I Confuse a Lot of People! A Look at Racial Incongruence

We generally assume that people see us, racially speaking, in the way we see ourselves, that if I see myself as "black," say, or "Asian American," that others do too. But what about people for whom that identity alignment isn't in place? The mixed-race man who is often identified as White? The phenotypically Asian American woman who is "culturally black"? How does that experience of misalignment - or "racial incongruence" - shape a person's experiences and relationships? And how can parents, teachers, and other caregivers support a young person in these circumstances?

Special note: Usually EmbraceRace's Andrew Grant-Thomas and Melissa Giraud co-facilitate these Talking Race & Kids conversations and the guests differ each month. But for this discussion, we changed it up and had Melissa join as a guest. Watch the video conversation to hear discussion and insights from folks who, in one way or another, have lived this reality, and a certain someone who's also done some research in this area. The lightly edited transcript follows.

Andrew, EmbraceRace: So today the topic is racial incongruence by which we mean simply that there is some sort of divergence for some people, between the way they identify themselves racially or ethnically and the way others identify them. That might be phenotypically, how they are identified in the mind of others diverges from how they see themselves. Or it might be cultural … we’ll get into that.

All my guests tonight are experiencing that at least in some context in some way. And the question is, what consequences does it have for them, for their lives, for their outcomes, for the way they think about themselves? How has that shifted over time? What can we do to support the increasing number of people, an increasing number of children who are dealing with a racial incongruence in some sort of way?

For those of you who've joined us before, we're doing two things a little differently tonight.

One, normally Melissa and I, Melissa's my partner in life and in EmbraceRace, and normally we are cohosting this. We've always cohosted this. But Melissa, being one of those people in the circumstance of what we're calling racial incongruence, tonight, will be a guest will be one of our 4 guests, and I will host solo. So that's a difference.

And the other departure is, normally, we would start by introducing and reading a short bio for each of the guests. This time, I'm going to have them introduce themselves to you and also explain how racial incongruence looks like in their own lives. Then we’ll chat a bit and open it up to your questions.

And with that, let me welcome. Casey and Riana, Cindy, Melissa. Welcome, welcome! Let me start, by asking each of you to tell us a little bit about yourself. Anything you'd like folks to know. Cindy, for example, I know you have a book out recently, so for sure share that. All of you, share a little something about yourselves and also let us know, how do you identify yourself racially, ethnically and how you are seen, sometimes or all the time. So let me start with Casey Budd, CBUDD.

Casey Budd: Hello! Very happy to be here.

EmbraceRace: Good to have you.

Casey: A little bit about me. I’m based out of Atlanta, but originally from New Jersey. I am 24 years old. I have a YouTube channel called CBUDD after my name, which pretty much started with me talking about being and identifying as mixed ethnically and racially. I'm socially perceived as white more often than not. So I started making videos about situations and experiences I went through and I got a lot of traction, which I wasn't expecting. But it is now my full-time passion and work.

EmbraceRace: What's your racial mix, Casey?

Casey: Black and white and some Native American. My mother is of color. My dad is fully white.

EmbraceRace:Thank you. We'll get back to that. Riana, what do you say?

Riana Elyse Anderson: All right. Hey, y'all. I'm Riana Anderson. I'm an assistant professor at the University of Michigan and am also, like Casey, I have a black mother and a white father, a Greek father. And so some of the things that I'm going to talk with you about today are not from a research and academic perspective, but also from a personal perspective. My experience is that, if I'm with my Greek father, people perceive me to be a certain way. If I'm with my black mother, people perceive me to be a certain way. It’s also affected by whether my hair is full and curly, if it's straight, if I put bronzer on that day. So it really just undergirds this point that we're going to be driving home today about the contextual pieces that go along with this experience. I'm really excited to have this chat today.

EmbraceRace:Thanks for being here, Riana. And already we’re seeing an interesting and not surprising overlap between what we're calling racial incongruence and mixed race identity. But it's not the same right? Not everyone who is of mixed-race identity is perceived as something other than that, but it happens quite often. And then we have Cindy Wilson. Cindy, tell us what's going on.

Cindy Wilson: Hi everyone! My name is Cindy Wilson and I was born in Seoul, Korea. And I was adopted when I was a baby by an African-American family. They were in the army. So shortly after I was adopted, we moved back over to the states. My parents ended up getting a divorce. And I grew up in Jackson, Mississippi from the age of 7. So I talk a lot about in my book, Too Much Soul, about how that's when I realized I was different, by people picking on me just because of how I looked and how people responded to me and my family.

Growing up where I did in Jackson, Mississippi, there were no other Korean people so everybody called me Chinese. I had to do a lot of correction, or sometimes I just didn't even bother! Now I live in Atlanta, which is more open – it’s really exposed me to more Korean people and culture. I was also on Casey's YouTube. And you know, so she talks about her dynamics as far as race and so she asked me to be on the show. So it's interesting seeing what people would put in the comment section about their perception of just me talking about my life and how they would kind of want to put me in a box of like, "Oh, she thinks she's black!" And I'm like, "No I didn't say that.” I'm Asian. But culturally, I'm heavily influenced by black, African-American culture. Excited to talk today.

EmbraceRace: Yeah. It's good to have you, Cindy. And Melissa, let me ask you about your background which I happen to know. But in addition, you can get started on sort of the next question which is, give us a little insight into what difference it's made for you, this sort of disjuncture? I know it has definitely affected your sensibility about things.

Melissa Giraud:Hi, y'all! Thanks for coming on and for joining us. Andrew sprung this "you're a guest thing" on me (and I kinda like it!). So I am the child of immigrants. My mother is French Canadian (white), my dad from a little island called Dominica and he's racially you might say a light-skinned black man, or you might say racially mixed - depending on the context. Certainly in Dominica he was made fun of for being light. In terms of how I’m identified, lately, I get a lot of "white," right. But growing up (and even now), it really depends on the context and who I'm with. It was different in the context of the neighborhood I grew up in as well, which was a neighborhood of color. And one of the issues for me as a child of immigrants is that, as I eluded earlier, race is different in different countries, so in your parents’ experience, this black/white thing, which is all it was when I was growing up, is American. And we're actually Dominican Canadian, not living an assimilated experience. So there is sort of a way in which you don't get the language and context you’re dropped into because your parents are learning it as well. So I'll stop there.

EmbraceRace: So you know already we've started to get into a little bit but tell me, tell this audience, what do they need to know given your experience? For those parents, for example, who maybe have a child in this circumstance or who have children who will probably find themselves growing up with something of the experience you're starting to get at. What do parents need to know? You know, what was challenging? What was interesting? What have you had to navigate because of that?

Cindy, go ahead. Let's start with you.

Cindy: Okay. For me personally, having been a part of a transracial adoption, I think what really would have helped me would have been more exposure. Until I got exposure, I never really wanted to go back to Korea. Until I moved to Atlanta, and I've been here eight years, I never wanted to go back to Korea. But because I've been more exposed to the food, the culture, and the people, it really has made me want to learn more about my heritage. So I would definitely say exposure.

And then there's a huge opportunity like since I came out with my book, I've met a lot of Korean adoptees - I didn't even know this huge community existed. There are so many organizations for transracial adoptees. And also organizations like EmbraceRace that can support parents and others to guide kids around racial experience and understanding in a range of situations.

I also think parents definitely need to get more involved in the school system. So meeting a lot of other Korean adoptees and others who stood out for their appearance or difference at school and hearing how they've been teased a lot in school. There's a huge disconnect and many school systems are not supporting students through. So many of us experience that and become traumatized. That typically starts at school.

EmbraceRace: Cindy, you mention teasing and you related appearing on Casey's show and reading comments saying you know, "She thinks she's black". And you're saying, "No, I don't think I'm black."

Cindy: You get the opposite, too. Others are very supportive. They're like, "Oh she's a sister," you know and I'm like, "Yeah I'm a sister but like I'm not black." Like I recognize that racially I'm not black, but my family is black. And that was a huge influence, growing up in the South and having a black family and a lot of my friends being black, like that was a huge influence on me. But then you know people want to put you in a box just based on how you look. I had to deal with a lot of that and being on Casey's YouTube, seeing the comments, confirmed that it's just hard for people to accept or even grasp that other people can have different experiences.

EmbraceRace: Casey, you have black and white biological parents. So do you, Riana. But Casey, I think you're already said you really grew up with sort of the black side of your family?

Casey: Right. Yeah. I barely know my dad's side. They're very distant. So I grew up predominantly around the black side and, overlapping with what Cindy said, I didn't really realize how much of a shock that was to other people until I got to school and I was culturally you know more knowledgeable on “African-American things” than other things and kids were like, "You look like a white girl. Why are you wearing Rockaware?” or whatever. Stereotypes really.

So I would say if there was a challenge or something to maybe improve on it would be somehow getting parents more involved with the school and educating kids on how different isn't bad. Teaching them that just because you don't understand something doesn't mean you should dismiss it. That's been the story of my life to this day. When I do tell people I'm mixed or black and white it's like, "Oh, no you're not!" It's just like an immediate dismissal. So I think if we were to try to unlearn that. [Or never learn it at all – EmbraceRace.org!]

EmbraceRace: And Casey, you said in an earlier conversation, I remember you saying that high school is when things really sort of came to a head for you on racial identity stuff. Do you want to say a little bit about that?

Casey: Yeah. My overall friend group was really diverse. My actual high school was probably predominantly kids of color. But I got a lot of the comments of like, "Oh the white girl's hanging out with all the black girls," or something along those lines. It became a strength towards the end of the high school years but in the beginning it was really hard because I kind of didn't fit. I kind of could go anywhere and that could be a good and bad thing in different scenarios. Now I am glad for the experience because I feel like I understand people a little bit better for it, if that makes any sense.

Melissa: That does make sense!

In terms of how to help kids going through this, I have some thoughts. So my kids [they are also Andrew’s kids!] are generally perceived as black biracial. One of them sometimes identifies as black, the other as biracial. You know, it's still in flux. They're 8 and 10. So they don’t have the same incongruence I have.

But I like to tell them that when it comes to race, you have a social identity – how people see you racially. And you have a self-identity - how you self-identify racially. This is true of other aspects of your identity, too. And they both have consequences. For some people, social and individual identity are the same thing. But for some people, like your mommy, they're not always the same. This helps us talk about the interplay between your social identity and your self-identity racially. Also, Cindy and Casey talked about racial incongruence, that experience of being really confusing to people, racially. I want to underscore that with an analogy.

I have a friend who told me the story of her female friend who was dating a man and found out a couple dates in that he was trans. She was surprised but she embraced the relationship and they continued on happily. But what was interesting was the person telling me this story about her friend’s experience and her response to it. She said, "And I'm so confused. Does that make her a lesbian, because her partner was once a woman?" My friend, an onlooker, was really struggling with the categories. A light bulb went off for me where it was so parallel to the experience of, "No no, no. You can’t claim that racial identity." You know, “you're basically white or you're basically black," you know. People just want to put you in a box because it makes them really uncomfortable for these binaries not to exist.

Community Q&A

EmbraceRace: Thank you for that. And Riana I want to come to you, both your own story and the health piece, the health research. But this is also a good place to insert a question that came in. And it's from Lauren and she wonders "What is your best response when folks reject what you tell them with respect to your racial ethnic identity? What do you say at this point?" Riana?

Riana: You're going to give me 4 questions at once.

EmbraceRace: Yeah!

Riana: All right. Cool. Thanks Andrew.

I do want to make sure that we're getting to this point of incongruence which is, you know everyone is touching on I think various elements. So what's really important here is exactly that point that as Melissa has brought up, I'm telling you what I think that I am and what I perceive myself to be. You're seeing something else and now you're rejecting that thing. Socially that might be one thing if I'm in high school, like Casey was saying. And a group is like, "Nah girl, you're not that," and you're like, "But I am," and you're going to feel a certain way. You're not perhaps going to be able to hang out with them. You're not going to be able to go to some of the same dances or whatever. That’s one aspect.

But Andrew you were asking about the health component and there are some very real consequences that come from folks being labelled differently. And typically what the health research says is that folks who are labeled as black typically, or have darker skin generally, receive worse care. They receive shorter times being seen by the doctor. Doctors are less likely to prescribe them medication for pain. There's so many things that come with being of darker skin.

And so to some of these earlier points, the advocacy is what's really important. You're looking at your child. You think that they're the most beautiful person on the planet and that's wonderful. And you have to put on a lens of, how might other people perceive my child? If somebody looks at their hair and it's got some kink to it, if they have a darker skin tone, my child might receive differential treatment. And I have to advocate when I'm in that doctor's office, when I'm in that school because bias is going to play a role in the way people are treating my child. They're going to see them as incongruent with how my child might see herself, how I might see her. And that means I need to advocate as a parent and that also, as everyone has been saying, need to talk to my child explicitly and ask, "How do you see yourself? How might it feel if other people see you differently?" Those really emotion-based questions to start to process how it might be different for them in a world that, to Melissa's point which I think was beautiful, is just trying to put them in one place, is not content with them being as they are.

EmbraceRace: That's a great point, Riana. Cindy I wanted to come back to you, we have a few questions around transracial adoption and one of them is from a woman who is herself a transracially adopted Korean, right.

And I know that most Korean children who were adopted by U.S. families were adopted by white families. And this is an interesting, right so you're adopted by a black family. And I think it's fair to say, although you know I'm going more from my gut than from any research, that it seems that there is more sort of social distance between black Americans and Asian Americans than between any other sort of two groups of color. Right. It feels like it would be a different experience to be a Korean girl right adopted by a Black family than by a white family. So I wonder, you know, or I'll read her question. She said, "Can you address transracial adoptions? I'm a transracial Korean adoptee parenting half Korean kids in a predominantly black school. How do I help them find their racial identity without erasing their Korean-ness when I hardly know Korean-ness?"

Cindy: Right. So I can definitely relate to that because my mom, she really didn't tell me or teach me a lot about Korean culture. Probably when I was going into junior high, she gave me these tapes of how to speak Korean! And I was like, "I don't know what they're saying! Who am I going to speak this with?" Like I said earlier, what could have helped me was having more exposure to like Korean culture and heritage but I just didn't have that in Jackson.

I think what really helped me was the fact that my mom is a very confident individual and she makes no apologies. So she never, when she would introduce me be like, "This is my adopted daughter." She always referenced me as her daughter. And then Jackson was smaller too. And so they knew my family, like my mom, my grandparents already had an established name so they knew them. So it wasn't really that big of a deal in Jackson because everybody knew everybody. And so, it's interesting now that I've written my book. I went to Jackson State University, which is the HBCU. I have friends now that are like, "I would see you on campus and we'd all be like who's the Asian girl? Who's the Chinese girl?" Everyone called me Chinese. "Who's the Chinese girl?" But then they never really questioned or asked me anything.

There was someone in the chat who said “I raise my children to be kind people, to be good people.” But that’s not enough. So I think for other people, kind of on the other end, I think it's important to ask questions to gain understanding. So kind of like what Melissa had referenced with the transgender analogy, I have questions about it. I'm not very clear on it. But I think it's very important to be respectful of race and other people's situations and to ask those type of questions.

And, again, the exposure piece of it is very important, too. I had so many identity issues growing up. And the bullying that I would receive. It would have been helpful to see images that looked like me, too. Something like the movie Crazy Rich Asians - positive images that I could see and like. Now there are a lot of documentaries, films, and like I said earlier, groups that support people that are going through different situations as far as like transracial adoption. So you expose them but then your child has to be comfortable with it too. If they don't really embrace it and want to understand that at the moment, let them know that the door open for them when they're interested.

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Cindy. Now I want to sort of try to collect some of your wisdom for parents whose children may be struggling. You talked about bullying just now Cindy and still getting comments from people. You’ve mentioned other struggles with your particular identities. And you all strike me as, you know, coping very well! My guess is that you have all traveled that distance.

Obviously you are more experienced with this incongruence now than you were 15 years ago. But I'm also wondering if, in addition to the sort of various kinds of exposure you've talked about - exposure to role models, exposure to culture, where that may be appropriate, advocacy you talked about - the importance of having parents and others who advocate for you. I just wonder if there is you know a particular sort of nugget of wisdom about the work that you can help children do to get to a place where they're more confident and secure in their identities. Melissa, can we start with you?

Melissa: Sure. We [Andrew and Melissa, cofounders of EmbraceRace and co-parents] do this all the time and I do this in particular with our kids.

First, there's so much about race that doesn't make any sense! And people who are racially incongruent are great examples of that. They expose the lie of race in a way. Our kids are 8 and 10, and I like to point out the many ways in which race doesn’t make sense, asking questions. "But why is this person ‘black’ when they're lighter than this person who’s ‘white’?" All this stuff. Or "This person looks Southeast Asian but they happen to be from Croatia. How did that happen?"

And you just have to say, "Well look, race was created to divide us. And it actually doesn't make sense. Like if you sort of lined people up by color where would one race begin and the other end? What you would also see, as Riana discussed, is colorism. You'd see all sorts of advantages - we talk about that with the kids, too - accruing to the lighter-skinned people. And that's a real thing in terms of the tension we feel as people in between, particularly people who are part white. Because we do, we are advantaged in a white supremacist system or systems. But I think that just showing those examples of it not making sense, wherever they are, can be funny because they expose this lie.

EmbraceRace: It's not you. It's us.

Melissa: Yeah. And I think you have to, in that context, also talk about the colorism absolutely. You really have to because they're exposed to movies where all the Black actors happen to have a non-black parent. I mean I'm exaggerating but not totally. The “black” actors we see are almost 100% light-skinned and with looser curls, so light or mixed. [Of course, most of "black" America is mixed because, well, slavery.] Try it - if you look up actors in mainstream, Hollywood movies, you’ll often learn, oh gosh, her mom's Guatemalan or White. So you really do have to ask the question, openly. “Why is she considered socially black if her mom's white, for example?" Did the “one drop” rule ever make sense?

And always, when talking to kids, you have to start with where they are, what are their questions, what do they understand? Ask them questions and challenge and guide them. I mean it really depends on how far the kid has walked down this road. We've been having these discussions (with our kids) forever.

EmbraceRace: You know what this makes me think of...

Melissa: What?

EmbraceRace: What this makes me think is, for folks who've gone to college and studied race in college, you know, the first sociology course you take, you learn that race is socially constructed, meaning we made it up. It is not genetically based. There's nothing essential about race and racial identity. And yet we don't act like that, right? Including those of us who talk about race all the time, people who teach about race, we don't act like it.

What I hear you saying, Melissa, is in a way, at least in what we say to our children, can we impress upon them again and again and again how constructed it is, right, how nonsensical it is, and, therefore, how to try certainly not to be limited by it.

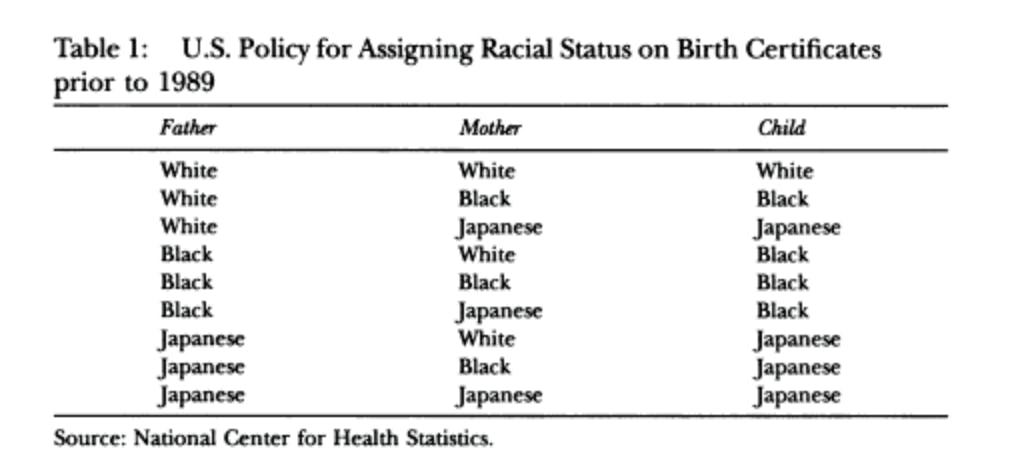

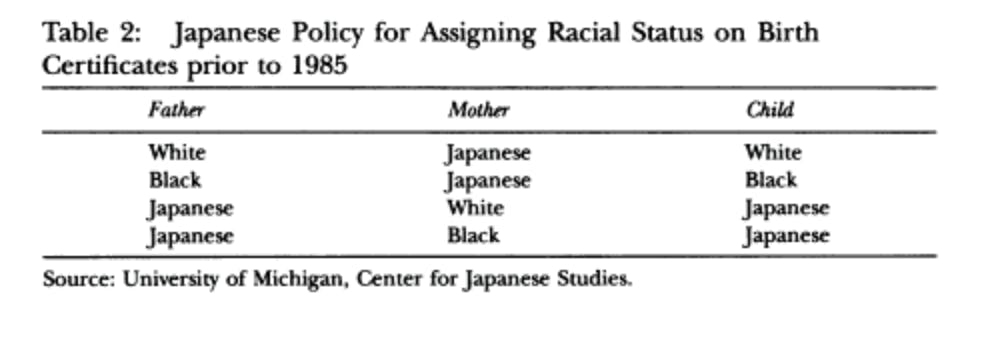

Riana: I think Melissa's point was so great. I was just sharing a resource on this in the chat. Public health research Thomas LaVeist wrote an important paper about this. (See: Beyond Dummy Variables and Sample Selection: What Health Services Researchers Ought to Know about Race as a Variable.)

Riana: Essentially, Dr. LaVeist looks at the criteria that have been used to assign race at birth in three different countries - the United States, Japan, and Brazil (see charts from his article above). And they have three completely different ways of ascribing race. So you can be white in 3 completely different ways in these different countries. So it just depends on where you happen to be born is how you can be called white. And in one case in the United States, it just changed in 1989: there were 8 different classifications but only one way to be white, which is that both of your parents have to be white. So for just about everybody else, it would be depending on your mother. That would be what's written on the birth certificate but only if you had a white mother and a white father were you able to be white.

And so I think to Melissa's point, this protection of what the privileged group is has been so evident in American history that we have to be able to explicitly talk to our kids about not only is it constructed. But also, we've been acting it out and this is what privilege looks like and this is what oppression looks like.

EmbraceRace: Right. OK, here are two related questions. First, I want to ask, what do you wish your parents had said, or maybe they did say, to your teachers when you were in 3rd grade? Something that would have made the school experience of racial incongruence easier. Relatedly, Alan asks, how can teachers help, what would you say to teachers? I know Riana, Casey and Cindy don’t have kids but if you could speak from your experience.

Riana: Well, in the work that I do as a psychologist (and this is how I met these great folks at EmbraceRace) I have a program called EMBRace, which is all about how do we engage with, manage, and bond through these really challenging topics of race. So it's really literally all about talking about race. I'm a psychologist. I talk, y'all can hear it on here. I talk about race all the time.

To Cindy's point earlier, it’s not enough to say we want kids that are good, that have good morals and values. But you can read in Dr. LaVeist's paper about what happened with those good Christians who were able to justify Africans as not being human and were able to have centuries of slavery. Like that's what we're going to get if we have people who just say "Let's do good things. Let's have people who can help us do our good work and we'll declassify an entire group of people based on those metrics." Right?

So we can't just say, “Let's do good things. Let's raise good kids.” We have to pop the hood on race and say: “Listen kids, listen teachers of my kids, listen babysitters of my kids - I'm not playing with you about how my kids are raised. This is the standard by which we talk about race. If you're afraid to do that, we need to figure out a different care system for my kid. We need to go to another teacher. That's just not acceptable. We need to be congruent as parent and teacher, as parent and parent, as anyone around my kid. We got to be congruent. Imma put you on EmbraceRace so you can listen to these great people! Here are these resources that exist so that we can be congruent as caregivers to my kids.”

Cindy: Yeah, I agree with Riana. Like I talk about in my book, the people who say "I don't see color" and think that’s a good thing. Instead, when you don’t see color you're denying that person like who they are.

EmbraceRace: Thanks for that. We actually have a question that digs into that a little bit. I'm going to put you on the spot, Casey, because I know that you have siblings who are darker than you. Bethany’s question is: "When my white and African-American daughter, as a mixed race black white daughter, tells me she has the same colored skin as me, which is white” – so the mom is white - “do I just agree with her and let her label her color however she wants to, or do I insist that she's a little bit darker than me and explain that she's half Caucasian like Mom and half African-American like Dad. I've been doing this. Now her little sister, who has the same 2 parents, is a little darker skinned than she is. How much do I let them say and think whatever they want and how much do I try to direct their thinking and vocabulary?"

Casey: It's a great question. Well, personally, I have two older brothers. The oldest is probably the one that would you would see off the street and say, "Oh, he's African-American." The other one, he's kind of my skin color tone, but still looks like some type of color. And then there's me who could look anyway any kind of day.

I don't have children, but I would say that kind of piggybacking off of what everyone has said, I think exposure. I think it is important to educate the children on their background, on what Dad is and what Mom is. And if you're identifying as this right now, that's not to say that might not change with some education. I can't imagine growing up and not knowing. Because my mom is very fair skinned and for me to not know, it would feel like not being my whole self and not knowing myself as well as I do now. Having that conversation and having in-depth conversations kind of like Riana was saying emotional questions like "How do you feel and have you been in this scenario and how does this make you feel? Have you been questioned by these kind of people? What do you identify as when this happens?" I think having those conversations can lead to more self-identity knowledge. My mom kind of embedded the idea like, this is your skin you're in and you should love it no matter what anyone says. That's like been her motto since I was... for as long as I can remember. It's not going to change so you might as well love it. I think having those conversations helps the children really “grow into their skins.”

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Casey. Melissa, did you want to go?

Melissa: Yeah, I didn't catch the ages of the children in the question but I do agree that exposure to people who look like them, to families like theirs and to people underrepresented groups is really important. So exposure through who comes to your house and what you have in your house, all of that. The books, the toys, media.

And I want to stress that this is true for all kids. since we really live in a world that's so white dominated and that’s true evident in the culture we consume. In order to counter that white supremacy, the constant message that we care about these people more than others, all kids need exposure to lots of folks of different colors and cultures.

And one way to start is to have the conversations with littler kids about skin color is, for example, buy some of those skin color crayons and sort of notice skin color and notice Mommy's and notice Daddy's and which crayon is closest? And I'm going to draw you. You're going to draw me - so that you're commenting on and loving their color.

The place you have to move to, as Riana and I were saying earlier, is not just like, “Oh it's all great, this is your color. Love it.” But also, you need to know this other thing, that there is this hierarchy, this racial hierarchy (don't say it exactly that way) that we counter so that we can feel good about ourselves, but also so we can believe in the worth of all people, right. (We counter the hierarchy in conversation, in our action, in the choices we make.)

For example, when our kids were wanting white dolls, I told them, "You know, well the thing is that there are so many white dolls and so many white TV shows and so many this, that it can make us feel like it's better to be white or to look white or to be light. And so that's why because our brains do that, kind of trick us when we see all of that, that's why we sort of try to make it right by, for example, choosing dolls of color in our home." And so lots of dolls of color. Increasingly, they get excited when there's a dark-skinned doll because they've noticed that the dolls of color are often very light if they're of the black/brown persuasion. And then recently, after years of building a good collection of non-white dolls, my daughter recently was talking about future gifts she’d like, and she was sort of embarrassed to ask me, she's like, "Can I have a white doll?" It was just this very funny moment because we just don't have that many white dolls, we don't! And she's sort of like these are all great but can I also add this one? And I was like finally comfortable enough, because we'd done so much work, that I'm like, "Maybe?" You know what I mean! It's something we're working on.

EmbraceRace: Thank you. Thank you. Of course we've opened it up. Questions are pouring in. Let me jump to another question and it does get to, you know a mom whose struggling a little bit. And this is what Beth says: "I have a super woke 14-year-old daughter. I am an adopted Korean American and her biological dad is white. She's gone to predominantly white institutions for her whole life until now, her freshman year of high school. She goes to a “minority-majority” school now. She loves it and is really struggling with her white side. She makes tons of white jokes targeting white people as ignorant oppressive, etc. And she says she is embarrassed by her white side. Can someone on your panel talk to the issue of internalizing racism in two directions both against herself as a person of color and against herself as part white?"

Cindy: I would probably say I would probably ask the child more questions. Like, where is she getting that narrative from? Is it based off of an experience that she had or friends that she's having that are saying certain things? Because I had a situation when I was in high school. Like I had all different types of friends but I could never hang out with them all at once. Like I had Asian friends, white friends, black friends. But just trying to mix them together, it didn't quite work. But I mean growing up like when I was hanging out with my white friends, my mom would sometimes say, "Well you just need to be careful because you can't trust white people." So she placed that narrative in my head. And so like you're kind of looking for it and then when somebody (white) betrayed my trust, then it was like, damn, she's right! You know I can't trust white people.

And but I don't think it's necessarily a bad thing that she feels more of a connection to one group of people. There's something about that group of people that she yearns for and that she feels that connection with. But I had to learn, too. I mean sometimes I realize I can still have those biases, thinking that all white people are entitled, all white people are this, and you know I have to catch myself and remind myself not to lump people together based off of their skin color. We all have our biases we need to be aware of. I'm sure her [the questioner’s] daughter has moments where people put her in a box. So she needs to learn not to do the same thing.

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Cindy. And you know we get this question quite a bit. But essentially it is, what does a healthy white identity look like? Especially a healthy, anti-racist, racial justice identity, an affirmative one that's not simply about not doing these other things, not being a certain way but actually being very a positive affirmative way. Riana, Casey, and Melissa, you all have one white parent. I wonder if you can relate to a period of time when you struggled with that whiteness.

Riana: So what Cindy was just addressing is the work that I do, what's called racial socialization, the way that we socialize kids around issues of race. And there is a whole area within that about how we promote mistrust to kids, especially when we talk to kids of color and we say, "white people X Y Z."

So whenever you start any topic with … “This entire group of folk do X Y and Z …” we found just incredible anxiety and depression symptoms that map onto that for kids. So you are scaring the mess out of your kid in whatever direction you talk. And someone asked this question in the Q & A, when you other folks. When you say, "This entire group of people are X Y and Z," remember it’s more than likely those kids are going to have a teacher, see somebody on TV, have a friend, who maps on to that.

So particularly if you're like me, growing up in a house which was incredibly Afrocentric. I was with a black mom, like hella Maasai warrior stuff on a wall and books and like kente cloth, all that. And then I have a mom, grandpa etc. who's talking about, "Well, the white man X Y and Z." So then I go to see my dad and I'm like, he is in fact a white man, like, how do I negotiate this, right?

So my advice, regardless of whatever group you're part of, is that the way to form a great identity is to be excited about who you are, excited about who your folks are. So my dad is Greek. We do a lot of cultural exploration, so as much as white folks may know about their culture and their heritage. That's absolutely fantastic to celebrate Irish, English, Greek identity. Like that's fantastic and wonderful, and you don't have to do that at the expense of anyone else. You don't have to diss folks to embrace yourself. So really focusing on the great things about self. And if there are specific things that you're concerned about specific folks say, "I've had this experience and that makes Mommy or Daddy feel this way about this group. What do you think about that? Does that make sense to you? Do you think that that's silly?" Like really getting into that emotional piece of how can I pass on some of my concern, my wariness around this without scarring my child to pieces.

EmbraceRace: Great advice both of you. We're almost out of time and I want to ask one more. I just want to make sure Casey, if you wanted to come in, please do.

Casey: Pretty similarly my dad is white and my mom has made the comments like "white people this," like how Cindy was saying. And growing up was a little confusing because, "I'm like, Mom, aren't you half white?” But she was raised by a black mother and doesn't know her father who is, we don't know, of some lighter shade. So she all she knows is pro-black. And so it was a little confusing. I think like you're kind of saying, like knowing your own identity and growing into your own identity kind of helps to navigate that. And I have a pretty great relationship with my dad, so it didn't really truly affect us too much. And I've grown into my power of being biracial. Instead of letting it hinder me, I kind of try to find a way to always let it empower the moment rather than destroy the moment. If I can educate, I will. You know, if there's a difference or there's a gap or there's a misunderstanding like let me not get mad or upset. Let me try to educate this moment or let me try to learn, either way.

EmbraceRace: Thank you for that. Here's the last question. And it's from Dana, and Dana says, "Is there a place where we can find stories about characters who are mixed race and look incongruent? I'm not sure what that would mean exactly but stories about characters who are mixed race. I want to expose my kiddo to others who are like her.” So this is a exposure issue of Cindy especially was naming that. And specifically, Dana says: "expose my kid to others who are like her as much as possible, i.e., white-presenting, biracial girl with a black mom and no dad."

Melissa: The Marisol McDonald series of early grade books comes to mind although it’s not exactly your circumstance. It’s about a biracial, bicultural family and specifically about a girl who’s often told she doesn’t make sense – racially, culturally and otherwise – and her response is great. (See Related Resources for a link to this and other such books. Please let us know of other finds in the comments.)

EmbraceRace: Go ahead, Cindy.

Cindy: Well, she was very specific about what type of book that she's looking for. And if you're not able to find those books, make them. I didn't wait on a literary agent or a publisher to like get my book. I just self-published it because I just wanted to get my message out there. These days there are a lot of resources for that. If that’s the story that you want to be able to put out there so your child and probably other families will be able to relate to it as well. Because there just aren’t a lot of those examples out there. So that could be one consideration.

Related Resources

Beyond Dummy Variables and Sample Selection: What Health Services Researchers Ought to Know about Race as a Variable.

by Dr. Thomas LaVeist

When "racial incongruence" is used in the public health field, it refers to the inherent problem of using race as a variable in research when race doesn't hold together as a consistent category. As LaVeist writes: "Although often used in health services research, race is a poorly understood concept because it lacks conceptual clarity. Moreover, the measurement problems with race have not yet been adequately addressed. As a result, many quantitative models that attempt to explain race differences are inadequate to inform health or social policy."

The American Psychological Association's RESilience Initiative

This is the APA's racial ethnic socialization (RES!) initiative that includes resources for parents. For more about the initiative, check out the Talking Race & Kids conversation we had with its leaders: Managing Racial Stress, Guidance for Parents.

5 Things to know if you love a mixed race kid

by Sara-Momii-Roberts for EmbraceRace

Although being mixed race and being racially incongruent are not the same thing, there is a lot of overlap and this piece definitely talks about both.

Same, Same, Different: Creating an Inclusive Kindergarten

by Madeleine Rogin for EmbraceRace

Great piece about helping young kids value difference and think beyond binaries.

Children's Books Recommendations

There aren't many books that explicitly talk about the lived experience of racial incongruence, i.e., being racially unseen, misidentified or confusing to others. In fact, most of the following kids books (recommended by ER or by the ER community in the chat) don't explicitly talk about the experience of racial incongruence, but they do make room for the conversation. Please add your recommendations in the comments!

Marisol McDonald Doesn't Match (Ages 4 to 8)

Written by Monica Brown, Illustrated by Sarah Palacios

Try as she might, in a world where everyone tries to put this biracial, Peruvian-Scottish-American girl into a box, Marisol McDonald doesn’t match. And that’s just fine with her. (Ages K-3. Part of a series.)

Recommended by EmbraceRace

Real Sisters Pretend (Ages 4 to 8)

Written by Megan Dowd Lambert, Illustrated by Nicole Tadgell

This story was inspired by the author’s own daughters, whom she overheard talking about how adoption made them “real sisters” even though they have different birth parents and do not look alike. She also wrote an EmbraceRace article about the experiences that informed the book.

Recommended by EmbraceRace

Charlie and Mouse series (4 to 8 year olds)

Written by Laurel Snyder, Illustrated by Emily Hughes

Join Charlie and Mouse as they talk to lumps, take the neighborhood to a party, sell some rocks, and invent the bedtime banana. With imagination and humor, Laurel Snyder and Emily Hughes paint a lively picture of brotherhood that children will relish in a format perfect for children not quite ready for chapter books.

Features what could be read as a mixed race family. Mom appears white and Dad appears Asian or API, and their two boys appear to be a mix of the two.

Recommended by EmbraceRace, H/T MDL

This One Summer (YA graphic novel)

Co-created by Jillian and Mariko Tamaki

Every summer, Rose goes with her mom and dad to a lake house in Awago Beach. It's their getaway, their refuge. Rosie's friend Windy is always there, too, like the little sister she never had. But this summer is different. Rose's mom and dad won't stop fighting, and when Rose and Windy seek a distraction from the drama, they find themselves with a whole new set of problems. It's a summer of secrets and sorrow and growing up, and it's a good thing Rose and Windy have each other.

Features a protagonist whose dad seems Asian and mom seems White, making her a blond, biracial girl. Her friend also seems like a child of color, but there's no definitive discussion of this. And another secondary character seems to be First Nations (it's set in Canada).

Recommended by EmbraceRace, H/T MDL

All About Clive series & All About Rosa series (Ages 3 to 6)

Written and illustrated by Jessica Spanyol

Board books that promote gender equality, challenge gender stereotypes and celebrate inclusivity. Also these books are not racially explicit, they do feature kids whose racial identities can be read multiple ways, making room for all kinds of difference.

Recommended by EmbraceRace, H/T MDL

Color Me In (Young adult - not yet released but available for preorder)

Written by Natasha Diaz

Growing up in an affluent suburb of New York City, sixteen-year-old Nevaeh Levitz never thought much about her biracial roots. When her Black mom and Jewish dad split up, she relocates to her mom's family home in Harlem and is forced to confront her identity for the first time.

Recommended by a community member in the webinar chat

"More, More, More," Said the Baby (Ages 1 to 7)

Written and Illustrated by Vera Williams

From beneath the tickles, kisses, and unfettered affection showered on them by grownups, the children in this book cry out for more more more! The stars of three little love stories - toddlers with nicknames like "Little Pumpkin" - run giggling until they are scooped up by adoring adults to be swung around, kissed, and finally tucked into bed. Features diverse families.

Recommended by a community member in the webinar chat

Riana Anderson

Casey Budd

Cindy Wilson