Let's Talk About Reparations: What Does the Publishing Industry Owe Our Kids?

By Zetta Elliott

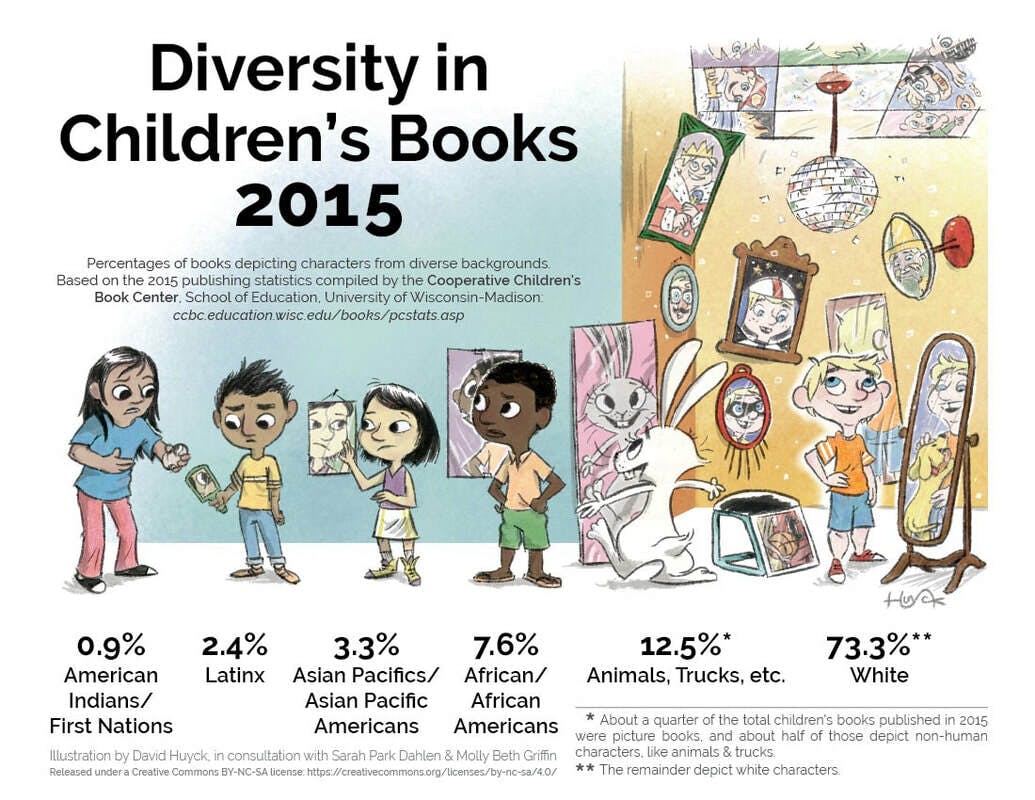

I was at St. Catherine University last month when Library and Information Science professor Sarah Park Dahlen unveiled this updated graphic on the state of children’s publishing in the US.

Dahlen, who teaches a course on social justice in children’s literature and gathered data for Lee & Low’s 2015 Diversity Baseline survey (DBS), had invited me to campus to make a case for community-based publishing. Illustrating statistics gathered annually by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, the new graphic makes it clear that we need alternatives to the traditional publishing model if children’s literature is ever going to be truly inclusive and accurately reflect the changing demographics of the US. (UPDATE: A graphic of the CCBC's 2017 publishing statistics is available at Lee & Low Books.)

The children’s publishing industry has predictably responded to the public outcry for greater diversity (#WeNeedDiverseBooks) by giving additional opportunities to cultural outsiders, spawning another hashtag movement to instead prioritize stories written by members of marginalized groups (#ownvoices).

Yet in her essay “On Autonomy: the Intersections of Ethnic Studies and Young Adult Literature,” Dahlen argues, “We need more than just opportunities to tell our own stories. We need radical change. We need an industry-wide understanding of the context in which our stories are told” (my emphasis).

In the talk I delivered at St. Kate’s that evening I contended that the publishing industry — like every other US cultural institution — operates in the context of White supremacy, empowering White children at the expense of kids of color and Native children.

The 2015 salary survey from Publishers Weekly confirms the findings of the DBS: publishing professionals are overwhelmingly White (89%). The writers and illustrators published — and paid — by the industry are also overwhelmingly White, and together they produce books that primarily depict White children.

In response to outrage voiced on social media (#OscarsSoWhite), the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences pledged to double its female and minority members by 2020. Could something comparable happen within the publishing industry?

Dahlen concludes her essay with a quote from a post on my blog in which I speculate on the efficacy of seeking reparations:

As the topic of reparations resurfaces here in the US, I can’t help but wonder what reparations would look like within the kid lit community. How could the dominant group ever make amends for the damage done to our children? For decades here in the US they have ignored our pleas for inclusion and perpetrated a form of symbolic annihilation by distorting or altogether erasing the image of Black youth. Can the publishing industry really be trusted to reform itself when those who uphold it haven’t acknowledged the harm they’ve caused?

Since writing that blog post in February, the topic of reparations has continued to make headlines in this country — most recently at Georgetown University.

It is a serious, sensitive issue that makes many people uncomfortable. Ta-Nehisi Coates made a strong case for reparations in his 2014 Atlantic article but for many, the word still brings to mind Dave Chappelle’s 2003 skit that spoofed the notion of African Americans finally “getting paid” for 400 years of oppression.

Obviously the publishing industry can’t simply write a check to make up for excluding and/or distorting kids of color and Native children for the past hundred years. But what if they offered vouchers to any parent interested in building a home library filled with “mirror books”?

What if publishers paid to build, staff, and stock libraries in the many public schools that have gone without for decades?

What if they diversified the publishing industry by adopting fellowship programs like the ones used effectively by HBO or Disney?

Or what if the Big 5 publishers promised to publish 25 debut authors from each underrepresented group every year for the next ten years — and gave them multi-book deals?

I don’t have all the answers, but I think it’s time we started this conversation.

I showed my video to some colleagues in the kid lit community, and asked them to share their insights on the topic of reparations and the children’s publishing industry.

Debbie Reese, scholar and founder of the American Indians in Children’s Literature (AICL) blog:

"As I consider the demographic I am most committed to in my work — Native children — and the idea of reparations, some key thoughts come to mind.

Right now in most of my writing and lectures, I speak about our identity as sovereign nations. I point to children’s books that, in some way, are grounded in our sovereignty. As most of us know, Native peoples are very badly represented — indeed, overrepresented in harmful ways — in children’s literature. And there are studies that show that those representations do harm to Native children’s self-efficacy.

What will help them? What can the White cis-gendered able-bodied women gatekeepers in publishing do?

One: stop publishing some of those books. They’re old, they’re outdated, they’re factually incorrect. As an industry, we move away from old books, naturally, all the time. We can do that with books like Island of the Blue Dolphins, too.

Two: start publishing books that depict us as peoples of nations, and begin that by publishing Native writers. Stop rejecting their manuscripts because they don’t look to you like the stuff the public will buy.

I offer those two suggestions with a huge caveat: I worry that people in power think that offering a form of reparation that is then accepted is viewed as, “There, I did it. I can cross that off my list.” That’s not reparation. That’s a superficial response that won’t maintain the kinds of literature and stories that Native and non-Native children need so that none of them are harmed by the books currently being published.”

Deborah Menkart, Executive Director of Teaching for Change:

“Major commercial publishers should make the next generation of children their ‘shareholders.’

They can provide a designated percentage of their profits to fund the publication and widespread dissemination of children’s books by people of color and Native Americans, with the selection of the authors, illustrators, and titles to be made by an independent group of scholars and activists in the field.

The outside selection is necessary because the institutions are currently staffed to maintain the status quo. This would not be “compensation.” Instead the children’s books would help to fight the historic invisibility that has made the demand for reparations so incomprehensible to most white people.”

Neesha Meminger, YA author and educator:

“Publishers and agents need to ‘put their money where their mouth is’ and offer solid, financial and/or resource assistance and allocation for work produced by and about PoC.

Some examples could be grants for authors of color, or setting aside a percentage of acquisitions each quarter that MUST be by AND about PoC.

I know that some people will complain that this sounds too much like Affirmative Action, but honestly…parity and equity are things that no one wants to do unless mandated to do so.”

Maya Gonzalez, author/illustrator and co-founder of Reflection Press and School of the Free Mind:

“At the very minimum, reparations should look like equity.

If in 2015 POC and indigenous creators stood in equity with white American children’s book authors/artists, we would have published upwards of 1500 children’s books.

And we would have been doing that every year for decades and we could plan on decades more. That’s mindboggling. Because in order for that kind of equity to occur, the capacity of the children’s book industry would have to increase by 45% in production.

Even if something implausible like that happened, as Sarah Park Dahlen points out, the context of the industry would still have a profound effect on true voice rising for a POC, indigenous, and/or queer author. So ultimately real reparations could only look like an entire overhaul of the entire system.

I believe the way to create true equity is to do it for ourselves, to step away from this system in the ways that we can and create our own holistic way. We cannot wait for an industry, or a society for that matter, that was never meant to include us. It is only in taking our own voice into our own hands that we can speak our full truth.

I just launched a crowdsourcing campaign that outlines children’s books as a radical act. When we center POC, indigenous, and queer voices and experiences, VOICE IS A REVOLUTION.

I will publish my own voice. I will power share by teaching everything I’ve learned in the industry for 20+ years to my communities, I will mentor and publish other artist/authors, I will strive to change the conversation and move it away from a white frame and focus on our voice, our experience on every level. This is how we change the numbers.

But it’s about more than just books. This is how we heal the impact of generations of silence and invisibility. And that’s why the only reparations I can see are the ones we create for ourselves. Our healing is ours just like our voice.”

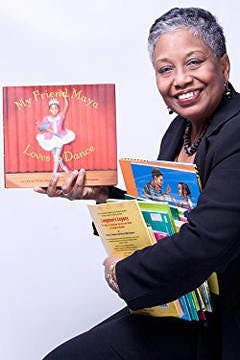

Cheryl Willis Hudson, author and co-founder of Just Us Books:

“I’m sure you’ve heard me say several times, Freedom of the press is guaranteed to those who own one. The quote is not my own (A.J. Libeling wrote it some years ago.) but I believe it applies to the work that we do at Just Us Books.

Suing for reparations makes sense in some ways because only by admitting truths can all of us move forward to correct the mark of oppression that has kept people of color and Native peoples out of and on the margins of publishing relevant books for children.

But trying to get gate-keeping professionals to respond to and publish authentic children’s literature is a full time task that can literally wear you out.

Creating our own works, however, and establishing our own presses and modes of distribution takes us much farther in terms of institution building. The exercise is then also one of empowerment. The learning curve is long and the institution-building is certainly challenging on all fronts, but the end result is definitely empowering and additive in terms of infusing the marketplace with quality, authentic, diverse literature.

Wade and I and the staff of Just Us Books and Marimba Books have worked for almost 30 years to create positive and authentic and empowering books for children — books that may not have otherwise been published by larger commercial presses.

However, they are books that tell OUR story, from OUR perspective. As authors, illustrators, and publishing professions, we must still advocate and demand accountability from the industry at large while we continue to create and publish our own stories from our own presses. It’s too big an issue to neglect from either perspective.”

Zetta Elliott