The Wedge of Race Based Privilege

An Inter-Racial Marriage After the 2016 Election

By Divya Kumar

In the darkness of the very early morning of November 9, 2016, my husband and I lay awake in our bed. By 3 a.m., we realized that neither of us would sleep again that morning, and we turned to each other and began talking. During those fraught early morning hours, we cycled through grief, anger, numbness, disgust, and then back through them again as many of our worst fears about our country became much more real.

My white husband cried at the now all-too-real prospect of nuclear conflict and of our now ten-year-old son and his peers going to war. Stunned, I replied, “You’re worried about THAT?” While nuclear war seemed much less far-fetched than it had the previous day, it was nowhere near the top of my list of immediate concerns. Rather, as a woman of color, I feared that overt acts of racism and hate crimes would be perpetrated close to home in our progressive, left-leaning Boston neighborhood.

When I explained this to my husband, he replied, “You’re worried about THAT? That won’t be an issue here. I don’t think you need to worry about that.”“No,” I said. “You’re wrong. Hate crimes will happen here. Everything that is just below the surface will come out. Just wait.”

He said, “Yeah, I just don’t see that as the real issue here.”

In the early morning hours, as the light slowly crept in around the cracks in the window shades, I lay in bed next to the man I had been with for nearly twenty years and married to for twelve. While we had discussed differences in our race-based privilege and life experience countless times, for the first time, I felt a specific distance between us that was created by those differences. We hadn’t always agreed or seen things the same way, but we had usually found common ground or agreed to disagree and has been able to move on. But what if agreeing to disagree, especially about issues around race and privilege, was no longer acceptable to me?

As a brown woman who is the child of Indian immigrants, I’ve been the target of racism ever since I can remember. Being aware that I am vulnerable to racist comments and gestures at any time—from the glaringly overt to the subtle and seemingly invisible—is part of my existence and as familiar as the various nuisances of day-to-day life like taxes, broken umbrellas, long lines at the post office, and traffic jams during rush hour. I know no other existence besides the one in which I am perpetually exposed to racism.

My husband is an ally and a strong advocate for racial justice. In the 20 years that we have been together, though, my husband has rarely, if ever, witnessed me experience racism in real time with his own eyes. While he has heard my stories and shared rage over various racist incidents I’ve sustained (from street harassment to online parenting group debacles), he has never endured the countless questions and remarks like, “Where are you from?” “No, where are you really from?” “Why do you worship the statues?” “Do you have to have an arranged marriage?” “Does your boyfriend like smelling onions during sex?” I am always aware of the palpable tidal wave of racist remarks and acts that are barely held back by an invisible dam of socially acceptable behavior; perhaps my husband is rather blissfully unaware of what lies, visible to me, just beyond that dam. Without the awareness that is synonymous with my existence as a brown woman in this country, perhaps it makes sense that my husband would have different fears and a different idea of what is possible and real.

During the weeks and months that followed the election, that difference in perceived reality and perceived danger was highlighted in many conversations about race and racism I had with white folks. Before the election, I would often soft-pedal with white folks and take a more indirect approach, saying “I see hear what you’re saying, but the other side of it is…” whereas I now found myself getting more angry, expressing my anger in a volatile way, and saying things like, “The problem with white people is that you needed Trump to realize that America is racist when you could have just listened to people of color. If you had listened to us, you wouldn’t be so shocked right now.”

After one particularly vitriolic outburst at a gathering of friends at our own kitchen table, my husband said to me after our friends had gone home, “I know all of this is really important to you, and of course it’s important to me too, but when you start shouting at people, it doesn’t build bridges. We are a country of people shouting at each other right now, and we have to be better than that, especially now.” I thought, “As a woman of color, aren’t I entitled to my anger and outrage? Aren’t I entitled to feel betrayed by white America, including my white friends and peers?” My husband’s and other people’s expectation that I swallow my anger and speak “constructively” invalidates and erases my lifetime of experience with racism at the hands of white people.

So I asked him, “Who is WE here?”

When you are part of a marriage and a family, you can get used to being WE. WE parent our kids. WE manage our finances. WE celebrate holidays. So much of what we do as a family is done together, as a collaboration, as a synergistic process, but being a target of racism is not something that my husband and I experience as a WE. While we do have different roles and responsibilities in our family unit, I am the one who daily takes on the burden of experiencing racism, a role that was now highlighted for me in the wake of the election. Compounding this burden is yet another burden of explaining an essential piece of my existence to my husband: that ever since I could remember, I knew that racism was everywhere and could appear at any time, whereas he had the choice of whether or not to believe me and whether or not he could see my reactions as valid and acceptable. He could choose whether or not to believe my truth, and that choice right there was the wedge of white privilege between us. While I had always known this to be a reality of our relationship, the election underscored how his privilege impacted what we experienced as WE.

While my husband and I had discussed our differences in race-based privilege at many points in our 20-year relationship, these differences now created a chasm that left me feeling isolated, alone, and like the person I trusted the most could not truly understand the lens through which I view the world. In this post-election environment, when I craved safety and comfort, having this space between us was unprecedented and deeply lonely. My husband is the person whom I trust most deeply, who I know will stick by me through anything, who HAS stuck by me through many dark times, who whispered, “You are so strong,” as I pushed children into the world. During this time of heightened vulnerability, I wondered if despite our past closeness, did this chasm of privilege mean that the person whom I trusted the most was not truly on my side and could never really be?

Furthermore, if my husband and I have this wedge driven into our stable, strong, intimate relationship, what does that mean for the other relationships that I as a woman of color have with white folks in my life? If I feel isolated and separated from the person I love the most, how do I truly trust other white folks, including friends, co-workers, and community members?

Around this time during the late fall and winter, I started getting emails from other women of color who are partnered with white men and were feeling distance and isolation in their relationships because of the heightened race-based tension following the election. Most emails were a torrent of emotions and frustration and nearly always included, “I know you will understand, and he just doesn’t.” These women of color partnered with white men from different corners of my life were searching for each other, turning to each other, hoping to confide in someone who understood this wedge that had always been present but was now more forcefully driven into their partnerships due to a lack of shared lived experiences around race and racism. During this time of racial tension when people of color felt especially vulnerable to attacks, many of us suddenly felt alone in our most intimate relationships because our partners did not have the experience of walking in our skin and our bodies.

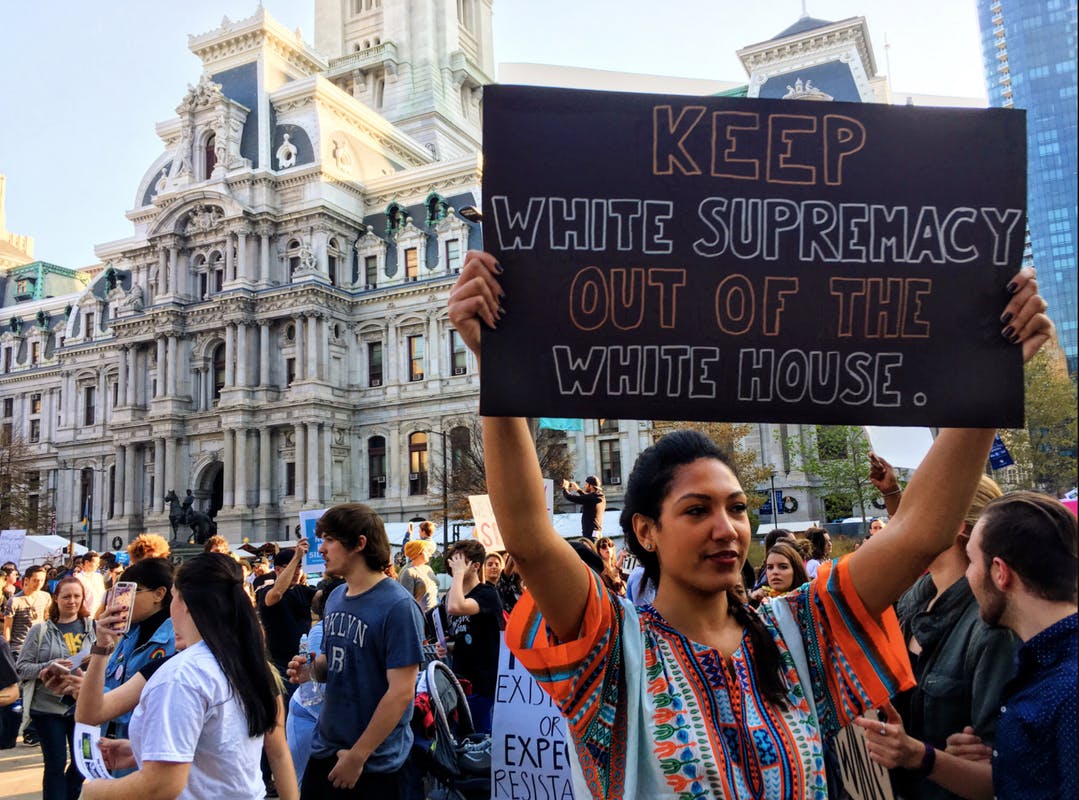

Nearly a year later, as Puerto Rico is alone and without power, white supremacists have marched in the streets, and swastikas and confederate flags have been seen in my neighborhood, this President’s mark is visible throughout the country. While I had anticipated that this presidency would wreak havoc on our government and our laws, I did not foresee the effects that it would have in my home and in my marriage. And for other women of color who feel similarly, what does that mean for how we move forward within white spaces? How are we supposed to explain our existences, build bridges, communicate “constructively”, and move forward together? How can we swallow the bile of anger and betrayal that has been in our mouths since last November?

As I reflect on possible answers to these questions, I am reminding myself that healing and building trust take time, and my husband and I are exploring what WE means in regards to our respective burdens and roles in creative positive change. The burden of reaching, teaching, and changing the people who voted for this President should not fall on me or other people of color; rather, this is/should be my husband’s burden and the burden of other white people. I have sought and created safe spaces for people of color to share concerns about what this presidency means for our relationships, children, and families since many of us are navigating unchartered ground during a time of heightened tension and vulnerability. While I don’t have perfect answers about how to close the gap between my husband and me, I am more comfortable expressing my anger and fear, and he is more comfortable hearing it, holding it, and validating it. That exchange in and of itself feels like a key part of slowly but surely un-sticking the wedge of this presidency in our marriage.

Divya Kumar