MLK Day and the Danger of A "Single Story"

By Madeleine Rogin

In her TED Talk, The Danger of a Single Story, Nigerian author Chimamanda Adichie describes what often happens when Westerners talk about Africa — we tell the story of poverty and extreme suffering. In doing so, we miss critical understandings of the place and people, and we step into the minefield of continuing stereotypes and age-old misconceptions. Adichie recommends that we, in the words of another Nigerian author, Chinua Achebe, commit to telling a “balance of stories.” She proposes that it is only through this balanced telling that we will begin to truly appreciate the complexity, humanity, and depth of the lived experience on the continent.

Teachers all over the country are preparing to talk about Dr. King with their students. How many of us are asking ourselves if we are about to fall into the trap of telling a "single story"?

We are coming up on the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr., and teachers all over the country, from preschool to 12th grade, are preparing to talk about Dr. King with their students. How many of us are asking ourselves if we are about to fall into the trap of telling a single story, that is, the story of Dr. King’s life, disconnected from the hundreds of thousands of people who influenced him, fought alongside him, and continue to fight for the shared dream to end oppression and realize justice? What kinds of misconceptions, stereotypes, and untruths arise out of the telling of this single story?

Too often, when we teach about Dr. King, we perpetuate the “Hero” myth, the myth that an individual can bring about huge, monumental, positive change, all alone. Why is this a dangerous myth to tell?

First, It Is Simply Not True

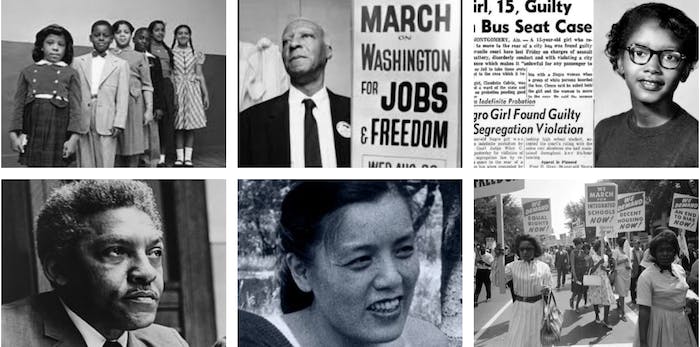

If it weren’t for people like A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, John Lewis, James Reeb, Thurgood Marshall, Rosa Parks, Stokely Carmichael, Claudette Colvin (to name a few) and groups such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the CORE (Congress Of Racial Equality), Dr. King would not have had the platform, the support, the mobilization, or the means to get his message across, let alone bring about the changes in the legal system that came out of the Civil Rights movement.

When we don’t tell the multiple stories that influence the movement, we erase so many people who contributed and fought for justice. And our students don’t appreciate that big changes come from many people working together, of varying races, ages, and backgrounds. Our students don’t gain an appreciation for the complexity, humanity, and depth of the story of the Civil Rights movement then and the continuation of racial and social justice movements today.

As a White Kindergarten Teacher, I Have Fallen Into This Trap Myself

Every January, I used to read to my students a couple of books about Dr. King, books that had powerful messages about non-violence as a strategy for change, about the evils of racism and the need to end it.

But I was never sure how to tell this story to my young students, and the experience of talking about racism was so uncomfortable for me, that, when a student would say something to which I didn’t know how to respond — such as wanting to know more about the assassination, or wanting to know which of the students in the room wouldn’t have been allowed to be in our classroom during segregation — I would cut our conversation short, stress that times have changed and we can all be together now, and move on to a subject that I felt more competent to handle.

As a result, my young students did not leave my classroom with a deep understanding of how to work against racism, or the strategies Dr. King used, or how the fight for social justice is ongoing, let alone with a deep understanding of what racism is. I was not proud of my teaching, and I felt an urgency to change it, especially because I am the mother of two biracial daughters (black/white) and I knew I owed it to them, as well as to my students, to figure this out.

I Spent Years Studying How to Do A Better Job.

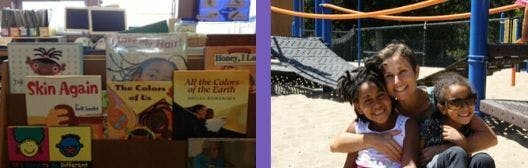

I read anti-bias educators, such as Louise Derman-Sparks, who suggests teaching about race and skin color before teaching about racism, so as to clear up any misconceptions and biases that can develop in young children.

I read white anti-racists such as Tim Wise, who illuminates the privilege around “choosing” to engage in conversations about race for whites, as opposed to the experience of race and racism for people of color, who are often not given the choice, but are constantly navigating and dealing with race and racism in our society. I read Shelly Tochluk’s Witnessing Whiteness, which breaks down the history of whiteness in America, and its ties to ideas around “goodness” and humanity, and its absolute subordination of blackness.

I read James Baldwin’s “The Cross of Redemption,” a collection of previously unpublished essays, which further helped me understand the difficulty I was having, as a white American, in talking about race because of the “invisibility” of whiteness — a racial identity that, at its core, is about skin color privilege and exclusionary practices.

I read Ta-Nehisi Coates, Bryan Stevenson, Howard Stevenson, and Michelle Alexander, who illuminate the racial disparities that exist today (in the prison system, health care, education, housing, etc.) and who stress the importance of changing the narrative around race in our country by telling the truth about how racism continues to influence so many aspects of our system.

Lastly, in that burst of learning, I read Taylor Branch’s extensive three-part series on America in the time of Dr. King, and learned about so many people and organizations that worked alongside King in his fight.

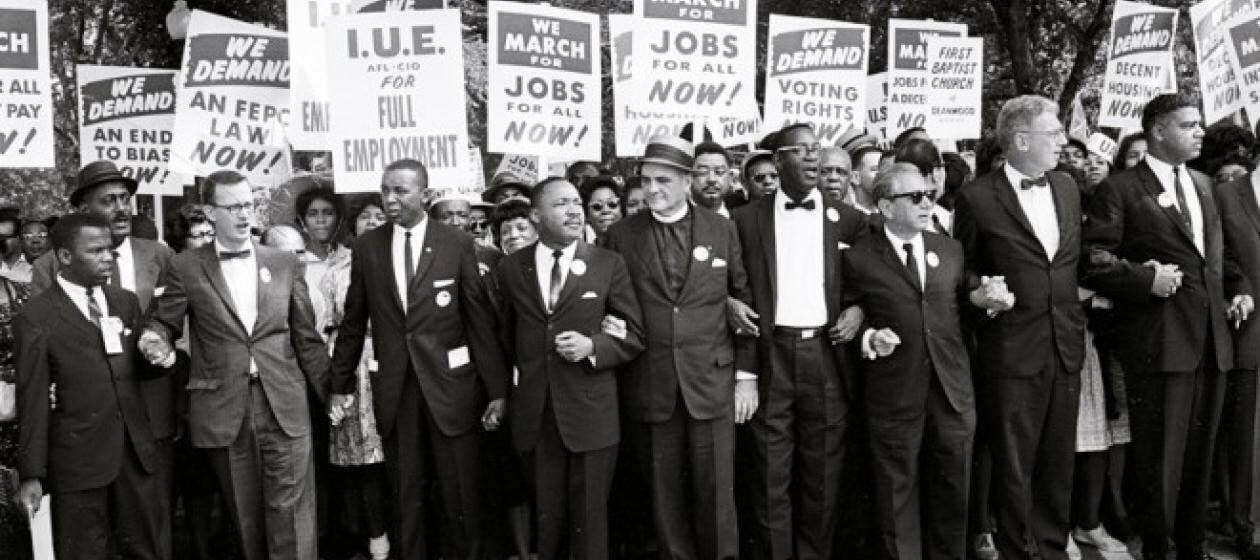

Dr. King with civil rights leaders during the March on Washington, August 28th, 1963.

When We Perpetuate the "Single Story" We Do Harm

I am not suggesting that every teacher in every school in America read the books I read before leading a discussion or preparing a lesson about Dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement. But I do think there should be required reading about white supremacy prior to teaching about racism and the Civil Rights Movement, especially for white teachers.

Let's face it, many white teachers engage in the topic of racial discrimination only once a year for MLK Day (if that) and our understanding of race and racism is often limited and immature. The invisibility of our own race as white people (white supremacy), and the prevailing idea that not talking about race is more egalitarian (being "colorblind") have limited our understanding and comfort talking about race.

But we have a choice. If what we want is for our students to gain a deep understanding of the themes of the movement, such as the importance of standing up against injustice, non-violence as a direct action for change, and the ongoing struggle for justice, then we owe it to our students to expose them to the Civil Rights Movement in all it’s complexity.

The stakes are high. If we continue to treat Dr. King as a single story, uninfluenced and unaffected by all the people who also fought — and fight — for change, we do more than limit our students’ understanding of the movement for justice of which Dr. King was a part. We do something much worse. We make it harder for our children to see and be “changemakers” themselves.

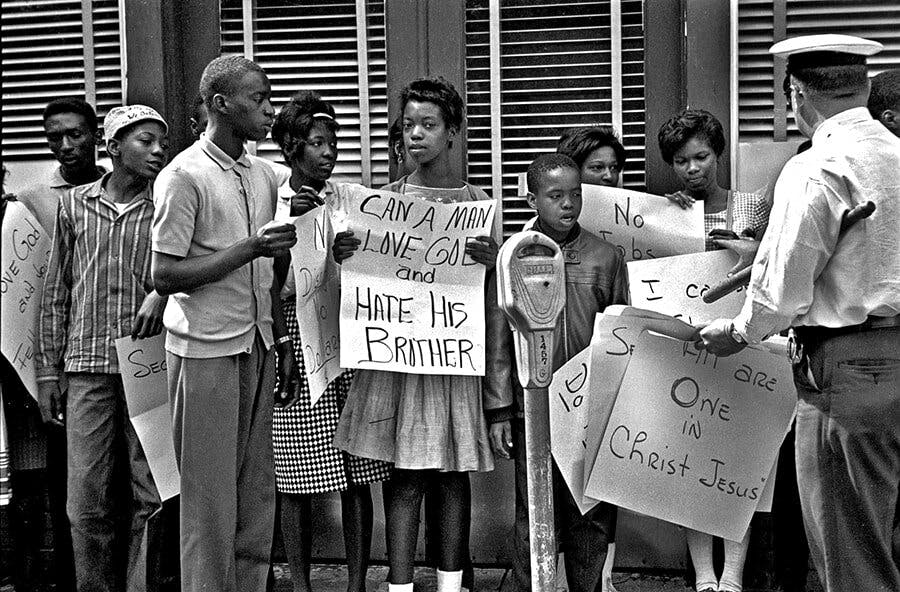

1963 Birmingham Children’s Crusade, a march for children protesting segregation of public spaces

Madeleine Rogin

Get Insights In your Inbox

Join the EmbraceRace community! You will receive the newsletter with our latest on race & kids, including upcoming events and opportunities, resources, community news and curated links.

Subscribe