“They’re Not Too Young to Talk About Race”: The Science of Early Racial Learning

by Christina Rucinski, from EmbraceRace's 2023 Reflections on Racial Learning

The budding field of children’s racial learning is deeply rooted in the science of child development. Mounting evidence demonstrates that children are noticing, processing, and making meaning of race early and often, beginning in infancy — long before they are walking and talking.

Many parents, educators, and other caregivers have a very different understanding. They believe that young children are “innocent” about race: that they do not notice racial differences like skin color; that they are totally unbiased; that they do not perceive the meanings, values, and stereotypes attached to racial identity in the world; that teaching and learning about these difficult topics are best deferred until children are older. By delaying conversations about race and racism, caregivers believe they are helping preserve children’s innocence.

Yet a 2020 research study showed that adults generally underestimate how early children start to notice and process race. 1 On average, their estimates are off by about 4.5 years. The research literature shows us that children begin to distinguish faces by race early in infancy 2 and that racial biases are often formed by the preschool and kindergarten years. 3 Plus, the age at which adults think children are capable of processing race influences when they are willing to engage children in conversations about race. Recent studies suggest that the average adult believes that a first conversation about race should occur around the time children turn 5 years old. 4

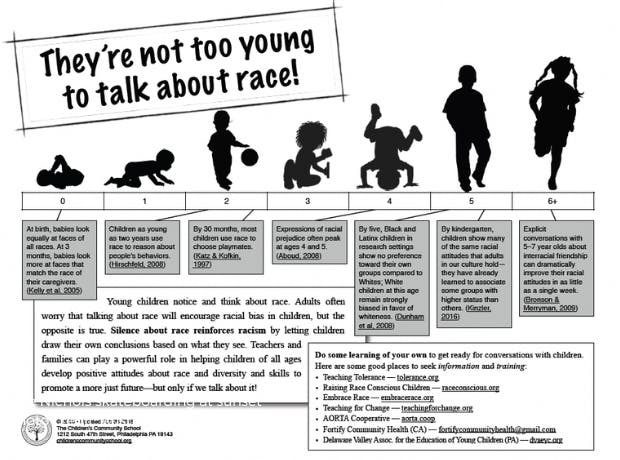

The reality is that young children are learning about race whether or not their caregivers talk about it or believe the learning is happening. The extraordinary popularity of a graphic shared by the Children’s Community School of Philadelphia in 2018 suggests growing awareness that children begin to notice skin color and develop racial preferences and biases early in life.

(This graphic blew up on EmbraceRace’s social media. Twice. The widely-shared timeline is reprinted here with permission from the Children’s Community School of Philadelphia.)

The early development of racial ideas and attitudes, including racial biases, does not mean that biases are innate and unavoidable. Instead, it shows how children come to interpret race as a meaningful social category based on many inputs from their environments. For example, in racially homogeneous environments, infants generally prefer looking at and are better able to recognize faces that match the race of their caregivers. Babies regularly exposed to racially diverse faces show no racial preference. 5 Unfortunately, most children in the U.S. experience caregiving environments that are racially homogenous.

Children are keen observers, paying attention to patterns they notice in the world around them, and forming implicit theories about why those patterns exist. This helps explain why children’s racial preferences come to reflect status differences in society by about 3-4 years old. By this age, White children generally show clear pro-White biases, while children of color do not show similar preferences for their own racial groups, and often show preferences for higher-status groups over lower-status groups. 6 During these early years, children pick up both explicit and subtle messages about which groups of people are most and least valued and privileged in their society, and quickly internalize those ideas. 7 From who is portrayed as a hero on TV and whose story matters, to which neighborhoods people live in and what jobs they have, to who gets “in trouble” most often in school and who takes which classes – messages about race are coming at children from all angles.

Thus, from very young ages, children are learning about race whether or not we are intentionally talking to them about it. When we don’t actively guide children in making sense of these patterns — specifically, anti-Blackness, the devaluing and dehumanization of people of color, and the high value ascribed to whiteness in U.S. society — we leave them to draw their own conclusions. In this case, they are more likely to internalize messages from other sources that suggest these inequities are deserved.

When we don’t actively guide children in making sense of these [racial] patterns — specifically, anti-Blackness, the devaluing and dehumanization of people of color, and the high value ascribed to whiteness in U.S. society — we leave them to draw their own conclusions.

But if we take the opportunity to engage children in conversation over these many incoming messages, as well as providing counter-messages and counter-examples, caregivers and communities can help children understand the patterns they observe as products of racism, unfairness, and structural barriers, and not deserved, justified, or unchangeable. 12 We can pair messages about the world we would like to see — in which all are treated equally and fairly regardless of race and where we celebrate our common humanity — with honest recognition that in the world we live in right now, people are treated unfairly based on the color of their skin. It is okay for both adults and kids to have strong, negative emotions about that. It is also important to talk together about what we can do to change it.

It makes sense that many adults, especially but not exclusively White caregivers of White children, feel uncomfortable or anxious talking about race with children. We are often unpracticed ourselves at having race-based conversations. We might worry about causing unnecessary stress or ruining our children’s innocence. 8 The emerging field of children’s racial learning is grounded in the reality that even young children are already noticing and making sense of race; in the belief that teaching and learning about race can be entirely — as in, 100% — developmentally appropriate at any age; and in the conviction that our own behaviors and the choices we make for our children’s environments matter as much as the words we use.

Children are capable of understanding complicated topics if we break them down into simpler terms, like differences in skin color and how people look; fairness and unfairness; true and untrue stories people tell; and how people are treated. Kids are capable of handling big emotions if we give them space, strategies, and support to process those feelings. Children don’t need us to be perfect and tell them all the answers; what they really need is for us to ask them questions and listen to their answers, and to model the ability to say “I don’t know” and admit when we have more to learn.

Our children are ready to learn about race. And the earlier we start talking about it, the more opportunities we have to practice and learn along with them.

This article comes from the introduction of Inaugural EmbraceRace Reflections on Children's Racial Learning. Download all the reflections from leaders attending to children's racial learning in parent practice, education, healthcare, children's media and social science research.

References

- Sullivan, J., Wilton, L., & Apfelbaum, E. P. (2021). Adults delay conversations about race because they underestimate children’s processing of race. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 150(2), 395-400.

- Kelly, D. J., Quinn, P. C., Slater, A. M., Lee, K., Gibson, A., Smith, M., ... & Pascalis, O. (2005). Three-month-olds, but not newborns, prefer own-race faces. Developmental Science, 8(6), F31-F36; Kelly, D. J., Quinn, P. C., Slater, A. M., Lee, K., Ge, L., & Pascalis, O. (2007). The other-race effect develops during infancy: Evidence of perceptual narrowing. Psychological Science, 18(12), 1084-1089.

- Dunham, Y., Chen, E. E., & Banaji, M. R. (2013). Two signatures of implicit intergroup attitudes: Developmental invariance and early enculturation. Psychological Science, 24(6), 860-868; Raabe, T., & Beelmann, A. (2011). Development of ethnic, racial, and national prejudice in childhood and adolescence: A multinational meta-analysis of age differences. Child Development, 82(6), 1715-1737.

- Sullivan et al., 2020. See also forthcoming 2022 EmbraceRace Parent Survey. A research study conducted in partnership with Breakthrough Research, with contributions from research service providers Prodege, Forsta, and California Survey Research Services (CSRS).

- Anzures, G., Quinn, P. C., Pascalis, O., Slater, A. M., Tanaka, J. W., & Lee, K. (2013). Developmental origins of the other-race effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(3), 173-178; Bar-Haim, Y., Ziv, T., Lamy, D., & Hodes, R. M. (2006). Nature and nurture in own-race face processing. Psychological Science, 17(2), 159-163; Heron-Delaney, M., Anzures, G., Herbert, J. S., Quinn, P. C., Slater, A. M., Tanaka, J. W., ... & Pascalis, O. (2011). Perceptual training prevents the emergence of the other race effect during infancy. PloS One, 6(5), e19858; Kelly et al., 2007.

- Dunham et al., 2013; Hailey, S. E., & Olson, K. R. (2013). A social psychologist’s guide to the development of racial attitudes. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(7), 457-469.

- Dunham, Y., Baron, A. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2008). The development of implicit intergroup cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(7), 248-253; Olson, K. R., Shutts, K., Kinzler, K. D., & Weisman, K. G. (2012). Children associate racial groups with wealth: Evidence from South Africa. Child Development, 83(6), 1884-1899; Shutts, K. (2015). Young children’s preferences: Gender, race, and social status. Child Development Perspectives, 9(4), 262-266.

- See, for example, Bañales, J., Marchand, A. D., Skinner, O. D., Anyiwo, N., Rowley, S. J., & Kurtz-Costes, B. (2020). Black adolescents’ critical reflection development: Parents’ racial socialization and attributions about race achievement gaps. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30, 403-417. ENDNOTES Reflections on Racial Learning, 2023 45.

- Vittrup, B. (2018). Color blind or color conscious? White American mothers’ approaches to racial socialization. Journal of Family Issues, 39(3), 668-692; Wu, D., Sánchez, S., & Perry, S. (2022). “Will talking about race make my child racist?” Dispelling myths to encourage honest White US parent-child conversations about race and racism. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101420.

Christina Rucinski