vulnerability captured by Stone’s quotation comes in. In my case, it was compounded by the knowledge that racism and White supremacy pose threats to Rory’s safety and well-being as a biracial Black person.

When parents of children of color send our kids out into the world, we know our hearts are “walking around outside our bodies” in spaces that often aren’t safe for their hearts and their Black and Brown bodies. We strive to give them all the tools we can to help them stay safe and whole, as we simultaneously work to dismantle racism and counter White supremacy. In the words of Luis J. Rodriguez: “It is not enough to prepare our children for the world; we also must prepare the world for our children.”

A screenshot of the author skyping with her son, Rory, during his trip to South Africa with the UMass-Amherst Grahamstown Festival course. Photo provided by the author.

I’m well past the stage of sending Rory, now twenty-years-old, off to preschool, and while I have tremendous confidence in the young man he’s become, I admit I still worry about him as he makes strides that bring him farther away from my protection and guidance. On a literal level, this distance placed him thousands of miles away from me this summer after he completed his second year in college and travelled to Grahamstown, South Africa on an academic program to attend the the world’s second-largest theater festival.

Although I was sending my two, Black, eldest children abroad at the same time, I quickly realized that they needed very different things from me to support them in preparing for their experiences.Rory had travelled internationally before — to Germany and Canada with me when he was a little boy and my only child, and more recently to his father’s homeland of Jamaica. But his eighteen-year-old sister, Tayja, who came home to our family as an adoptee just before her eighth birthday and who is also Black, had never left this country.

This changed when she graduated from high school in June of this year and went on a month-long “Japanimation” trip to Japan through the Experiment in International Living. She had long professed a desire to visit Japan to explore her passion for manga and anime and to build on the knowledge she’s acquired about the culture through karate classes and independent inquiry, and this seemed like just the right opportunity.

It may sound a bit cliche to say that I want to “give the world” to my children, but supporting them in taking these trips felt on literal and figurative levels like I was doing just this. This satisfaction didn’t come without worry, and as I reflect on the matter, I know I had deeper reservations about sending Tayja so far away.

One thing I’ve learned as the mother of six children (as of this writing I am pregnant with my seventh child) is that a great deal of parenting involves adapting to the individual child’s needs, strengths, and challenges. In other words, what works with one child won’t necessarily work with another in terms of serving their best interests and supporting their growth and development. Although I was sending my two, Black, eldest children abroad at the same time, I quickly realized that they needed very different things from me to support them in preparing for their experiences.

The author’s son, Rory, with his UMass-Amherst Grahamstown Festival group in South Africa. Photo provided by the author.

Rory is a fiercely independent person who’s quite savvy, particularly about how others regard him as a young Black man. Tayja, on the other hand, is young for her age and is in no hurry to grow up. This is true, in part because of the instability of her early years, and with regard to race, I think it’s fair to say that she is as naïve as Rory is worldly.

This all means that I often find I need to dial her emotional age back in my mind when I consider what she’s ready for and how to best support her growth and development, and I’m fiercely protective of her in ways I’m not about her sisters and brothers. It’s a consistent challenge to balance that protectiveness with pushing her to take the steps I know she must in order to achieve independence and healthy growth and development as she becomes an adult.

I am well-aware of how young Black girls and women are perceived in this country as hyper-sexualized and older than their actual ages, and I worried that this perception could follow her in Japan, where I wouldn’t be present to help her navigate any negative situations that might arise from these stereotypes.

It follows that I was much more hands-on with helping Tayja prepare for her trip than I was in helping Rory prepare for his. On the practical side of things, I helped him a little bit with application paperwork, and I dipped into his 529 college savings account to cover the expense of the trip. But he took the lead in most other preparations, rejecting my repeated, motherly offers of help with shopping and packing and such, and he made all his own domestic travel arrangements.

On the other hand, I spent hours helping Tayja with her application and scholarship paperwork. I helped her go through all the program materials about what to expect during the month-long stay in Japan. My husband booked her domestic flights and I repeatedly reviewed her travel itinerary with her. For her part, since this wasn’t a credit-bearing program I couldn’t use 529 funds to pay for the trip, so although we chipped in on the program fee and airfare, Tayja happily turned over the bulk of her earnings from her part-time job, and she wrote out thank-you cards to the dozens of friends and relatives who sent graduation money that helped make up the difference.

When it came time to pack, I took her shopping, and I was firm about the program’s packing-list advice that she bring “modest” clothing out of respect for Japanese cultural norms: mid-length shorts, no tank tops, no clothing that was too revealing or tight, because such items were “frowned upon.” Tayja wasn’t pleased — especially about the no tank tops rule for a summertime program. But I wouldn’t budge, not just out of respect for the cultural norms named in the program’s preparation documents, but also because my protectiveness reared its head.

I am well-aware of how young Black girls and women are perceived in this country as hyper-sexualized and older than their actual ages, and I worried that this perception could follow her in Japan, where I wouldn’t be present to help her navigate any negative situations that might arise from these stereotypes.

If “modest” clothing could help mitigate such circumstances, I’d stand firm about the packing guidelines, though I admit I didn’t like the implicit message that how one dresses is to blame for how one is treated.

The author’s daughter, Tayja, when she earned her yellow belt in karate in 2014. Photo credit: Megan Dowd Lambert

I also thought a lot about how traveling to a homogeneous non-Black society could impact her, and so I started trying to talk with Tayja about how she might respond to remarks or interactions about race, her Blackness, our unconventional multiracial, adoptive, blended, queer family structure, and so on, while in Japan.

For example, while she currently wears her hair in micro-braids, at the time she had dreadlocks, and I asked her how she’d feel if people started touching her hair or commenting on it (a concern a Black colleague of mine raised almost immediately when I told her about Tayja’s plans). It’s not like this couldn’t or hadn’t happened in the U.S., but I wondered how she’d be regarded and treated as one of very few Black people, and one of fewer with dreadlocks, in a Japanese community, and if this would exacerbate the potential for such encounters.

“I wouldn’t care about that,” she said.

“But what if it happened a lot?” I wondered, recalling this video about “how microaggressions are like mosquito bites.”

“I don’t know,” she replied, employing a standard rejoinder for times when she doesn’t want to talk about a given topic anymore. So, I wrapped things up by affirming that it’s always ok for her to tell someone not to touch her hair, and I respected her wishes in that moment to stop the conversation.

This felt quite different from talking with Rory about anticipating his trip, in part because it would immerse him in a majority-Black environment, and in part because throughout his life, we’ve had fascinating, probing, deep, and sometimes difficult conversations about race, gender, sexuality, history, politics, and power. I knew his program would explicitly nurture and guide his thinking about and exploration of these elements of identity and society, and I was excited for him.

Tayja’s comparative reticence in our conversations is a familiar part of her reserved and introverted personality. She’s always said she likes her privacy and doesn’t like talking about her feelings, and I try to be understanding and accommodating of how she differs in these ways from her older brother. I can recall many times when she’s shut down a conversation instead of opening up.

When she was about ten-years-old, for example, I made one of many attempts to talk with her about puberty, menstruation, and sexuality. While Rory reveled in such conversations to the point that I’d sometimes pull back a bit from his questions and disclosures to maintain my own privacy and healthy boundaries, that day Tayja listened dutifully, but was silent. I closed by stressing that she could always come to me, about anything, and I told her I loved her and wanted her to feel safe, supported, and informed.

“So do you have any questions?” I asked her.

“Yes,” she replied, and I could almost feel my ears physically opening up wider to receive every little syllable of whatever question she was about to pose. And then she asked,

“Is this conversation over?”

As funny as that moment was, I knew then, as I do now, that I can’t let Tayja’s reserved nature, nor her naivete, totally preclude us from having necessary conversations about puberty, sexuality, race, and more. Nor can I, as her White mother, pretend I have all the knowledge and experience necessary to provide her with everything she needs as she grows into Black womanhood. Her relationships with other people, including Black teachers, mentors, peers, and friends, are vital, too.

The author’s daughter, Tayja, with her Japanimation group in Japan. Photo provided by the author.

And so, as we prepared Tayja for the Japanimation program, I was happy to confirm that The Experiment values diversity in its recruitment of student participants and trip leaders. When I brought her to a pre-trip orientation we found out that her trip leaders were White, but we also learned that the student group was a diverse one, including several Black students and other students of color from across the country.

Past participants on trips around the world, including two Black students, spoke about their experiences in India, Serbia, and other countries, including the enduring relationships they’d made with their host families. I felt myself relax a little, growing more comfortable with the plan to send my daughter so far away from home as trust built inside of me about the diverse group itself, and about the program’s vetting and recruitment of trip leaders and host families.

Left: The author’s son, Rory, visiting a children’s center in Soweto, with his UMass-Amherst Grahamstown Festival group in South Africa. Photo provided by the author. Center: The author’s daughter Tayja at a festival in Japan, wearing an outfit her host family loaned her. Photo provided by the author. Right: The author’s daughter, Tayja, arriving at the airport after her trip to Japan. Photo credit: Sean P. Lambert St. Marie

In the end, both Rory and Tayja had the time of their lives on their respective trips. Rory returned bubbling over with stories about the amazing performances he’d seen, the affirming experience of being in majority-Black spaces, and the sense of belonging and camaraderie he felt when the large Rastafarian communities he encountered there greeted him like a long-lost, dreadlocked brother.

Tayja showed me hundreds of pictures she’d taken in temples, museums, and at festivals she attended, and she showered her siblings with gifts she’d bought for them in Tokyo.

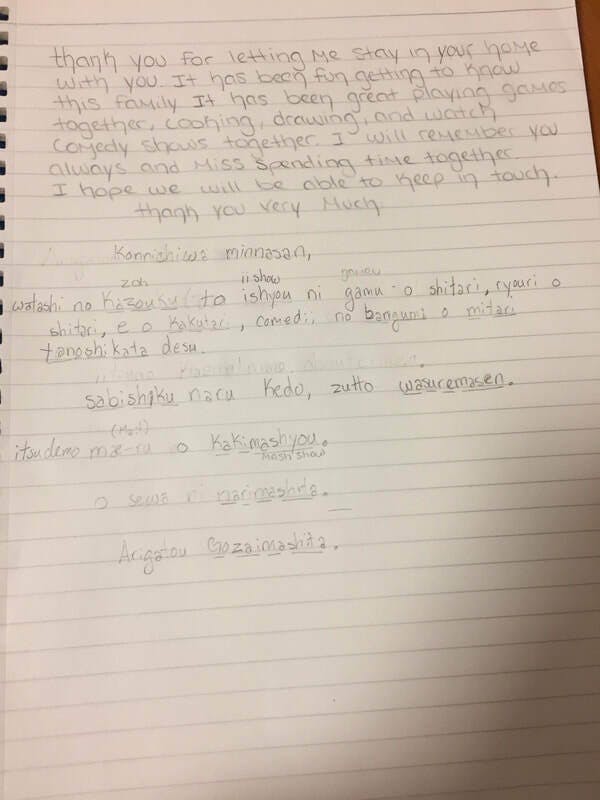

She also shared the speech she gave, in Japanese, to thank her host family, explaining that someone had written out her English words in phonetic Japanese, and I marveled at the bravery it must’ve taken for my shy daughter to stand up in front of the room and read it out loud. She proudly told us her manga instructor said she had “good technique,” and in a rare display of emotional vulnerability she fell into my arms and wept when feelings of letdown about her trip’s end consumed her.

The speech the author’s daughter gave to thank her host family in Japan. Photo provided by the author.

My worries and concerns about sending Tayja so far away and into circumstances where I couldn’t protect her or help her work through any potential racial microaggressions, or worse, ended up being largely unrealized.

Her host family couldn’t have been warmer or more welcoming, and she felt accepted by and engaged with her peers. “My host mother cried when I read my speech,” Tayja said. When I asked her if she’d experienced any moments of cross-cultural confusion or misunderstanding, she said her host family was surprised when she said she “didn’t really have a religion,” though she told them we do celebrate holidays like Christmas and Easter. And in a different conversation she made an offhand remark about how (American) participants on her trip couldn’t say her name so they called her “Deborah.”

“Why couldn’t they say your name?” I asked. “They’d never heard it before, I guess,” she replied and then said she thought it was “hilarious” and “random” that they called her Deborah. I bit my tongue against the impulse to say how this sounded unfair to me since I didn’t want to redefine my daughter’s experience for her.

But I chafed at the story and recalled the “My Name My Identity” campaign I’d heard about when I was teaching Alma Flor Ada’s chapter book My Name is María Isabel, about “a Hispanic child growing up in the U.S., [who] begins having problems in her new classroom when her [White] teacher changes her name to Mary.” The novel explores how this misguided, flippant decision silences and shames María Isabel, and how finally speaking up and reclaiming her name is a moment of great import for her as she asserts her identity as a Hispanic child.

But this wasn’t Tayja’s experience when her peer (a non-Black teenager of color) started calling her Deborah and the rest of the group followed suit, and ultimately, it’s not up to me to decide how my children define their experiences with race, racism, and microaggressions, or worse. I do, however, take seriously the responsibility of preparing them for the realities of growing up in, and heading out into, a world where, as Cornel West famously put it, “race matters.”

Was I worried ..? Of course. Did my heart break ..? Yes. But, I also know that wholly protecting them from the realities of racism is impossible and would ultimately endanger them more so than confronting it and guiding them in doing the same.

Two of the author’s daughters at the Solidarity with Charlottesville vigil this summer. Photo credit: Megan Dowd Lambert

Soon after my children returned home from their trips abroad, the violent, White supremacist “Unite the Right” rally took place in Charlottesville and our president equated Nazis and KKK members with those who bravely counter-protested, saying “I think there is blame on both sides.” Rory was among the thousands of people who participated in the resistance march and counter-protest against the so-called “Free-Speech Rally” that followed in Boston a week later. The rest of us were away on vacation that week, so we found the nearest Solidarity with Charlottesville vigil we could and attended it.

Was I worried about Rory? Of course. Did my heart break that my other children witnessed a few people giving us the finger, and yelling obscenities and lines like “Build the wall!” as they drove or walked by the vigil we attended? Yes. But, I also know that wholly protecting them from the realities of racism is impossible and would ultimately endanger them more so than confronting it and guiding them in doing the same.

As flawed as it is, I do want to give the world to my children. The flip side is that as I see what individual, strong, good-hearted adults they’re growing up to be, I want the world, here in our little corner and far afield, as well, to see how lucky it is to have them walking around in it.

Megan Dowd Lambert