"Lives in Limbo": What's next for 600,000 Dreamers?

Last week the US Supreme Court ruled that the Trump administration's plan to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program was "arbitrary and capricious," delivering a temporary victory to the more than 600,000 young people the program protects from deportation.

Watch this conversation about the experiences of the undocumented immigrants known as Dreamers before and since the enactment of DACA, about what it means to live and plan toward a future under conditions of extreme uncertainty, and about the road ahead. We are joined by special guests, DACA recipient Fernanda Oliveira Costa and Executive Director of Freedom University, Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis. A lightly edited transcript follows and resources follow that.

Melissa, EmbraceRace: Tonight's session, "Lives in Limbo": What's next for 600,000 DREAMers? It's one that we've we're excited to have. We were really taken aback by last week's decision and happy about it and want to know what to make of it. The court ruled that the Trump administration's plan to end DACA, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program was arbitrary and capricious. That was a victory for DACA recipients and for many of us who love DACA recipients.

What does it mean about the road ahead? It wasn't a clear signal that the court was in favor of DACA. It was more a, "you didn't go about this the right way", so we're wondering what this means for the DACA recipients, and also of course, for all DREAMers who are a bigger group than the DACA recipients. We're going to learn more about that today.

We have two really wonderful guests.

Fernanda Oliveira Costa

Andrew, EmbraceRace: The first I'll introduce is Fernanda Oliveira Costa, who is a DACA recipient, who came to the US from Brazil at age 15 with her mom and her three sisters to escape poverty, injustices, and the danger that girls and women face in Brazil. She has been in Massachusetts for 18 years now, and thanks to DACA, is on a journey to finish her college degree, thanks to the support of her communities, and then plans to pursue a Masters in Public Administration after that, sometime in the near future.

She's the Executive Assistant to the president and Project Coordinator for the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC), which by the way, is a fantastic organization that I had the pleasure of serving on the board of for seven years. We love them. This is how I met Fernanda, and I'm really glad to have done that. She supports a smooth and efficient operations of the ISC Board of Directors and the president of the leadership team. Again, I can tell you from personal experience that she does that, and does it really, really well. Fernanda great to see you. Thanks for coming.

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: Thank you for having me. It's an honor to be here.

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis

EmbraceRace: Then I want to introduce as well, Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis, who is a human rights educator originally from rural Minnesota, raised in a biracial household. Emiko now leads Freedom University in Atlanta, Georgia, which is a modern-day freedom school that offers rigorous college preparation classes, college and scholarship application assistance, and movement leadership training for undocumented students who have been banned. A lot of us don't know this, banned from equal access to public higher education in Georgia and elsewhere. As an activist, Emiko has engaged in numerous direct actions and been arrested four times in the Kingian tradition of nonviolent civil disobedience. Emiko, it's great to have you here. Thanks so much for coming.

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: Thank you for having me.

EmbraceRace: Emiko, let me start with you.

Can you give us a quick background on what DACA and on Dreamers, too, so we understand where the term came from?

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: Absolutely. In my work, working at the only sanctuary school for undocumented immigrants in the world, we present all across the country about our work, and oftentimes, undocumented students sharing their stories and presenting on the issue of undocumented youth access to higher education. Many people don't know the difference between DACA and The DREAM Act, and I'm happy to provide some context to that. Both are acronyms. DACA stands for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and it was a memorandum that was announced by the Obama administration on June 15th, 2012. That date is significant because it's actually the 30th anniversary of the US Supreme Court decision Plyler v. Doe, which for educators is a really important decision because it says that all young people, regardless of their immigration status, have the right to free K-12 education, recognizing that education is a human right, recognizing that we all benefit when young people are educated and have a safe place to learn.

In recognition and in honor of that 30th anniversary, DACA was announced. It's a memorandum. It is not legislation, and that's really important. It was announced, again, on June 15th, 2012. And that day, when you talk to undocumented young people who were here and experienced that, it was a moment of celebration and immense relief, because it does three really important things.

One, it provides something called prosecutorial discretion, which means that if you're before an immigration judge, that judge should use discretion and refrain from deportation, so prosecutorial discretion. Two, it provides a temporary social security number so that someone can gain a work permit and work with authorization. Three, it also provides eligibility for a driver's license. We joke that it means that you also have to know how to parallel park, which many of our students don't know how to do.

But a driver's license, more than allowing someone to drive and drive safely to work, and often drive their families safely, it's also an important source of government ID that allows many young people to do many different things beyond just driving. Going to movie theaters with friends, using it to go to a club if they want to etc. so, that ID was really, really important.

But what many people don't understand is that, DACA has very, very strict requirements. That is why there's a lot of undocumented young people, but not everyone qualifies.

For example, you have to have arrived before June 15th, 2007, and be able to prove that you have lived here continuously since then, and proving where you are at any given point for a long period of time is very difficult.

Two, you have to have arrived before your 16th birthday. You have to be in school or graduated from high school, have a GED, never have been convicted of a significant misdemeanor or have up to three minor misdemeanors and many, many specific requirements.

For example, I have many students, about 50% of my students have DACA and 50% don't. Those who don't often came right after their 16th birthday. I have a student who went home to visit a dying grand-parent and was not here continuously. There's all these different reasons. Each one, we have empathy for why someone doesn't qualify, and yet they are not able to get DACA.

DACA also costs $495 to apply for and reapply for every two years plus legal fees. While DACA does provide some source of relief, it's also very difficult to apply for it and a source of stress and financial stress for families.

DACA is different from The DREAM Act, which is an acronym for the Development Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act. The DREAM Act was first introduced in the US Congress on August 1st, 2001. I teach college level students now, and I have students now who were born after 2001. People have been literally waiting for the DREAM Act for their entire lives. I joke that if DREAM Act were a person, it'd be old enough to vote for itself today, that is how long the undocumented community has been waiting for the DREAM Act, and it is failed legislation, the 2019 Dream and Promise Act also failed. That is the difference between DACA and the DREAM Act. It's really important for the audience and the general public to understand this difference.

EmbraceRace: Thank you so much. I want to turn now to Fernanda and ask you, just hearing those specifics of the details. You're a Dreamer, and I'm wondering how DACA and the decision recently and the uncertainty before and how that has affected your life.

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: Okay. First, I came from Brazil to the United States with my mother and three sisters at the age of 15. This was shortly after concluding ninth grade. This was early 2002. When I came, I came with a visa which allowed us to stay legally in the US for up to six months. I remember during that time, my mother did everything in her power to apply for a more permanent solution for us to stay. But the way the system works, this just wasn't an easy process. It just was not possible to change our status. I remember, since I was 15 years old, lawyers saying that the only way for us to change our status would be if one of us would get married to an American citizen. With time, we became undocumented, and to stay in US unauthorized was a very, very difficult choice for my mom.

Eventually, with the increase of pressure, all of my family ended up moving back to Brazil. So since 2007, I am the only one here. I was about 20 years old. I decided to stay, not only because, as EmbraceRace mentioned earlier, I wanted to escape injustices and danger that girls and women face in Brazil, but also, I wanted to pursue higher education in America. As many call it, for many years, I've lived under the shadows and was unable to pursue a college degree, most work opportunities, or even visit my family in Brazil. That was not until after the DACA program, which came out in the summer of 2012. That's just to give some background information. Then second and more personal, in addition to adapting to a new country and having to learn a different culture and language, and having to learn to live in this limbo really, growing up in America as a teenager was initially a lot of fun.

I got to see snow for the first time. I've lived in Massachusetts for all of my time here. Finally, I got to build a snowmen, women, children, and pets, ride on these really cool yellow school buses, which we didn't have in Brazil. For once, not have to wear these ugly school uniforms we used to have. Most importantly, I felt safe in America. I felt safe from danger that I was exposed to since a very young age in Brazil. At the same time, my family and I also had access to foods that we couldn't always afford in Brazil, to be honest. I'm talking about simple things like cereal, peanut butter, and M&M's. My fondest memories of growing up in America are from high school. I will just never forget the love and support from my school teachers who went above and beyond to help me learn when I could barely speak English.

They were the only ones really, other than my family, who knew my story, my undocumented status, and could understand what I was going through. I felt like I could be my true self around them. I felt safest around them. I hoped this would be the case with new friends that I was making in school. But then if you think about it, at around 15 years old, not every American child or family had knowledge or skills necessary to engage well with the immigrant community. It became just extremely hard for me, especially as an extrovert, and with the language barrier, and later with the undocumented status, to be in that position. I often felt lonely or that I had to hide. I struggled with a lot of shame, and sometimes felt like a criminal because that's how I would hear people and leaders in America talk about immigrants who were undocumented.

By 16 years old, I knew well what it meant to live under the shadow and not be able to dream of a normal life, or pursuing higher education while all my friends were planning for college. During, and after high school, because I couldn't go to college, I worked mostly as a domestic worker. In the beginning, my young adulthood, my work was initially more focused on surviving in America as an undocumented than it was in pursuing a career, just because I didn't have proper documents to pursue the jobs that I would hope to have. It wasn't until DACA came out that I was able to pursue a college degree and work opportunities in my area of interest. Because there are very limited scholarships or even loans that DREAMers can apply for, it is taking me longer than usual to finish school.

It's been seven years now, but thanks to the support of my community, I have plans to graduate with a Bachelor's in psychology next spring. For the first five years of being a DACA recipient, I was feeling great. I was feeling hopeful. I've held on to the forgiveness granted to me and my community through the program. I could finally shake the shame off and do so many things that I could not do before. I even got to visit my family in Brazil once in all my years here, when my father had a critical health condition a few years ago. Then shortly after that, the new administration came in, and not as welcoming to DREAMers, and the program was rescinded early September, 2017. This was during the first week of the fall semester. This was ground shaking.

I heard the news. I remember, I was in my school's hallway when I was on my way to class. It was devastating. I remember having anxiety attacks, and as I looked around, it felt like my whole world was twisted. It was hard to even walk. That whole week I experienced anxiety attacks during class and thinking about this new level of uncertainty that my community and I had to deal with. This decision to end the program meant that me and my community would have to leave the country when our DACA documents expired. In my case, that would have been December of that same year, just a few months away. The DACA program didn't just happen. That's something that we should always keep in mind. For decades, leaders around the country have fought really hard, not just to establish a solution for DREAMers, but also to restore the program after it was rescinded.

Through a few courts battles, the program was partially restored in the last three years with the exception of first-time applications and the advanced parole, which allowed us to travel under certain conditions. Before the decision from the Supreme Court, I've had to live in this swing scenario of like, is a program going to end or will the program continue? It's just this back and forth. It felt like my whole life was pending on this decision. I didn't know if I could complete my degree or if I could adapt living in Brazil again after 18 years of living in America. The struggle with fear and shame came knocking again. Just one last thing I want to share is that, this is very personal, but also important for people to be aware of is, I've been in this journey since I was 15 years old.

Most DREAMers, even longer than I have, and at a much younger age, and my personal experience is that in each romantic relationship I've been in, there hasn't been a time in which the integrity of my intentions for dating someone that has a permanent status hasn't been questioned, by either the person I'm with, the family or friends. As much as I have loved America, it's great values, it's people and my life here, it has all come at a really, really high cost.

My personal experience is that in each romantic relationship I've been in, there hasn't been a time in which the integrity of my intentions for dating someone that has a permanent status hasn't been questioned, by either the person I'm with, the family or friends. As much as I have loved America, it's great values, it's people and my life here, it has all come at a really, really high cost.

Fernanda Oliveira Costa

EmbraceRace: Fernanda, thank you. That's a lot. Just to be clear, what you're saying at the end there is that, people you've dated or their families, and their friends are wondering about your motives in dating them, if you're dating a US citizen. It touches every part of your life.

Another thing I just want to underline, you were saying that under DACA, before it was taken away, and then some of it came back, you could travel to Brazil, but only under certain conditions. You couldn't even, all these years, you had to go when your dad was quite sick. It's a lot of years to not go for pleasure or to see people.

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: Correct.

EmbraceRace: So you came with your three sisters and your mom. They went back. When did you last see, other than the visit, when did you last see a family member here in this country?

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: That was August, 2007. That was about 13 years ago.

EmbraceRace: And you're saying that you've seen your family in person once since then?

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: Correct. For two weeks.

EmbraceRace: Right. That's a really long time, and you're young. Thank you, Fernanda.

Emiko, as you say, you wear the educator hat, and you've been doing that at least for quite a few years. The Supreme Court makes its move. You are clear in, what you said to begin with that DACA, I think, is a partial win. It's a win for now, but there's a much more. DACA is by no means everything, even if it were made permanent.

What does DACA mean for you as an educator in your work and the students that you see?

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: Sorry, my heart is still racing. Thank you, Fernanda, for sharing your story. Just remembering what September 5th, 2017 felt like just brought up a lot. It was a few days before we started our fall semester at Freedom U. It was really hard to welcome new students who always come in with their eyes wide open, not knowing what to expect in a room full of undocumented people for the first time. But to welcome them when they were in tears and uncertain of what this meant.

Speaking as an educator, Thursday, I have to be honest, I was not expecting a positive result. I think there's a reason why there's a saying that there's very few optimists in the immigrant rights community. It feels like you take one step forward and get knocked back two every single win. To be honest, we knew the Supreme court decision was going to happen sometime in June.

At Freedom U, we had two press releases ready. One that said Freedom University condemned Supreme Court decision. I hashed that one out, had all the quotes. Then there was another one that said, Supreme Court hadn't decided on a word blank, Supreme Court decisions had some bullet points. I think that reflects a lot about what we were expecting. While we were relieved that it was a ruling that what the Trump administration had done in repealing DACA in September, 2017 was wrong, it did not protect DACA per se. It was not the DREAM Act. It did not provide a pathway to citizenship. It basically said the Trump administration ended the program wrong, opening the door for them to do it right. It's not much of a relief. What Thursday felt like was one day to breathe and getting back to work the next day.

Thursday was just like this one long exhale. I'm like having to write that press release that I wasn't expecting to. But I do want to share that I'm speaking as an educator, but I'm also speaking as a citizen today, and recognizing the arbitrariness of that status. I happen to be born on one side of a border. That's literally why I'm a US citizen. My mom is a Japanese immigrant and a Green Card holder. Our lives aren't that different from undocumented people in terms of where we were born. We were all born somewhere and we are citizens in the United States, oftentimes because we were born here. I also am speaking as, probably the only educator in the country, if not the world, who only teaches undocumented students.

It's been the honor of my life learning from undocumented people every single day for the last, almost seven years. With that comes, I think a responsibility and speaking honestly and openly with my fellow citizens to share what I've learned from them. I want to emphasize that ... I know we're speaking to a lot of educators and that's why I'm really excited to be here today. Fernanda, listen to your story about just growing up, you said at first, it was fun. I hear that a lot from my students. K-Pop fans, people who love going to riding roller coasters, being normal kids. My students are incredibly diverse in their experiences and in terms of the countries where they're born. I would say three quarters are from Mexico, but we have students from central and South America, Afro-Caribbean students, students from Mali, Kenya, Nigeria, South Korea.

But what they share in common, is not only being from countries who were often colonized, looking historically, but they all share a story of stolen childhoods of, while having fun some days, always constantly having this cloud over their head of not knowing if they're going to see their parents when they get home. I think there's a burden in keeping secrets that could destroy your family constantly and not knowing who you can talk to. When there are counselors, everyone says, "Go talk to your counselor." They don't know if they can talk to them. They don't know who they can trust. I think Jose Antonio Vargas's book, Dear America, Notes of an Undocumented Citizen, talks a lot about all the lies that kids have to tell because of this system that we've created.

I think, as educators, we need to recognize that severe emotional harm that we are inflicting on young people because of our cruel immigration system, but combat that with educating ourselves and speaking about this openly and being clear about where we stand. I stand with all 11 million undocumented people, and I'm unapologetic in saying so. They are not others. They are our neighbors, and our students, and our teachers, and our friends, and our lovers, and our partners. They are not others. They are us. I think that once we know that and can claim that, we can have these really important conversations, but more importantly, be brave enough to fight alongside all of our undocumented friends.

I think, as educators, we need to recognize that severe emotional harm that we are inflicting on young people because of our cruel immigration system, but combat that with educating ourselves and speaking about this openly and being clear about where we stand. I stand with all 11 million undocumented people, and I'm unapologetic in saying so.

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: In short, Thursday was a breather, but as we said, DACA does provide prosecutorial discretion, a driver's license, work permit. But it does not protect the right to education, it does not provide a pathway to citizenship and it does not provide the right to vote, but we can tax them. We've created a system of taxation without representation, and everyone's okay with that. I'm not, and I hope that people listening recognize that the founding of this country on that same ideal, we're breaking it when it comes to 11 million undocumented people.

EmbraceRace: Emiko, we were talking about this a couple of days ago or yesterday about just that reality of DACA not giving people the right to vote, not giving a path to citizenship and comparing that to Jim Crow, and how racialized that is. Can you say more about that?

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: Sure. I'm speaking from Atlanta. I've lived in the South now for exactly half my life, for 18 years. I'm giving it away. I'm familiar with what it means to live in the South and to be in community with people of color and Black people. It's really important to recognize that it's racialized, because when we think of undocumented in the US imagination, we have a certain person in mind, and there is a reason for that. This "post-racial" society in fact criminalizes people of color, whether through the War on Drugs or through the criminalization of immigration. But we have criminalized people of color and then discriminated based on that criminal status.

What many people don't realize is that the US Civil Rights Movement and the Black Freedom movement, and the history of immigration intertwine and share experiences of oppression in many different, but similar ways. What I mean by that is, 1964, 1965, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, that same year, The Bracero Program was ended. That was a program in which the United States had 4 million contracts of farm workers from Mexico from 1942, it was a special wartime measure that ended in 1965. In 1965 was the first time migration and immigration from Latin America was criminalized. This is very, very recent history. We go back to 1924 in the Johnson-Reed Act when immigration was based on race. Immigration is a racialized system.

When we actually had quotas for immigrants from each continent, Europeans were welcomed based on proportions of people who were present in the 1890 census. People from Latin America, they did not have a cap because the United States wanted to keep the cheap supply of labor. African countries were limited to 100 people from Africa every year, and people from Asia were capped at 100 per country, except for Asians who were excluded because of the Asiatic Barred Zone Act of 1917. We have, deeply in this country's history, race and immigration are tied into our laws and that the modern creation of modern illegal immigration was 1965. That is important because when we're talking about civil rights victories and immigration, oftentimes when we look at powerful actors and interests, right as Black people were gaining freedoms and rights recognized in this country, the United States government was recreating a new exploitable labor force.

The migration patterns from Mexico hadn't changed over hundreds of years, but now is criminalized. That is important, because when we look at what DACA has done, it was an important program, but what it has done, looking at a historical perspective, it has created a population of young people of color, undocumented young people, and those who have DACA are overwhelmingly people of color. We have given them the right to drive to their low wage jobs, but be denied access to education and the right to vote. Some of the most important means of exercising power in this country. It is not a coincidence that the universities in Georgia that banned Black students in 1960 also ban undocumented students today.

[W]hen we think of undocumented in the US imagination, we have a certain person in mind, and there is a reason for that. This "post-racial" society in fact criminalizes people of color, whether through the War on Drugs or through the criminalization of immigration ... we have criminalized people of color and then discriminated based on that criminal status.

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis

Dr. Laura Emilo Soltis: The University of Georgia, Georgia Tech, Georgia College and State University, since 2010, undocumented students are barred from applying and being admitted to the universities, and it is illegal for undocumented students to sit next to their citizen peers. We need to recognize that it is not the Black Lives Matter movement against immigrant rights struggle. They are deeply interconnected. When we're fighting for racial justice, we're also fighting for immigrants. When we're fighting for low wage workers and a say in decisions that impact our lives, we're also talking about immigrant rights and affirming that Black lives matter. I think that this is a wonderful time in our nation's history. Even though it's painful, the veil is being lifted, and it's painful because people are now seeing in real time, the degree to which racism and xenophobia, and many types of hate, really do intersect and are ingrained in our laws.

The migration patterns from Mexico hadn't changed over hundreds of years, but now is criminalized ... We have given [DACA recipients] the right to drive to their low wage jobs, but be denied access to education and the right to vote. Some of the most important means of exercising power in this country. It is not a coincidence that the universities in Georgia that banned Black students in 1960 also ban undocumented students today.

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis

EmbraceRace: Fantastic information, Emiko. Really wonderful analysis. Fernanda, I want to come to you. I think at the beginning of this, you mentioned your mom, your sisters, your separation from them. I think you said that your mom might actually be watching, or certainly will be able to watch, which is amazing and lovely.

I wonder if you could say a word, of course, feel free not to, but I wonder if you'd say a word about what is the experience for her of watching her daughter, her third of four daughters, not just watching you here and now, hopefully, but all these years. It's a remarkable part of your story that you've been on your own here, physically, from your family. I'm sure they're aware of what's going on, the politics of it, of the path we have yet to go and the path you have yet to go.

I want to say, to be clear to folks, not only you're a DACA recipient, you've suggested this, you're an activist. I know you to be very much a social justice worker on a range of issues. You volunteer on any number of things. What do you think that's like for your family, for your mom?

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: They're very engaged. We talk regularly. They're very supportive. Of course, it's not ideal. It's not ideal that we don't get to see each other as often. I've been missing weddings. I've been missing birthdays and all my nieces and nephew being born. There is a lot that we are missing and just spending time together, but we continue to invest in our relationship. I know that they're proud and I know that they get to contribute to my life even though they're far. But at the same time, we've grieved together. It's very hard. It's very hard to see your family once in 13 years, especially when it comes around holiday seasons.

Easter, Christmas, I love those holidays, which I celebrate, but it's just really some of the most difficult times for me. But yeah, I just couldn't do it without their love and support. That's so tangible. That's the reason why I want to fight harder for the causes that I'm fighting for in America.

EmbraceRace: Say a bit more too about what comes next for you Fernanda, again, as an activist, as a DACA recipient, as a fighter for many things, as a full-time salaried employee, as a student. You have a lot going on. What comes next?

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: Yeah. I can mention three focuses on my advocacy efforts.

Considering that I have the privilege to be protected by DACA and to be in school, I plan to continue sharing resources that are available to the immigrant community, which a lot of times, they don't have access to these resources because they're not in school. These could include resources for mental health, financial or legal support.

Second, because I am learning to share my story more comfortably, which is really hard because it's so deeply connected to my whole life. I want to continue growing in that, developing that and to help American citizens in my communities to better understand in how to deal with the immigrant community. I say that, not in the sense as if we have to prove ourselves or justify ourselves, but to help bring things into perspective, to clarify simple questions like around the program, or what it means. Little things like that, and point people again, to resources where they can find more knowledge.

Thirdly, we need immigration reform that would allow for DREAMers and other immigrant communities who are not eligible for DACA but may have been here just as long, if not longer, that would allow for us to have a path toward a more permanent solution. Hopefully, to be out of this perpetual limbo someday, and in order to achieve this, my community and I will continue to call on Congress to pass the Dream and Promise Act.

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Fernanda. A big question that's come in from lots of people is, what can they do? What can we do to keep DACA recipients here, to get the DREAM Act passed? What can we do to widen our circle of concern, and to make you all feel safe here? Like you have the opportunities that should have. What do you usually tell people that they can do as advocates themselves, or maybe as new advocates?

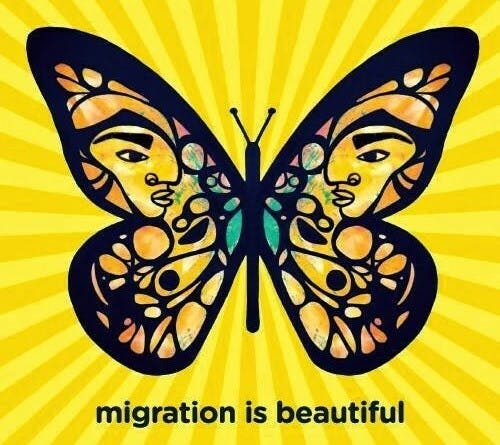

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: Fernanda, I hope I do this answer justice. I hear from my undocumented students daily. I hold myself accountable to them. I'll just try and share some things that I've heard from them that were not helpful going through the K-12 public school system and maybe some points of what we try and do at Freedom University to make sure students feel safe and affirmed. I would say to any educator, K-12 educator, that it's okay to feel overwhelmed by all of this information, especially if this might be new information, and that's okay. There's a lot of injustices in this world. We need you for the long haul, so breathe. Start educating yourself. But one of the most important things, and it might be different during COVID, but I do recommend that teachers put some sign, whether it's a butterfly or a poster or something that signals to undocumented students who might be "in the shadows" or not "out", to know that there is someone that they can talk to or trust. That's really important.

"Migration is beautiful" butterfly by artist Favianna Rodriguez

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: I would say, make sure that you have an open-door policy in case someone does want to open up to you, and you don't need to know all the answers, but the most important thing is that if an undocumented student does share with you, it's on their own terms. On their own terms is very important, and I think the US public is more versed in LGBTQ coming out stories. But in many ways, they're similar. The same tips apply of just not outing people, letting them tell you. If that's the case, it's not important that you know all the answers, but it's important that that student knows that you're there holding their hand and going to find the answer with them. Making sure the students don't feel alone. I think connecting undocumented students with undocumented leaders or community organizations is really important so they have community.

I would say to any educator, K-12 educator, that it's okay to feel overwhelmed by all of this information, especially if this might be new information, and that's okay. There's a lot of injustices in this world. We need you for the long haul, so breathe.

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: That is, sometimes, a difficult search if you might be in more rural communities, but most cities have strong undocumented organizations or immigrant rights organizations. Connect students with a sense of community of other undocumented people. Through that community, they will find safety and strength. Those are just some of the tips off the top of my head as an educator of what people can do.

But I think in terms of legislation, have your Senator on speed dial, period, for all reasons. But contact your senators' offices, your representatives. Make your voice heard in terms of the DREAM Act, if that is something that you believe in. We've been also learning, from these conversations on race and Black Lives Matter too, we need to be brave enough if we are not directly impacted, to be talking to our family members and our friends about this.

Oftentimes, we're more likely to hear better from people we know and trust. I think talking openly about DACA and the DREAM Act and what you've heard and learned from today, from Fernanda. If you want to also talk about the 10 million people who aren't covered by the DREAM Act and what it would mean to protect less than 10% of the population, where parents, moms and dads, and aunts, and uncles, and grandmas, and grandpas aren't covered. What does that mean? Maybe we should revisit the 1986 Amnesty by President Reagan, the Republican maverick that many current Republicans look to as an example. He passed a mass amnesty, and now amnesty is a no no word in this conversation. But what does it mean to have everyone in our society, regardless of where they're born, to participate in our democracy?

I think that's a good thing for people to have a say in decisions that impact their lives, for people not to be afraid of police or ICE. I have heard students who saw a domestic violence situation and didn't know if they should call police, because they didn't know if they would suffer the consequences. Everyone suffers when people are afraid of the police. Again, across movements, this is a common theme. I think many of the things that we're learning from many different movements that are going on does apply to this struggle for immigrant justice as well.

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Emiko. I'm thinking, so by my math, the oldest DACA recipients are in their late 30s now. We have a number of questions about the children of DACA recipients. Of course, as you have both said so well, we can go well beyond them. Who's a DACA recipient is a little bit arbitrary for a whole range of reasons, many of which you've touched on. Emiko, I'm thinking about the students that you have had who will be parents, no doubt, and many of their children, the vast majority, I imagine, are born in this country, they're US citizens. Birthright citizenship as they say. We know that that's been threatened. President Trump has threatened birthright citizenship. But it's not just their parents that they may be concerned about.

As you said, the aunts, the uncles, the grandparents, many, many, many people, a whole web of relationships. Again, Fernanda, your family members, your mom, your sisters. I'll start with you first, Fernanda, just what again, it's a very broad question. We have a whole bunch around the children, in particular, who are young. If the DACA recipients are in their late 30s at oldest, then you're talking about quite young children who are their children.

What would you like folks to know about the children of DACA recipients?

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: Yeah, just to add to what Emiko was saying, and considering that most of the audience here are educators and caregivers, I would invite people to consider prioritizing the health and wellbeing of our immigrant community. This I say by being a DACA beneficiary myself, and also as a psychology student, but it's really important to hold the value and importance of learning with us to deepen the sensibility, learning and transformation. As undocumented immigrants, we've had experiences that deeply impact our sense of safety, connection, or significance. The symptoms of these experiences include lack of trust, a sense of shame and guilt, need to protect, prove, or even dissociate. They have the tendency to last even after DACA, and possibly even after The Dream and Promise Act and permanent residency and 'citizenship come by.

As undocumented immigrants, we've had experiences that deeply impact our sense of safety, connection, or significance. The symptoms of these experiences include lack of trust, a sense of shame and guilt, need to protect, prove, or even dissociate... I would invite people to be sensitive of that, and also to cultivate resilience building, community integration by supporting our sense of wholeness, possibility, the ability to sustain pressures, and also to expand understanding in short and long-term impact of trauma in the mind, body, emotions and relationships.

Fernanda Oliveira Costa

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: I would invite people to be sensitive of that, and also to cultivate resilience building, community integration by supporting our sense of wholeness, possibility, the ability to sustain pressures, and also to expand understanding in short and long-term impact of trauma in the mind, body, emotions, and relationships, particularly if you're working with younger children, and help create a sense of safety and belonging. Because a lot of times, I remember my experience, where I felt the safest or where I felt like I belonged the most was in school. Because outside of that, I had to avoid being in a relationship with American friends, because I couldn't talk about my status, and also because of the language barrier.

But yeah, try to understand the sense of shame and rejection that can be interconnected with our backgrounds. But also, see us not as the problem in schools and work environments, or as the broken ones, but as treasures. I believe that, what we've been through, we are a part of what makes this country great. Our hard work, our endurance, our resilience for never giving up, our love despite of the oppression we've been through. Especially during this pandemic, as people are seeking shelter, safety, hand sanitizers or toilet paper, let that be a reminder that we're humans, just like everybody else, who desire safety, security, peace, and wellbeing.

Just as there are immeasurable amounts of love flowing towards me and my community, there are also constant accusatory and rejective messaging which we're exposed to on a daily basis, through television, social media, even people in our communities. We hear statements like deport these "illegal aliens" who are taking American jobs from American citizens. And this, while we're also helping create jobs for Americans. And just a clarification on this term, which I find very dehumanizing, there's no such a thing as an "illegal human." There are illegal actions. I would refrain from using that term and would ask people to reconsider if you ever hear this term, especially around children.

With that, I'll end with just asking everyone who's listening today to help us DREAMers and immigrants to transform this shame and pain into ongoing forgiveness and beauty. In fact, and this is something that gives me hope and that I hold onto is that forgiveness is something that has already been given to us through the DACA program in 2012. A shame really would be taking it away from us.

EmbraceRace: Yeah. Thank you for that, Fernanda. We're getting a lot of questions about resources. Emiko, you'd mentioned Dear America, the book Dear America by Jose Antonio Vargas, right? Are there other books? Maybe Fernanda you have some too that could help people sort of understand the situation of undocumented immigrants in this country who are early in their trajectory of learning and trying to explain to family members or friends.

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: At the moment, I don't have a recommendation for a book that's on immigration. But I have been reading White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo, which talks a lot about avoidance on these types of conversations and how to go about that.

EmbraceRace: Very connected.

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: I love it when people ask for book recommendations because I'm a teacher. Where should we start? This has less to do about immigration per se, but this is an essential book for teachers, Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire. Brazilian. Yay, Fernanda. This is one of my favorite books, and I come back to it every couple of years and always learn something. This is a little dorky and academic, but this is a history of immigration and labor called Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. That's a pretty deep historical book, but I teach these two books together. This is really important, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, which is essential reading for everyone.

Then Aviva Chomsky, who yes, is the daughter of Noam Chomsky, wrote this really great book called Undocumented: How Immigration Became Illegal. The introduction does a really good job of connecting Michelle Alexander's arguments of criminalization as the main way that racism is being justified and put into law to the undocumented community. I really recommend this book. We read this in my human rights class with Freedom U students. I really recommend this book because she tells stories in each chapter. It's not simply footnotes, which is fine and facts, but integrating facts into human stories. I really recommend Undocumented by Aviva Chomsky.

EmbraceRace: I love those recommendations. What is the butterfly symbol that you mentioned and it's meaning?

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: Sure. Yeah, so Fernanda, if you want to talk about it too, feel free to jump in, but I can maybe share a little bit about what it means to Freedom U. But specifically, the monarch butterfly has been used to represent the idea that migration is beautiful. It is also very painful, but it is a natural process that creatures in nature do it, humans do it. Specifically, the monarch butterfly, I think in Morelia, Mexico, crosses the US Mexico border freely as do many immigrants. I also want to note, this is a totally different footnote aside from butterflies. But I think I need to mention, if we're talking about racism, to recognize that the fastest growing undocumented population are actually Asian. More undocumented people may actually look like me than what people have in their minds.

They're coming by plane with visas. Again, no alligator moat or border wall can prevent that type of immigration. That was a side note. Coming back to butterflies. That's why the monarch butterfly is often used as a symbol for the undocumented immigrant community and undocumented youth movement. At Freedom U, in addition to our free classes and helping students apply to college and scholarships, we also do human rights learning and social justice leadership training. In terms of social justice leadership, we also do direct actions in the tradition of Kingian nonviolent civil disobedience.

The monarch butterfly has been used to represent the idea that migration is beautiful. It is also very painful, but it is a natural process that creatures in nature do it, humans do it.

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: We're in the heart of Atlanta. Many of our mentors are SNCC veterans from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or a part of the Atlanta Student Movement. And we have done sit-ins, and with DACA, it provided, remember that thing about three non-significant misdemeanors? It meant that that also opened up a door for advocacy. Many undocumented young people fighting for their DREAM Act were putting everything on the line, risking arrest and possible deportation and civil disobedience. DACA opened up a door for DACA recipients to participate in direct actions. On January 9th, 2015, on the 54th anniversary of the desegregation of UGA, the University of Georgia, undocumented students and their citizen allies from universities across Georgia sat in, in a classroom on the university of Georgia campus.

Five years had passed since it became illegal to study together. They had a class. The guest lecture was Lonnie King, who was the first chairman of the Atlanta Student Movement. What symbolized made that action powerful was that undocumented students were wearing handmade butterfly wings to symbolize that again, migration is natural, it symbolizes transformation, beauty and many of the qualities that Fernanda was talking about. And I think that's why it's become a powerful symbol of the undocumented youth movement.

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: Thank you, Emiko. You've said it really well. I would just add that it's, for me as a Dreamer, is a symbol of hope and joy whenever I see the butterfly in my professor's office or any office in the school. I really appreciate you supporting that in your school as well.

EmbraceRace: Fernanda, we only have two minutes. We're so appreciative of what you've shared here and your willingness to do that. As we go out, what last thing would you like to say to people?

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: You want to go first, Emiko?

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis: Yeah. I'm actually gonna read something, which is kind of a mantra we developed at Freedom U, getting ready for this decision. If undocumented young people are watching this, trying to get more information, or if you are a citizen or an educator and want to share this, it is on Freedom U's Instagram, which is our acronym, which is FU_Georgia. So, it's FU_Georgia is our Instagram name, so you can find it there too. But it's a reminder, it's kind of a mantra for our students.

"To undocumented young people who may feel scared and alone, remember this. One, a government does not define your humanity. Two, you have inalienable human rights, regardless of where you were born. Three, citizenship is about participating in the life of your community. It is not about papers. Four, no human being can ever be illegal, especially on stolen land. Five, the global movement for migrant justice will continue no matter what, and we need your voice."

That is what I'll end with. Fernanda, feel free to give some closing thoughts.

Fernanda Oliveira Costa: Thank you, Emiko. That was really beautiful. Thank you, Andrew and Melissa. It's still all so fresh to me, and I'm still processing it all. But what comes to mind, and I'll be brief on this is that the love and the hard work of all who have fought really hard has paid off, and this victory is ours. I can tangibly feel that love and justice have spoken louder than the hate and the lack of understanding that's around us. I am deeply grateful that America is keeping its promise to DREAMers, and I really hope that we're able to come forward with a more permanent solution. Keeping this program means that I and my community can plan our lives farther than the expiration of our DACA documents.

It means that we can continue to work legally, complete our college education, or even pursue graduate school. It means that we don't have to worry about saying goodbye to friends and communities that we've loved and who have loved us for several, several years, and it means that we also get to see our families again, in case there is an emergency, whenever the advanced parole is back. Most importantly, it means that people, now more than ever, dreamers (all who want to make the world a better place, not DREAMers exclusively) understand that DREAMers belong here. We are what makes America great. I'm just really grateful for all the support for this good news, and I have more hope for the future.

EmbraceRace: Thank you so much. Wow, for bringing the heart and the intelligence. We're so grateful to both of you. Both for what you shared today and for the work that you do in the world, and with community, and in community. Thank you. You're getting lots and lots and lots of love in the chat and the Q&A. A lot of fans. Teresa says, "Powerful and impactful. You belong." Amen. Thank you both. Thanks everyone, until next time. Bye-bye.

Resources (return to top)

Fernanda's recommendations

- COVID-19 Resources for Undocumented Immigrants/COVID-19 Recursos para Comunidades Indocumentadas – resources for undocumented immigrants, including state organizations

- Cosecha - Cosecha's Undocumented Worker Fund will redistribute your donation directly to immigrants impacted by the current crisis.

- Undocuhealth – United We Dream’s mental health resources for undocumented people

- Together We Dream - Financial assistance for all undocumented immigrants who have lost their jobs due to COVID-19

- Fernanda shares resources on Instagram @healingandrestorativejustice

Dr. Soltis's recommendations

- Top 10 ways to Support Undocumented Students – from ImmigrantsRising.org

- Dear America, Notes of an Undocumented Citizen by Jose Antonio Vargas

- The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander

- Undocumented: How Immigration Became Illegal by Aviva Chomsky

- Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire

- Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America by Mae M. Ngai

Also check out ...

- Freedom University in Atlanta, Georgia (led by our guest Dr. Soltis) is a modern-day freedom school that offers rigorous college preparation classes, college and scholarship application assistance, and movement leadership training for undocumented students who have been banned from equal access to public higher education in Georgia and elsewhere. Check out Freedom U's resources. Follow Freedom U on Instagram. Consider making a donation to FU here.

Fernanda Oliveira Costa

Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis