Is God Racist or Is It My Church?

By Alexis Freeman

Growing up Black in a predominantly White church, I didn’t believe racism angered God. In retrospect, this is no surprise: the standard practice in Christian churches has been to push a message of unity at the expense of addressing deep-rooted issues of oppression. Common narratives within the church often echo the message, “We are all Christians, aren’t we? So put aside your differences. Focus on the goodness of the Lord!”

Consequently, I assumed that racism was outside of God’s realm of concern. How else to explain why my church leaders stayed clear of any discussion of race when Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown were murdered by police and when Sandra Bland died in police custody? I assumed that because my pastor didn’t focus on these issues, neither did God. The message that racism is outside of God’s realm has long been part of mainstream Christian practice in the US. Rather than illuminating and opposing racial discrimination, European Christian settlers used religion to justify enslavement, genocide of indigenous peoples, and land theft. Often times, slave owners manipulated the word of God to protect the institution of enslavement. Others forbade enslaved Africans from worshipping and punished them severely if caught.

Most Christians today would see a deep contradiction in being both a devout Christian and a bystander to slavery. Yet many don’t see the same contradiction in their complicity in contemporary racial violence and oppression. Instead, many uphold oppression through silence on racial injustice. What does the church say about today’s forms of racism and racialized violence?

Unfortunately, most churches answer the question of how to respond to racism and hate with, “Let’s just focus on the gospel. Everything else will fall into place.” This response is eerily similar to that of European settlers and slave owners in colonial America. Ignoring injustice to singularly “focus on God as Lord” runs counter to Jesus’ teachings. His behavior modeled loving everyone equally and wholeheartedly.

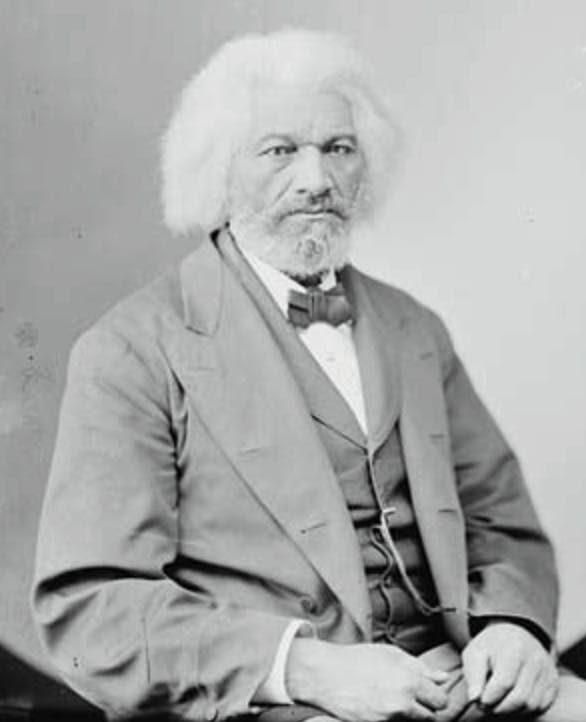

“Between the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference,” wrote Frederick Douglass, a leading American abolitionist and former slave. See PBS for more.

When discussion of racialized violence stops at the church door, the result is an unbearable dissonance for many observant Christians, particularly young black and brown Christians like me. The Christian church, for the most part, hasn’t taken a stand against the most high-profile moral issues of our time — including Islamophobia, mass incarceration, the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). This leaves Christians like me wondering where we fit.

After the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Russell Moore put a finer point on this dissonance and the gulf between Christian practice and Jesus’s teachings: “In a time like this, Christians might ask whether we should, in fact, be angry. Should we not instead just conclude that this is what a fallen world is like and pray for the final judgment to come? If you are feeling distressed and heated, you have reason to be. White supremacy makes Jesus angry.” Indeed, Jesus was angered by discrimination, actively defending the marginalized, including foreigners, eunuchs, and prostitutes. Jesus wouldn’t suggest we ignore systemic and interpersonal racism, and not drawing that connection at the pulpit bolsters white supremacy in and outside the church. “White supremacy makes Jesus angry, but does it anger his church?” Moore seethes the rhetorical question.

I’m now a junior at Amherst College and as EmbraceRace’s intern this summer, I decided to interview fellow travelers — pastors, students, and activists — who are thoughtful about how racial identity and structural racism plays out in religious practice.

Abena Frimpong Bosompem is a senior at Mount Holyoke College who serves on her church’s worship team. She is passionate about including different worship styles in order to reflect and affirm the diversity of the congregation. “If you have a population that is diverse and has different experiences, I think it’s important to have worship songs that are representative of their experiences.” But some have rejected Abena’s efforts. When Abena suggested a worship song in a style that more closely reflects her heritage, there was little interest. When it was time to perform, “none of them sang it,” Abena recounts. “It really frustrated me because [I don’t know] most of the songs we sing but I learn them when we rehearse. I’m willing to learn them.” Some even suggested that she sing it alone.

Reverend Margaret Sawyer, an organizer at the Pioneer Valley Workers Center, and the project coordinator of the Immigrants Protection Project of Western Massachusetts, also voiced the importance of an inclusive church and style of worship: ”People need to feel like they can bring their full selves. And going to a religious worship service is often a really culturally specific engagement.”

In majority white churches, Sawyer continued: “Even if it says on the [church] door that Black Lives Matter, culturally, a congregation has come together in a certain way over a certain period of time. Certain things are done, certain things are not done, and that makes [the church] less open.”

Mexican folkloric dance at church

As a young girl, I didn’t feel I could speak up against racism in my church. I sat in the church pew, under the false image of a white Jesus, listening to a pastor who was silent on the unlawful deaths of Black men, women and children at the hands of police officers; attending sermons that never addressed the racialized violence and disparities in our country; and participating in a worship style that was always the same, geared toward a majority white congregation, only.

I know that favoring a “white” worship style or sermons that don’t challenge racism is usually not a conscious decision made out of malice. Yet when white supremacy is not explicitly discussed, the choice of songs and sermon topics that are implicitly geared toward a white audience are equated with what is normal, universal and traditional. And that lie is another example of how white supremacy is maintained.

In my ongoing journey to address racism and white supremacy in institutional Christianity, I have realized that my initial assumption that God was indifferent to racial violence could not have been further from the truth. I have been so encouraged by others who are committed to actually living the way Jesus did and who are devoted to social justice and healing within and through the church. The Interfaith Sanctuary Solidarity Network, the United Church of Christ, and other churches and national coalitions are speaking out against injustice against Black and Brown people, the LGBTQ community, refugees, women and other marginalized groups. Yet there is still work to be done.

What’s your story? Whether you attend a mosque, temple, synagogue, or church, in what ways are you challenging racism within your place of worship?

Alexis Freeman

Get Insights In your Inbox

Join the EmbraceRace community! You will receive the newsletter with our latest on race & kids, including upcoming events and opportunities, resources, community news and curated links.

Subscribe