Hello. Im a Person. What Are YOU?

Race, humanity, and what I learned in high school.

By Andrew Grant-Thomas

About three years ago I saw an old friend in Boston. We had dated for about a year in graduate school, when we were in our mid-twenties, and on my visit she showed me photos of ourselves from two decades earlier.

“My God,” she said. “We were so young.” Her voice was full of awe, verging on incredulity. As if, over time, she had dismissed the possibility that we — she — could ever have been as young as the couple in the photos.

My response was a little different, more Shock than Awe. The younger me looked handsome. Attractive. Not just in a young-people-are-adorable kinda way, either. I’m talking total hottie.

Who knew? Not me when I actually was that guy, tell you what. A weird discovery to make so long after the fact. And here’s the other thing I realized in the moment: While I don’t see photos of my young-adult self often, I’m similarly surprised every time I do.

What’s up with that?

Invisible Me

I think it was in my junior year in high school that a White classmate — call him Bob — said: “I’m just not attracted to Black girls. I can tell when a Black girl is objectively pretty, but I just don’t find them sexually attractive.”

I don’t remember the context. It might have been prom season.

Bob and I went to a predominantly white private school in New Haven, Connecticut. A lot of Yale professors’ kids went to my school.

Through high school, as a straight, Black guy, I had no sense of myself as someone girls might be attracted to. I didn’t think I was unattractive, exactly. More that I didn’t see myself registering romantically with the girls and young women around me. It wasn’t that they graded me poorly; it seemed that they didn’t grade me at all.

In retrospect, I felt the way I imagine “black girls” might have felt in a world chockful of Bobs.

My partner, Melissa — who is biracial — tells stories about how I played “hard to get” when we were first getting to know each other. My usual retort: to point to our two daughters, hand-wave at our house and other mutual “entanglements,” and offer a smug, I-dunno-I-think-I-played-it-just-right shrug.

But my truth is different than her story or mine. I thought Melissa was fabulous (still do), recognized her attention, and wasn’t trying to play at all. I think I just didn’t have the healthy ego apparatus I needed to interpret her attention as romantic interest.

I blame my dull receptors on what I learned, and didn’t learn, inside and outside school as a kid. I blame a lot of it on the interaction of race and class privilege in a mostly-White private school in the early-1980’s, and in the hearts and minds of all of us socialized there and then.

For a teenager, one’s peers supply the feedback that matters most regarding judgments about interpersonal appeal. In retrospect, having gone to mostly-white schools from the day I arrived in the US from Jamaica in the 1970’s didn’t help. Nor did it help to be a work-study kid at a 7th–12th-grade school with a lot of well-to-do White kids, including girls, in the company of whom I often felt invisible.

It wasn’t until the end of high school — thank you, dear prom date/first girlfriend! — and then college that I began to realize that some women might be attracted to me. It was much later still that I began to think of myself as a more or less attractive person.

Racial Friendzoning

At age 14, 15, 16 I didn’t have the language for what I felt in high school, or even a name for Bob’s dismissal of an entire racial group of people.

In 1991, Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever drew attention to interracial dating, with particular attention to sexual attraction between Black and non-Black people. Then yellow fever came along in reference to some non-Asians’ preference for Asian partners, and especially for (East) Asian or Asian American women.

(I’m not aware of any popular label for cross-racial attraction to Latinx, White, or Native American people. Are you?) But fever, in this sense, is something like the opposite of what I’m talking about. I’m talking about “friendzoning” an entire racial group. What do we call that?

Some call it racist. Others disagree, including, not surprisingly, those who do it. I came across an article about the phenomenon, which one Facebook commenter called racial friendzoning. (I’ve since learned that among researchers the term is sexual racism.) Another commenter, a young White woman, wrote this:

"As someone who has been accused of being a racist dater [the article] was interesting to read. I am Caucasian. I have absolutely no sexual attraction whatsoever to Caucasian men. I am completely open to friendships, business relationships, etc. with white men, but the thought of seeing a white man naked is not sexually appealing to me. I still think white men are capable of love and by no means do I think my sexual attractions make me a racist person. I don’t agree with someone suggesting that my lack of sexual attraction to a certain race makes me a bad person. I do however find the whole concept interesting and am curious as to why I am sexually repulsed by my own race."

Some would say that a person of color who rejects same-race partners as a matter of course suffers from “internalized racism.” Does the same diagnosis apply to a straight White woman who admits to being “sexually repulsed” by white men? If it’s fine to rule out people romantically on the basis of racial identity, is it also okay to rule them out for employment or club membership or housing or friendship on that basis?

Which gives you a bigger case of the heebie-jeebies: someone who excludes all members of a racial group from romantic consideration or someone exclusively attracted to members of a group to which s/he doesn’t belong? Or do both fall in the category of “personal preference,” deserving neither our scrutiny nor our judgment?

Dehumanization

To me, the word that comes to mind is dehumanizing, the denial of humanness to other people. To rule out an entire group of people from romantic consideration on the basis of race is to dehumanize them.

Whoa! Whoa! Whoa! Some of you just threw up your hands.

I get it. For many of us, the word “dehumanization” brings to mind iconic horrors. The murders of more than 1 million Jews and other “enemies of the state” at Auschwitz alone in WWII. The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service from 1932 to 1972. The slaughter of some 70% of the Rwandan Tutsi minority over 100 days in 1994.

Few of us recognize our own impulses in such obscenities. My wise friend Courtney notes that we often define terms like homophobia, misogyny, racism, and dehumanization with reference to behavioral extremes. But, importantly, it’s in the middle spaces of mass behavior — the less dramatic, typically unremarked, routine and ostensibly private practices— that these aversions take root in the culture. Or not.

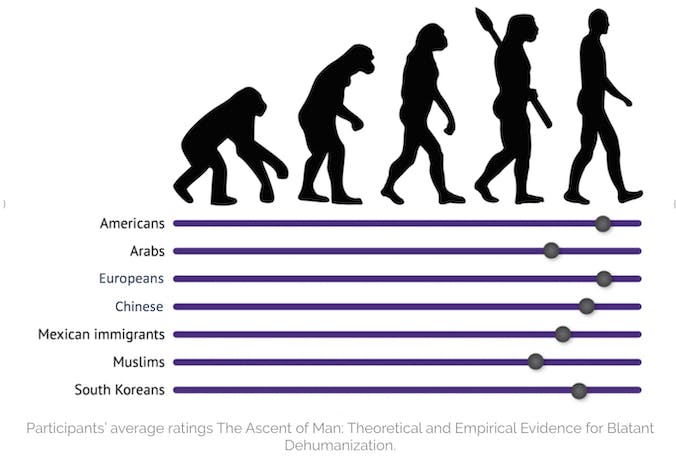

In a study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in 2015, 201 ordinary Americans, 75% of them White and most of them male, were given this prompt:

“People can vary in how human-like they seem. Some people seem highly evolved, whereas others seem no different than lower animals. Using the image below as a guide, indicate using the sliders how evolved you consider the average member of each group to be.”

Yikes.

In the considered, collective view of the study participants, Muslims, Arabs, and Mexican immigrants are clearly less “human-like” than Americans and Europeans (Swiss, French, Austrians), while South Koreans and the Chinese occupy an evolutionary middle ground. My guess is that in the United States of 2017 Muslims, Arabs, and Mexican immigrants would fare even worse.

Dehumanization isn’t just perceptual fluff. Participants who saw an evolutionary gap between Muslim Americans and themselves preferred funding greater surveillance and more policing over more schools and libraries in those communities. The belief that target groups were subhuman also predicted less concern about African American and Arab victims of injustice, less support for Hispanic immigration, lower donations to a Chinese charity, and more.

In the conveniently, insistently hyper-privatized middle space of interpersonal attraction and dating, can dehumanization show up as racial friendzoning, aka sexual racism? Of course.

What self-respecting person would want to date a subhuman?

Connecting Dots

I’m hardly the only person to have gone through high school feeling invisible in one way or another, or to have done so for reasons linked to “difference.” Moreover, we’ve become more open to interracial dating in the United States over the three decades since my high school days and cross-racial marriages are now relatively common. Is racial friendzoning even a thing nowadays?

Yes, it is.

In 2014, the online dating site OkCupid looked at the “basics of race and attraction” among its men seeking women and women seeking men. (Much less work has been done on cross-racial attraction and aversion in the gay community.) Here’s what they found.

- All groups of women were most likely to respond to inquiries from same-race men. Men had weaker same-race preferences, but only Black men showed no same-race preference at all.

- Asian American, Latino, and White men all friendzoned Black women relative to other women.

- Black, Latina, and White women all friendzoned Asian American men relative to other men.

- Latina and especially Asian American women friendzoned Black men.

Of course, the fact that other-race women prefer white men to Black and Asian men doesn’t tell us how many women rule out Black or Asian partners as definitively as high-school-Bob ruled out Black girls, much less why they do when they do.

Yet the consistency of the findings tells us something. Among straight people, African Americans, especially women, are effectively friendzoned much more than their peers are. (Is it coincidental that many Americans subconsciously associate Black people with apes?) Asian American men don’t fare well either. And, yes, “Black women and Asian men are far less likely to marry interracially or inter-ethnically than Black men or Asian women.”

Racial friendzoning is very much a thing.

In Sum

In high school I felt dehumanized. Later, like the peasant in Monty Python and the Holy Grail who had been turned into a newt, I got better. But it took a lot of love and friendship to convince me that I wasn’t a newt. All the people complicit in my dehumanization were ordinary people — peers mostly, but also teachers, friends’ parents, coaches — not avowed racists or Neo-Nazis. So, too, were the people who helped restore my full humanity to me.

My story is a common one. Variations on it unfold all the time — in our schools, colleges, and universities; our workplaces and vacation spots; our community centers, chatrooms, and parks; our churches, synagogues, and mosques; via radio, television, movies, and news media — wherever we encounter each other and consider ourselves through the eyes of others.

When the people in your life, and at the margins of your life, look into your eyes, what of themselves do they see reflected there?

Andrew Grant-Thomas