Too Much Or Not Enough? Racially Socializing My Black Daughter.

By Sandra (Chap)Chapman

Racial socialization involves the implicit and explicit ways that families convey their own views about race and racism to their children. At times, these messages are purposely delivered to bring affirming language and pride to one’s racial group and to protect against the child’s inevitable encounters with racism. At other times, these messages are unintentionally delivered after a racialized moment.

Racial socialization among African American parents has been found to be a primary way parents assist children in coping with racial bias, instilling racial pride, and contributing to their children’s self-esteem. Can too much preparation be harmful?

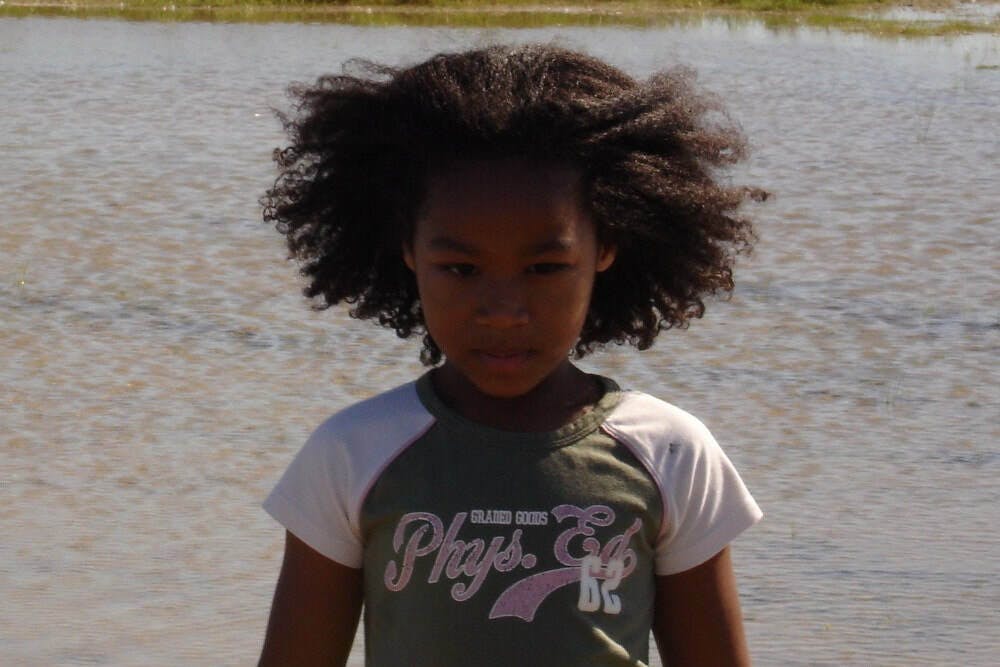

As a medium brown-skinned Afro-Latina, raising a bi-racial daughter of African American, Dominican and Puerto Rican descent, I wanted to do all I could to help her feel proud of her many ethnic groups, collective cultural heritages, and the black and brown communities to which she belongs. In addition to the photos of her and her family framed everywhere around the house, we read children’s books with positive images of Black girls, Latina girls, and children of color of any gender, age, and ability. (For more ideas see #weneeddiversebooks).

A practice that caused some controversy for my family was my hard and fast rule that she only receive and play with brown-skinned baby dolls, preferably with no hair, but if there had to be hair it had to resemble her kinky tight curls. Despite my “rule,” my daughter received her first peach-skinned Barbie doll from a friend for Christmas when she was six. The next peach-skinned baby doll came from a relative. By the time she was seven she had as many brown-skinned dolls as she had peach-skinned dolls. Every time she reached for a doll that did not resemble her skin tone, I made a frustrating groan and comment about the impact of her choices. My biggest concern was how was she going to feel great about her skin if she chose to play with a doll who had a skin tone she would never have, and came with skin privileges she would never experience.

I couldn’t help but recall the images from the 1940s Kenneth and Mamie Clark “doll test,” whereby they found that Black children not only preferred the white doll to the black doll, but a majority of the Black children associated positive characteristics and words with the white doll. The 2005 documentary, A Girl Like Me, replicated on a small scale the Clark study, and found that a majority of the Black children still preferred the white doll over the black doll. That film was produced five years after my daughter was born and around the time when my intentional racial socialization began to increase.

I learned that there were ways my messages about racial pride would help my daughter develop positive self-esteem and protect her from internalizing the racism already shaping her experiences. However, I also learned that an overemphasis on preparing her for bias could potentially leave her feeling helpless. This feeling of helplessness against racism would negatively impact her overall sense of self. Within six more years, my daughter would be an adolescent. I did not want her to encounter racial bias and feel that she could not protect herself; I wanted her to feel she had a voice and could be proactive around racism.

I had to acknowledge that her thinking about, and experiences with, race and racism were limited. At seven she was still a concrete and factual thinker; so, what I said about White dolls and, by association, White people, could inform how she reacted to White people she didn’t know. I worked on how I would change my messages to represent a better balance between racial pride and preparing for bias.

About this time my daughter began to ask for long flowing hair similar to her Asian and White friends at school. I interpreted this as both her wish to experiment with her image and a slippery slope most parents of girls with kinky hair encounter. I saw this as a moment to engage in racial pride. I explained the science of hair, talked to her about our African-, European-, Taino-heritage to explain why Latinos have such variety of hair textures, and re-read our favorite books like Hairs! Pelitos! and Nappy Hair.

We visited the African hair salon in our Harlem neighborhood to see the options for a girl like her. I told her that companies created chemicals for hair like hers in order to make it look more like straight hair, but that I was against this for her. I set that boundary, but promised we could return to hair straighteners when she was old enough to understand the consequences. We then discussed the possibilities for the flowing hair she wanted, and she agreed to have her hair braided, and the following year locked.

To address the doll situation I brought my daughter to three different toy stores — a local shop in Harlem, a big toy store in midtown, and a toy store in a predominantly White neighborhood.I wanted to point out a common issue found in each of the stores: the brown-skinned dolls were either absent from the aisles or tucked behind the peach-skinned dolls, and there were far fewer than the peach-skinned dolls. We also noticed that we could not find dolls like some of her friends — no almond-shaped eyes, no glasses, no head scarves. Using this experience as a catalyst we had further conversations about my worry that she would eventually not want to play with dolls that looked like her when stores were already pushing her to consider dolls that did not resemble her features.

Navigating the racial terrain leading up to her adolescence was a full-time job. A visit to the museum to view women’s fashion through history yielded a question from her about the existence of Black women in history and the likelihood that Black women would not have worn such clothing. By this point she had a rudimentary understanding of the enslavement of African people and was connecting the dots between this history and the stories she encountered elsewhere.

At twelve she began to babysit for younger children. She came home one day to report that things hadn’t changed much. I asked her what she meant. She shared that she and her little brown-skinned charge could not find a doll like them at the toy store. We laughed together when she explained that she mimicked me by moving boxes of peach-skinned dolls to the back in order to bring the brown-skinned dolls to the front. This was my attempt, and now hers, to create a different experience for the next child who entered the store. I explained to my daughter that this was a small act, but it was rooted in the ways Civil Rights leaders and everyday sheroes took action in the past to benefit people for a future they may not see.

My 16 year old daughter is proud of so many aspects of her identity. She still has a long road ahead of her — college, the workforce, family making (if she chooses). In the meantime, we continue to talk about racial moments she is navigating. I want her to know I will always be around to help her process race, racial pride, and racism. It is an aspect of parenting that I take most seriously.

Sandra "Chap" Chapman