Addressing Racial Injustice with Young Children

By Marianne Celano, PhD, ABPP, Marietta Collins, PhD, and Ann Hazzard, PhD, ABPP Illustrated by Jennifer Zivoin

Our guests for this conversation were the three child and family psychologists who collaborated to write the children's book, "Something Happened in Our Town": A Child's Story About Racial Injustice. Published by the American Psychological Association's Magination press, the book follows a White family and a Black family as they discuss a police shooting of a Black man. The book includes many resources for parents and educators including child-friendly definitions, sample dialogues, and discussion guides.

In this conversation, authors Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins (whose name is misspelled in the opening video slide, sorry Marietta!) and Ann Hazzard present excerpts from the book and discuss how parents and caregivers can spark conversations about racial injustice and child empowerment with young children. And of course they take questions from the EmbraceRace community, people like you! Below, you'll find an edited transcript of the conversation - the community Q&A starts half way through - followed by a list of resources shared in the chat and then by our special guest bios.

By Marianne Celano, PhD, ABPP, Marietta Collins, PhD, and Ann Hazzard, PhD, ABPP, Illustrated by Jennifer Zivoin. Written for 4-8 year olds.

EmbraceRace: Thanks so much for being here, Marianne, Marietta and Ann. We're going to let you show us this book and tell us how you came to write it together. Then we'll talk about it a bit before we take questions from the community.

Marianne: We're happy to be here. I'll start! The book that we wrote together is called Something Happened in Our Town: A Child's Story about Racial Injustice. It was illustrated by Jennifer Zivoin.

Dr. Marianne Celano

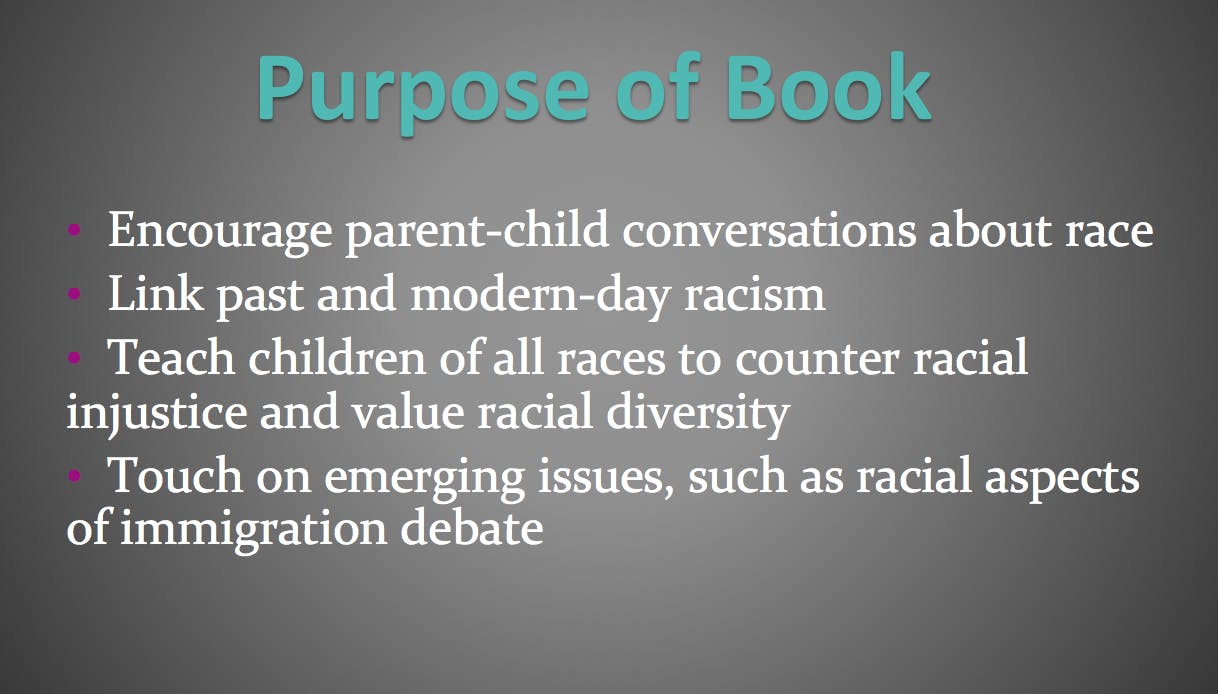

Marianne: The purpose of the book really is to encourage parent-child conversations about race. We want to link past racism, like the history of slavery and segregation and so forth, with modern day racism like racial profiling and other things. We want to teach children of all races to counter racial injustice and value racial diversity in their lives as young children. The book is really developed for children 4 to 8. So we're talking about a population of young children here. And we also want, in the book, to touch on emerging issues like the racial aspects of the immigration debate. So if you've read the book you know that the children apply the lessons that they've learned to the exclusion of a new immigrant child in their classroom at the end of the book, which we'll show you.

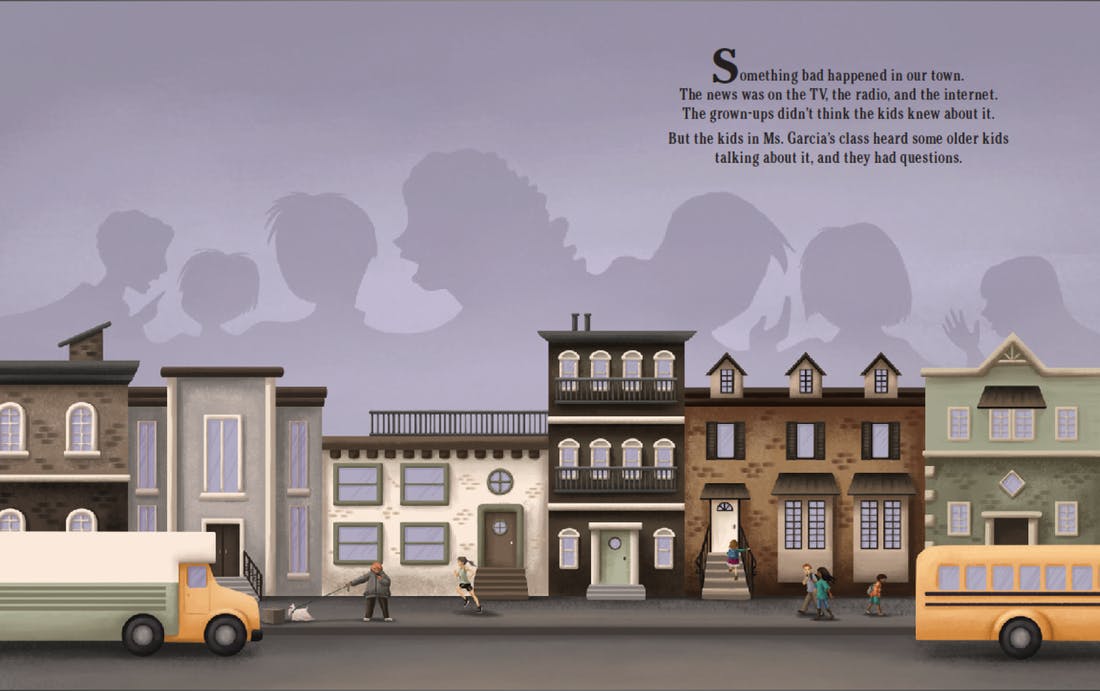

"Something Happened in Our Town" Scene 1: Kids Hear Talk About A Police Shooting

Marianne: So this is the first page of the book after the cover page. So we get right into it. It starts with a police shooting. We decided to take a very direct approach.

"Something bad happened in our town. The news was on the TV, the radio, and the Internet. The grownups didn't think the kids knew about it but the kids in Miss Garcia's class heard some older kids talking about it and they had questions."

Because we feel like this is the reality of kid's lives today. They hear other kids talk about and they have questions. And I love how the illustrator integrated both the urban scene with the school bus with the sort of shadows of people talking in the background here.

Marianne: The police shooting is a starting point for our book. We believe that police shootings represent modern day racism. Kids hear about police shootings and other incidents of racial violence and they have questions and emotional reactions. And it really is adult's responsibility to help kids understand their social world and cope with direct and indirect trauma.

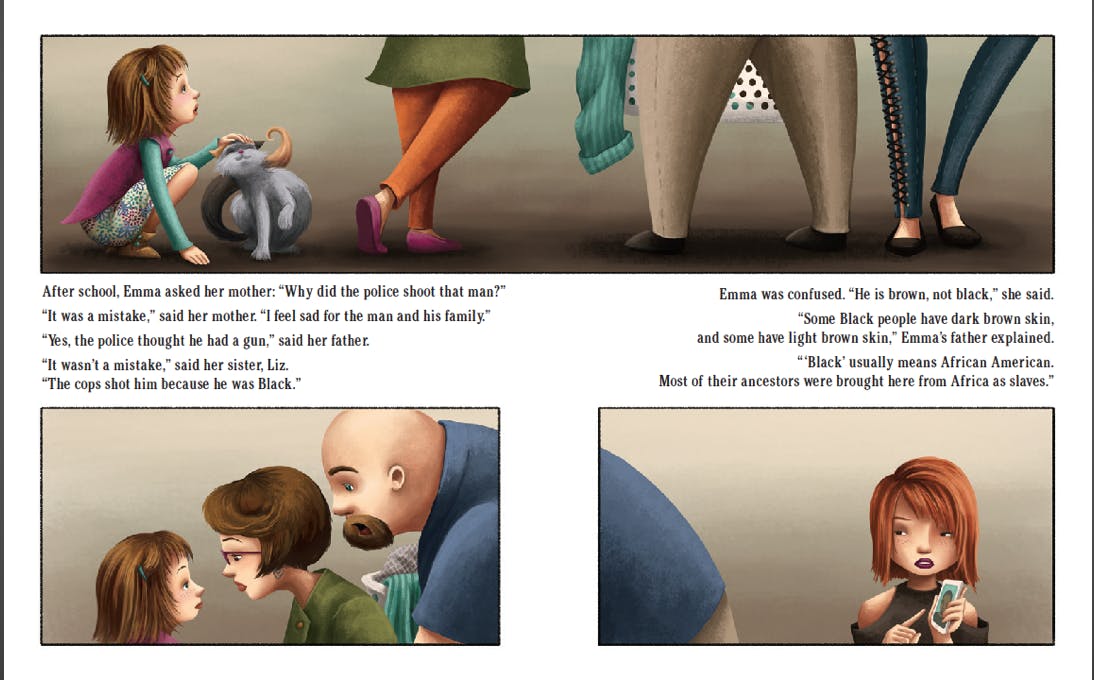

Scene 2: Young Emma Talks with her White Family About the Shooting

Marianne: So we start with the perspective of a white family. There's two main characters in the book. Emma, who's white and Josh who is black.

And here we have Emma after school asking her mother, "Why did the police shoot that man?"

And her mother's response: "It was a mistake. I feel sad for the man and his family."

And then you see the subsequent discussion. The sister saying, "It wasn't a mistake. The cop shot him because he was black." And you see the older sister in the lower right hand corner pointing to the picture of the victim on her phone.

And then Emma being confused about the term "black" and how they describe that and how they define that for her. They talk and the mother says, "Black usually means African-American. Most of their ancestors were brought here from Africa as slaves."

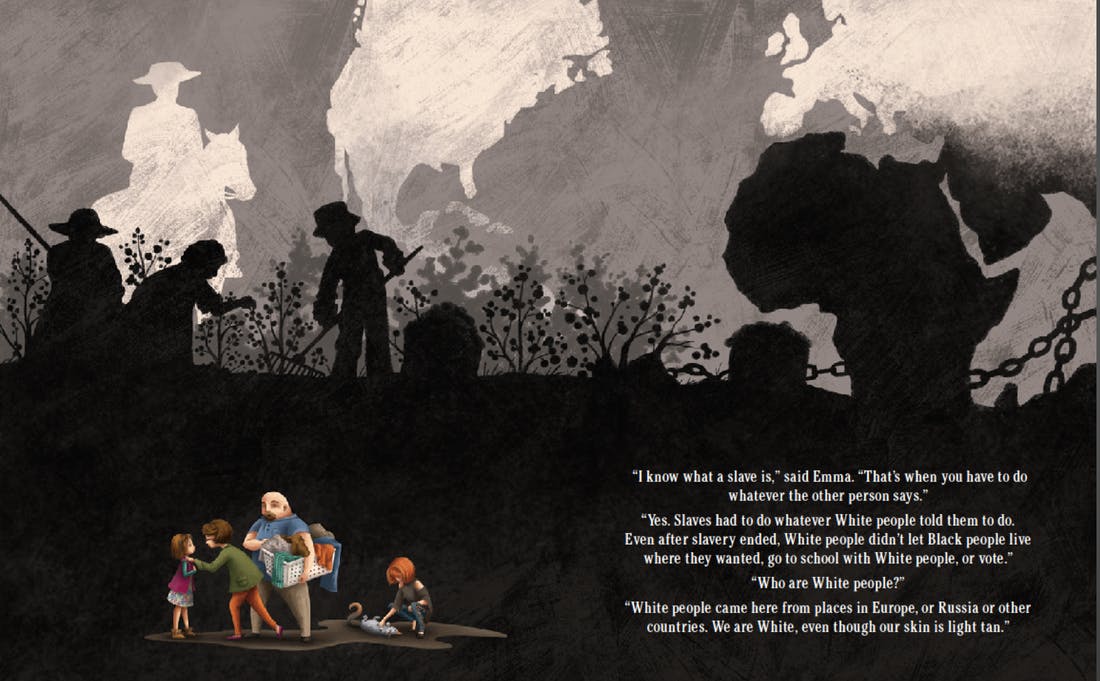

Marianne: And then Emma's reaction: "I know what a slave is. That's when you have to do whatever the other person says."

And then her mother, "Yes slaves had to do whatever white people told them to do. Even after slavery ended, white people didn't let black people live where they wanted, go to school with white people, or vote."

And then Emma's inevitable question, "Who are white people?" And then the mother's explanation. I want to point out that the illustration tries to convey several things. That the continuation of the family discussion in the inset picture but also history in the background and continents to give some historical depth to the concept.

Marianne: So the core content so far is that the police shooting is a mistake. We introduce the concept of race, talk about history, the history of slavery, give examples of biased beliefs. The point here and this part of the book is to point out that racism is an unfair pattern and we use that word a lot. Fair and unfair. We give peer exclusion as an example of bias and injustice in subsequent pages, both for the white family and the black family. And we introduce the concept that diversity adds value. You never know who is going to be your best friend.

Scene 3: Young Josh Talks with his African American Family About the Shooting

Dr. Marietta Collins

Marietta: So I'll take it from there. Good evening, everyone!

The next section of our book looks at the shooting by the police officers from the perspective of an African-American family. And here we see Josh for the first time. Josh is sitting here, as you can see in the picture, just drawing a picture of a police officers seeming to be in deep thought about something. So he takes the picture to his mom and begins the conversation about the police shooting.

He says, "Can police go to jail?" And his mom says, "Yes. Why do you ask?"

And he goes on to tell her about the white policeman who shot the black man: "Will he go to jail?"

And Mom says, "What he did was wrong."

One thing that was really important to us in the depiction of the characters in our book is that they look like children and not like mini adults. And as the African-American author [the other two authors are White], it was really important to me that the characters look like actual African-Americans - you can see the natural hair the mom has.

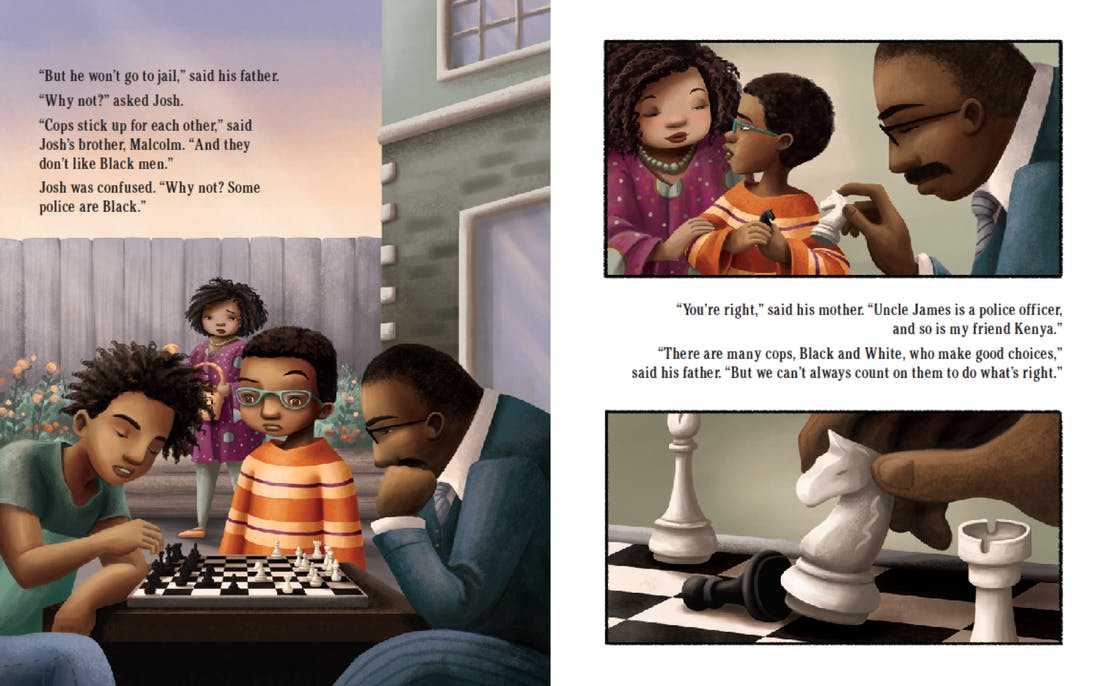

Marietta: Next, we see Josh's family, Josh is with his mom, dad and his older brother, Malcolm. And they're continuing to talk about this police shooting.

"But he won't go to jail," said his brother.

"Why not?"

"Cops stick up for each other," said Josh's brother, whose name again is Malcolm. "And they don't like black men."

Josh was confused. "Why not? Some police are black."

And mom of course says, "You're right." Because there's an uncle, Uncle James. You know he's a police officer and so is her friend Kenya.

"There are many cops who are black and white who make good choices," said the father. "But we can't always count on them to do what's right." We thought this was really important to add to the story. There are nuances that are hard for kids to see. Parents need to encourage them to not be "black and white," to look beyond that. All cops aren't all bad. All cops are not good. And we do in fact have relatives and friends with cops but we can't count on cops to always do what's right.

Marietta: And a few pages later in the book, we see Josh's father really reaffirming him so he can feel good about himself and develop a healthy self-esteem.

"I have power," Josh says. "And I'm smart."

His father smiles and says, "You're right."

And his mom says, "You can change people's hearts by sticking up for someone who's not being treated fairly."

And here we see, Josh who wears glasses, "Like how Malcolm sticks up for me when the kids tease me about my glasses. He tells them to step off."

So what we're do here again is affirming Josh's sense of healthy self-esteem and how important it is for him to know that he can stick up for people who are teasing or making unfair statements in the same way his older brothers stood up for him.

Marietta: In these pages here, turn to the core content that we tried to portray. We talked about how racial injustice still does exist today in our world, in our country. And how angry it can make individuals about shooting and police bias and the distrust and anger that often does develop within some African-American families because of this. And it's also the pride in racial identity that is prevalent, I think that's being stressed within this family. And we also used a pure teasing, Josh and his glasses as an example of bias. And what's really important is that individual and collective action can bring about social change! That was the message that we we're really trying to get across.

Scene 4: Emma and Josh Get the Opportunity to Respond to Discrimination They See at School

Dr. Ann Hazzard

Ann: The final portion of the book has Emma and Josh returning to the classroom.

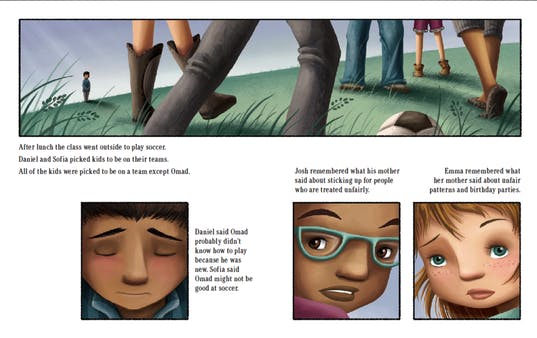

"The next day a new kid joined Emma and Josh's class. His name was Omad and he was from a country far away. Omad didn't know where to sit or what to do because it was his first day in school. He talked a little bit but it was hard to understand him. He said he was learning English."

Ann: "After lunch the class went outside to play soccer. Danielle and Sophia picked kids to be on their teams. All of the kids were picked to be on a team except Omad. Danielle said Omad probably didn't know how to play because he was new. Sophia said Omad might not be good at soccer.

"Josh remembered what his mother said about sticking up for people who are treated unfairly. Emma remembered what her mother said about unfair patterns and birthday parties ..."

We're not showing the final few pages to avoid a complete spoiler, but the core content in this final section is expanding beyond white and African-American to introduce immigrants. We made Omad an immigrant of unclear ethnicity on purpose but noting that other kids can be targets of prejudice and discrimination. We gave another example of bias in peer interaction. Emma and Josh are assertive in standing up for inclusion. And so we try to end the book with a feeling of empowerment that the children are able to start better patterns in their own lives.

Ann: So that's the children's story. We've tried to give you a flavor of it by reading a few pages. Hopefully it wasn't too confusing because obviously we skipped some pages.

But there is also a pretty extensive section in the book that gives parents information because we felt like parents might need some support in getting ready to read the book and being prepared for children's questions. So the parent information that's included in the book itself would give a rationale and some general tips for discussing racial injustice. We cover some unique issues that African-American parents may face. We give some sample vocabulary definitions. So we worked hard to come up with a child friendly definition of words like "prejudice," "discrimination." Those words aren't used in the book but we figured they may come up in follow up discussions. We have some sample dialogues of tough questions children might say.

And then in addition to that there are some further online resources that are actually available for free to anybody at the Imagination Press Website. There's a little tab next to the book that gives resources that parents can print out. It includes some book lists of other books on related topics as well as some additional places parents can go for help, including EmbraceRace, of course. We also have some resources including a very specific discussion guide for this book with some sample questions that educators could ask as they're reading the book to children. Parents could ask the same questions. So that's an overview of our book and we'll wait for some questions.

Community Q&A

EmbraceRace: Thank you so much. It's an awesome book. We won't even play coy and pretend that we don't think it's fabulous. The illustrations are amazing. The story is amazing. As you were saying before we came on and as was noted in the chat by some of the folks who are watching and listening, it's a really rich book. There are so many points of departure for different conversations with young kids in this book.

Let me start with a question. We know that you've all been going out and talking to a range of audiences. Marietta, let me start with you. You were saying that you have especially engaged African-American audiences, others as well, but certainly African-American audiences and I wonder if you could just give us a taste of the feedback you're getting?

Marietta: Sure. I've been fortunate enough to be able to go out and read our book in different settings with African-American kids and it's been positively received. I've read it in urban schools. I read it in a church setting where kids were as young as, I would say probably about age 6 and up to about 10 or so, with teenagers listening in the back. Kids, when you read the book to them, prefer to be really interactive, asking questions, pointing at the illustrations that are in the book and just really relating to it. I have a couple of mentees that are probably second graders, and they really loved the book. Generally speaking, the subject of race is something that is talked about fairly early on in the lives of many African-American families. So this book has really gotten a very positive response with people saying that it's very bold and much needed.

EmbraceRace: Ann and Marianne, you are speaking to audiences as well, more likely to be white audiences, mixed race audiences. What are you hearing

Ann: In general the children also respond very similarly. They're engaged in the discussion and they get the message of the book- that it's not fair to treat people differently due to the color of their skin or their race. And they feel empowered that they can make a difference and they can help people treat, and they can treat people fairly.

I think the challenge is sometimes with white parents and white institutions. We've had a mixture of responses obviously since we've read the book in a variety of settings. Some individuals and settings have been welcoming and very positive. Others have been a little cautious. I think that perhaps not seeing this as a priority area or worried about stirring up controversy. I've actually heard from both white and black parents sometimes some parents have worries about wanting their children to stay “innocent,” really is the words I've heard. So I think some folks that are doing more of a colorblind or color muted parenting approach are initially not sure they want to go there, where our book goes.

Marianne: I would add to that that some parents have said, white parents and black parents, have said that they're grateful for not just the story but the content in the back for ways to approach this difficult nuanced subject with their children. They've wanted to discuss this but they haven't really been sure how to do it. So I've heard that. And I've also had some questions from some parents who wonder about the right age to introduce this content. Is 4 too young? Is 10 too old? That has come up as well

EmbraceRace: Many folks have written in with similar concerns, those that you're already speaking about, Marianne and Ann. Besides parents, we've gotten so many questions from teachers at the Pre-K level, older, elementary school wanting to use this book or wanting to have that conversation and feeling and being anxious about their colleagues, about administrators’ reactions. Do you have any anecdotes about how people are using the book and what they’re doing when colleagues are reluctant or even not super progressive on race

Marianne: Yes I'll start with this one. In part, we're just starting that journey because the book came out in May. It was supposed to be released in June but the publication date was pushed up to be May 1st after Stephon Clark's tragic death. So we didn't get a chance to read it to too many schools in May - schools in Atlanta end before Memorial Day. That's just now starting up again.

I can say that if a school has an explicit anti-bias curriculum, if that's part of their curriculum, they have been more receptive to having us come in and they're not just interested in having us read the book. They want a workshop for the teachers. They want to have total buy in and they want help to develop a plan that's suitable for their specific needs and specific grades. Sometimes they say come in and read it. They don't have a plan after that.

Ann: We've had two schools like that. I think the age question is an important question and we have after we've read it with kids of ages from 4 to all the way up to 10 and had discussions with preschool educators, I think we're all generally on the same page that probably for most settings and most kids it makes sense to read it to 4 to 5 year olds in a family situation or a very small group situation. That's because of attention span issues and just in a large group I think there's more opportunity for misunderstandings or questions, kids have questions or confusion that doesn't get addressed. But it's been very successful to read it to 6 to 9 year olds and obviously you have a somewhat more sophisticated discussion with the older kids. But it's gone fine with with all the kids in groups of those ages.

Marietta: I'd also like to comment on reading our book in a school system. What's happening now is I've approached one of the larger private schools here in Atlanta and the racial composition is pretty diverse but more African-American now then it was in the past. And what they've asked me to do is to wait and let them meet with their parent advisory board to get buy in and then have us come in and talk with teachers. So it really does vary but reception so far has not been surprising or particularly negative.

EmbraceRace: One thing that's wonderful about the book of course is that there's a lot of modeling for adults. We all wish we were those parents who respond so well! And the portrayal of the older siblings are also spot on. But there were a couple places that that gave me pause, two places in particular. So one is when Emma's family is talking about really white peoples, the complicity of white people in slavery and in other historical wrongs, and the little girl responds.

"Did our family do those bad things a long time ago?" asked Emma.

"Yes," answered her mother. "Back then many white people thought they were better than black people even though it wasn't true."

This! We know there are lots of reasons why many white people want to hedge against any responsibility for things that happened in the past. Of course you talk about the present, too, which is hugely important. That's the next line. But staying with the taking responsibility for historical wrongs for a moment, most people of any stripe, certainly whites in this country, don't want to acknowledge that to, much less embrace that with their children. I wondered if that's come up and if you have anything to say now, perhaps to those of white parents who might be listening and wondering, "Could I really acknowledge that to my children?"

The other thing I want to say very quickly is at the end - you said you didn't want to give a spoiler. But I think it's fair to say that the children in the story step up. In our experience, we've found that you young children like our kids who are 7 and 10, as well as younger children, in some ways have an easier time right standing up for fairness even with their peers. But as they go on it will become more difficult, not just to be kind themselves but to be proactive, agents for justice especially when it means confronting peers and friends. So I just wonder if you could say a little bit about each of those. Can we start with the white parents acknowledging?

Marianne: Thank you for pointing out that text. As you are talking about it, I'm thinking of another way we could have made it even better. Basically Emma says, "Did our family do those things a long time ago?" And mother said, "Yes." What I think would be even better that we did not put in the book was, "Yes, and our family continues to do things." Right?

Marietta: That's great, Marianne.

Marianne: I mean so many white people say, "Oh well, you know, my family, we were immigrants. I wasn't here when all those terrible things happened." Or come up with some other excuse. Or someway of making it less relevant to their children's lives or to their lives. So we wanted to take a very different approach which was, "Yes. Our family did do this a long time ago."

Ann: But I think your question was has that created resistance in white families. I don't know the answer because, and maybe y'all have had an experience with a particular. Often when we are trying to engage institutions or families in reading the book, they haven't read it yet. So I don't know if that line is preventing them from reading it. No one has directly had a negative reaction to that with me but they may not have not spoken up.

Marianne: I've had two.

Ann: You have?

Marianne: I've had one person in my family. This family member said, "Well there's white slavery, too, Marianne." And then I had some after our newspaper article came out in our local newspaper here in Atlanta, someone called in and confronted me about the part about police officers making mistakes. So there has been a little bit of negative pushback.

EmbraceRace: Let me say a quick thing about that because, I think, certainly yes, people will say, "we weren't even in this country. My people came to this country in the 20th century," and those sort of things you've said. But I think a big part of it, too, is really that families typically don't pass on those stories. You will hear about the people who did wonderful things back in the day and embrace those, lift those up. Great granddad was ... whoever. Our family stories are sort of like Facebook!

Marianne: They're curated.

EmbraceRace: As history is curated, right. So it makes it then a lot easier for people to not acknowledge it because they honestly may not know. And everyone wants to think that they were on the side of the angels. Marietta, I wonder if you can speak to that but I'm also wondering about the end where the children stand up. You know even though it means telling their peers to step off. And has anyone spoken to that? What do you think about the challenge that, say, a 12-year-old child is probably going to have standing up for Omad in this case?

Marietta: I'd love to speak about that. You know I guess I have two responses. First, I've had children who I've read the book to who really relate to that situation. They can connect to the fact that it's not right to treat people unfairly, based upon the fact that they're a girl or they're a boy or that they look different - that that is not right. And so they really gravitate towards that. That's a concept, you should be nice to people. It's not right to be unfair.

In terms of what you were saying about recognizing the not so positive parts of our history. It was really important to us that this book served as an example of how to engage families in difficult conversations. It may be that, even with young kids, they don't get "the big picture." But the fact that the conversation is started leaves the door open for future difficult conversations. That's what was really important to us. We knew that just writing one story wasn't going to solve the problem. But we thought that it would be really important to model how to have these conversations and to leave the door open for future ones.

EmbraceRace: We're getting a lot of questions about police and about how you all would advise people to talk to kids about police. The police could harm or kill you, right, especially if you're in a targeted group. How do you think about talking to young kids about approaching police?

Ann: This is another reservation that some families have expressed of wanting their children overall to still see the police as helpful. Or not wanting kids to be worried about whether police officer A is a bad person or a good person.

We did try to present a balanced view of police, that they're not all bad or all good, while remaining true to the fact that most African-American families view police officers with a great deal of suspicion and anger for very understandable reasons. But I think in our experience what most kids have come away with is an understanding that police officers can make mistakes and that sometimes those mistakes may be racially motivated.

I did ask couple of groups of kids follow up questions after we've read the story. Questions like, what what are police for? What do the police do? What are some of their duties? Do you know any police officers? Have any police officers ever helped you? One was in a school settings where they had a police officer at the school. Most of the kids, this is a primarily African-American school, they had pretty positive views of their school police officer even though he was the person who they got sent to sit next to when they were misbehaving. I think if you ask those kinds of questions kids emerge with what I want them to emerge with: police have some helpful roles but some make mistakes. That's the view they end up with and I think that's an okay view.

Marianne: You know it's a hard conversation to have and it's uncomfortable for us. But development is a little bit on our side because while young kids tend to be more rigid in their thinking, as they get older their beliefs get more nuanced and more articulated and integrated. And we discuss other things with our kids that are uncomfortable. We teach them who's allowed to touch their private parts and who isn't. And we do that because we believe that our temporary discomfort is outweighed by the need to keep them safe. Personal safety is really important so we discuss that with our kids even as young as 5 and 6. We also believe that the outcome of racial justice is important enough to have discussions that might make us a little uncomfortable.

EmbraceRace: Thank you for that. You mentioned earlier, Marietta I think when you were describing the book about wanting to expand it beyond black and white. So you have Omad and you've talked about how he's of an indeterminate of race, ethnicity, nationality and so on. And you did that very deliberately.

One angle on that which I really loved is you're interest not only in promoting inclusive racial sensibilities among kids. But also having them be proactive in their racial justice work, which I love. And I love the fact that you have here you have Josh and Emma, a black child and a white child who are both taking the responsibility of reaching out to a child of color. Josh in particular is not simply a victim who needs to be resilient. He is also an agent of social justice and change. You talk about how together they can help change the pattern of interaction in their school. I think that's phenomenal.

I'm just wondering what's your general thinking about the way that this book promotes, understands that there are meaningful dynamics among children of color, and among adults of color as well. Have you gotten any response to that? It's not just a black/white thing or a white/non-white thing.

Marietta: I would say that the responses have been varied. Kids have really liked the fact that there's a black kid, there's a white kid, and there's somebody who's not black or white and how important it is that we all play together and that we all be nice to each other, which is what they like to say time and time again. What was important to us in writing the book is that it really reflects the importance of being fair and being involved in social justice and not discriminating, but also that it can be relevant to other kinds of "isms." You know be it sexism, discrimination against people who are LGBT, because of socio-economic status. But we really thought this could be a platform to have discussions which not only are related to race but are much more in context as well.

EmbraceRace: Marianne or Ann, did you want to come in on this point?

Marianne: I think we wanted to give kids specific concrete suggestions for things they can do in their own lives right to step up and to fight racial injustice when it occurs. And I was listening to you before when you said it's not so hard when you're 5 and 6 but it's so much harder when you're you know 13 or when you're 20 and you're standing up to your boss. So it's in some ways easier for little kids to do it than it is for older people to do it. But we wanted them to have something to do. We didn't want the lesson to be "don't do this." We wanted the lesson to be "do this" and you're going to reap the rewards. So it was very important to have both kids join together and helping Omad at the end.

EmbraceRace: Thank you for that. We have some questions that came in early about your partnership and really someone basically asking before reading the book, is anyone a person of color among the writers. There is. [Ann and Marianne identify as white and Marietta identifies as African American.] My question is how you all came together to write this book and also whether you get questions about that when you present separately. There is such a need and a lack of kind of #OwnVoices stories right #OwnVoices (twitter.com/hashtag/OwnVoices) that I wonder how you're differently received and whether you get questions about that?

Ann: We all worked at Emory School of Medicine together for over two decades. Marietta is now at Morehouse. But we got to know each other well as colleagues and as friends during that period. We were working with a primarily African-American population which helped Marianne and I become more fluent in the issues that were important to those families. I think that knowing each other that long and having a shared commitment to underserved populations was the glue that brought us together and enabled us to talk openly as we were writing some passages and deciding what to say. And I think that helped. The book couldn't have been what it was without an interracial collaboration. Certainly when I present alone I make sure from the get go to acknowledge my coauthors and to talk about how we know each other and that we are an interracial team. Because it would be presumptuous of me to try to write a book that in part was targeted towards African-American families without that collaboration.

Marietta: Sure. I agree 100%. What we've tried to do when it's possible is for all three of us to be together and it really, when all three of us are together people commented on how wonderful it is to see us talking openly about these difficult subjects across races. When it's not possible for all three of us to be together, especially presenting to African-American groups of people, I think it's really important for me to be present with one of my coauthors. Again so that people can understand the perspective from which it came. It was really a multiracial effort.

EmbraceRace: Thank you for that. We're getting a number of questions about pushback and the context in which that pushback comes from for a lot of people is with their own people, it's not with the kids. It might be with a partner. It might be with certain extended family or friends. It might be with a teacher or if you're a teacher it might be with some of your students' parents.

We touched on children standing up with their peers but sometimes we're the ones who might be mustering the courage to stand up with our peers. And I wonder if you could offer any wisdom to those of us listening for how you might do that.

And let me add one little bit of detail. You know there's a lot going on in the book. Clearly there's a message of inclusiveness and of nurturing resilience in kids of color, which are two of our goals with EmbraceRace. I think a large number of people could embrace those goals. Not everyone. But my guess is that fewer people embrace the message of proactively fighting for racial justice. That means putting yourself out on a limb a little bit more. So how do you stand up with people who might accept some of the message, "I would go this far" but aren't going to accept the whole message?

Marianne: So this is where courage is needed and sometimes patience with yourself and I'll give an example that doesn't come from the book but it comes from my teaching activities at Emory.

So I lead this cultural competence 4-session sequence and I have the students introduce themselves culturally at the beginning. But I typically have a white person who introduces him or herself by saying they grew up in the suburbs and they've led a sheltered life and so on and so forth and other people may say I grew up in that city. So this has happened for years.

And then sometime during the time we wrote the book, I had a woman say she was sheltered when she was young. And so I thought about it and I said, "Something bothers me about that word." So I got up and I wrote the word "sheltered" on the white board. And when she was done I said, "What if instead of this word, we used this word?" And I wrote the word "deprived." And she just kind of looked, she gave me this deer in the headlights look. And then I just said to her, "You know I think I've used that word, too, and I didn't realize until a few years ago what I was communicating with that word." And so now I don't use that word anymore. There are opportunities that come, that probably have come 15, 20, 100 times down the pike that I've let go. And I just don't let them go anymore.

Ann: I think with respect to our book specifically, we're in the early stages with this but, as we're negotiating with institutions ... Part of what you learn to do as a psychologist is meet someone where they are, so we're trying to find ways to meet institutions where they are.

That might mean proposing before they read our book proposing that they read some books that celebrate diversity but don't get into racial injustice as much. Or anti bullying books or books that promote empathy. Another direction is maybe negotiating to introduce our book later, to a later age group than we think is required. So maybe we do these softer diversity celebration books in grades 1 and 2 and get to our book in grades 3. That's a more prolonged timeline than then we would ideally set out. But if that's what it takes to make an institution comfortable then that may be a way to go. Because I mean the other thing we're aware of is we obviously don't want to encourage an institution to do something that they are uncomfortable with and their teachers are uncomfortable with. So teacher training and parent workshops and all those preparatory things may be another important part of what we need to do.

EmbraceRace: Thank you for that answer. There's a great question here about the book and the pictures that you showed that involves playing chess. What is additional layer of meaning of the chess pieces? When Josh, the young African-American boy, is talking to his family about the police shooting, his father and his older brother are playing chess and sometimes angrily because they are having this conversation about racial injustice and demonstrating anger and frustration. So I wonder what the significance of those chess pieces was for you all?

Marietta: That's a very interesting question. The chess pieces were really proposed by the illustrator, Jennifer Zivoin. We didn't propose them and we certainly had lots of discussion as to whether or not it playing chess is "typical" in many African-American communities and what did it in fact suggest. And after many discussions we ended up really liking the chess pieces. Because they're black and white. And it really allows the dad to show some emotion. So it was really our illustrator who came up with the idea. And we discussed it back and forth as we did with most things and ended up really liking how it portrayed that family's interaction.

EmbraceRace: Mhm. Don't all black men play chess? Andrew and I met in Chicago and all black men play chess in Chicago, including him. Really, by the lake there are a million chess games!

In the book, the chess game becomes a place to express frustrations at obstacles but as the conversation progresses, Josh starts to see a way forward, seeing what he can do. So the chess board comes to represent that strategy piece that his family supports him in developing, too.

Ann: And he's holding up a black chess piece as he talks about his own personal power. So I think it ended up being a visual metaphor that worked.

EmbraceRace: Right. In the chat, there's a wonderful sort of observation and question from Christiana. So let me read part of it. She says, "This is an important book. One thing that gave me pause, however, was the introduction of slavery and the concrete associations of Africa with slavery without any positive counterbalance in terms of where African people who were enslaved by Europeans came from. How do you think the presentation of Africa in reference to slaves rather than the enslavement of African people will contribute to children's understanding of Africa and Africans?"

I'll add what I think is a complementary point or really maybe underlining the same point which is this. I do think that the text of conversations in classrooms about slavery - where they happen - is, "Well, of course, that was a terrible thing." A dark episode in our history and so on.

We also hear from African-American students sometimes that this part of any American history course is what they dread most. Not all, certainly. And of course it can be done better than worse. But I do think we really teach our children and each other [however unintentionally] that it's better to be the one who enslaves than to be enslaved, that the worst thing to be is the enslaved. And if there are really good empowering ways to talk to African Americans and to talk somehow conscientiously to whites and others about slavery, it's certainly not widespread. I'm underlining Christiana's point that there are certainly some pitfalls perhaps to talking about slavery or to not talking about it well? Her suggestion is a counterbalance to slavery. To talk about resistance of the enslaved people and to talk about what African-Americans were able to do in spite of the phenomenal hardship of slavery, etcetera. She's asking for more context and a richer, fuller story. And she's wondering if there are pitfalls to not offering that.

Marianne: Yeah. I love this point. And thank you so much for sharing it. I think there's a couple things I take from it. First of all I totally agree that the use of the term enslave which focuses on the reprehensible actions of the oppressors is better than using nouns to describe people from a continent. However we doubted, I doubt that 4 to 5 year olds know the word enslaved. So we had to make a concession to development there. I get and agree with the point. The other point, that Africa comes up only when we're talking about slavery. I would hate for this book to be the only book that anyone reads about Africa or people from Africa. In Africa there's so many different cultures and there's just so much more than the fact that they've figured in our history of slavery right in the United States. So there's a couple thoughts I have about that. One is we should probably, when we update our additional resources because those will be updated every few months, is that we might want to add some text there and talk about that potential pitfall in the book and here are some other books to read that address Africa in a more comprehensive way.Marietta, you probably have some ideas too.

Marietta: Well I certainly appreciate your comments. Just given the limitations of how much space we had and the age that we were targeting, we weren't really able to address it as fully as we possibly could have. But I do think that we tried to make a connection by talking about really strong black leaders. There's Harriet Tubman, Nelson Mandela and there's a little picture of the Civil Rights Movement with the signs from marches. So we did try to make that connection but I think that was a great question.

EmbraceRace: We've referred to the illustrations which again are wonderful and they are such an integral part of the story. You'll miss a lot right if you're not engaging the pictures and talking about the photos and what they add to the story with the child.

We have a question about today, bringing it back today. Have you had children make connections once you've read them the book to current events, such as Colin Kaepernick and taking the knee at NFL games?

Marietta: The thing that comes to mind for me is the trip that Anne and I took out to Sacramento right after the shooting of Stephon Clark. We met with his little sister, his mom, family members and some of the sister's friends as well, older kids. One girl talked about the fact that since that shooting she's really afraid when her stepfather goes to work. Their car is broken. Now he has to take public transportation. And suppose he puts his hand in his pocket to pick up his cellphone, to call her mom to let her know that he's on the way [and he's approached by police]. She told us she's having a really hard time sleeping. But hearing this story we wrote really allowed her to begin talking about this. So certainly, I think that the book has served that purpose to begin to open up conversations which are difficult for people to have in some settings, sometimes in families and outside of families. You know so we're really pleased that it's been able to stimulate conversations for social justice.

EmbraceRace: Thank you. Thank you. Our time is at an end. We told you it would move quickly. We really appreciate the book and the conversation.

Marietta: We really enjoyed it.

Marianne: We appreciate it.

Ann: Bye!

EmbraceRace: Bye everybody!

Resources

“Something Happened in Our Town”: A Child’s Story about Racial Injustice – More about this book including free resources.

Children are not colorblind. How children learn race.

By Erin Winkler, PhD

Stages in children’s development of racial/cultural identities and attitudes

By Louise Derman-Sparks

Educators and Race: A Conversation with Author Ijeoma Oluo on Tackling Systemic Racism in U.S. Education

By Kara Yorio

Your 5-year-old is already racially biased. Here's what you can do about it.

By Andrew Grant-Thomas for EmbraceRace

Teaching Tolerance helps teachers and schools educate children and youth to be active participants in a diverse democracy.

Teaching for Change provides teachers and parents with the tools to create schools where students learn to read, write and change the world.

Marianne Celano

Marietta Collins

Ann Hazzard