Epiphanies On Race

By Anonymous

On June 30th, EmbraceRace posted an article by a gay black man entitled “Why I’m Giving Up on ‘Allies’.” The author, Ernest Allen, writes this: “What I have realized is that too many allies conduct themselves as service providers: They show up only when there’s an immediate need, they require me to explain the problem again and again, and they may or may not actually fix anything. In other words, allies are more trouble than they’re worth.”

This piece, submitted anonymously, was prompted by Allen’s reflections.I'm white and I grew up in mostly white places.

I'm white and I grew up in mostly white places.

Before high school, I knew only two black people. I loved both of them. Our family moved when I was in ninth grade, so I went to a mostly black high school in a poor neighborhood, but, even there, students in the honors classes were more white and Asian. I went from there to college, where there was, for the most part, de facto segregation of the student body, and then moved on from there into a career where nearly everyone I worked with was white, outside of some staff and administrators.

During that whole time, I gravitated towards people of color. Dunno why. Despite that, it took me literally until I was pushing 50 to understand what white privilege is, why reparations remain a real issue, why black students might want their own graduation, why “safe spaces” is a thing, why reverse discrimination isn’t, what fetishization is, what cultural appropriation is, why empathy and appreciation are not equivalent to shared experience, etc.

I mean, my whole life I should have been an ideal “ally” in terms of intent and heart and willingness to learn and STILL it took me until 50 to even begin to understand.

I think this was because, to really see, I really needed an epiphany. No matter how much I embraced and loved and respected and appreciated individual people of color and no matter how utterly and genuinely open I was to equality and fairness, I just didn’t get it until I got it. And I only got it when a black friend took a walk with me one day and explained to me why, in college, a separate graduation ceremony was important to her.

I had come to the conversation convinced that such self-segregation was counterproductive and verging on racist. But, with incredible patience, she explained the relief of being among other black people who shared her experience, had also lived the challenges of being a minority, and, in enveloping her, gave her a reprieve from the exhausting, endless, day-to-day of being noticeably “other.”

She made me understand the relief of escaping, if only for the duration of a brief ceremony, the grinding frustration of trying to work within a system not designed for her, where even the best-intended white people made assumptions about her abilities and interests and character on the basis of her color.

What I took for granted — living in a world where I wasn’t judged for, or structurally restricted by, my color — was something she did not have. Ultimately, I needed to understand that the separate ceremony was not a rejection of white people or a stinging rebuke. In fact, it was not about white people at all. It was a family reunion, a warm embrace, a coming home.

Somehow, finally, that little bit of true understanding then set off an avalanche of eye-clearing, mind-opening recognition, sweeping away false conceptions.

I had to re-think comfortable assumptions: that it is better to be colorblind; that prejudice = reverse racism; that self-segregation by people of color is inherently hypocritical; that progress is better made by adhering to social norms; that the problem lies not in race, but in class.

As embarrassing as it is for me to acknowledge, those are all familiar ideas to me — I’ve thought them all at one time or another as I worked through issues of race. In fact, those ideas were part of my rejection of racism. Because of that, I can understand how other white people embrace each of those ideas, even white people who see themselves as allies and are genuinely appalled by racism.

It’s a question of the view from where you sit. Unless you have that epiphany that shifts your perspective and lets you see beyond what you’ve always seen, you may not get it. And even then, it’s work. Long after this eye-opening conversation, my first thought when I heard #Black Lives Matter was All Lives Matter. Not because I rejected black lives but precisely because I thought they should be seen as equivalent to all other lives. To appreciate and support BLM, I had to learn where it was coming from, think about it, clue in. I also had to know to do that.

Ultimately, the most insidious aspect of white privilege is not seeing. Our experiences of the world work against us truly seeing how others experience it.

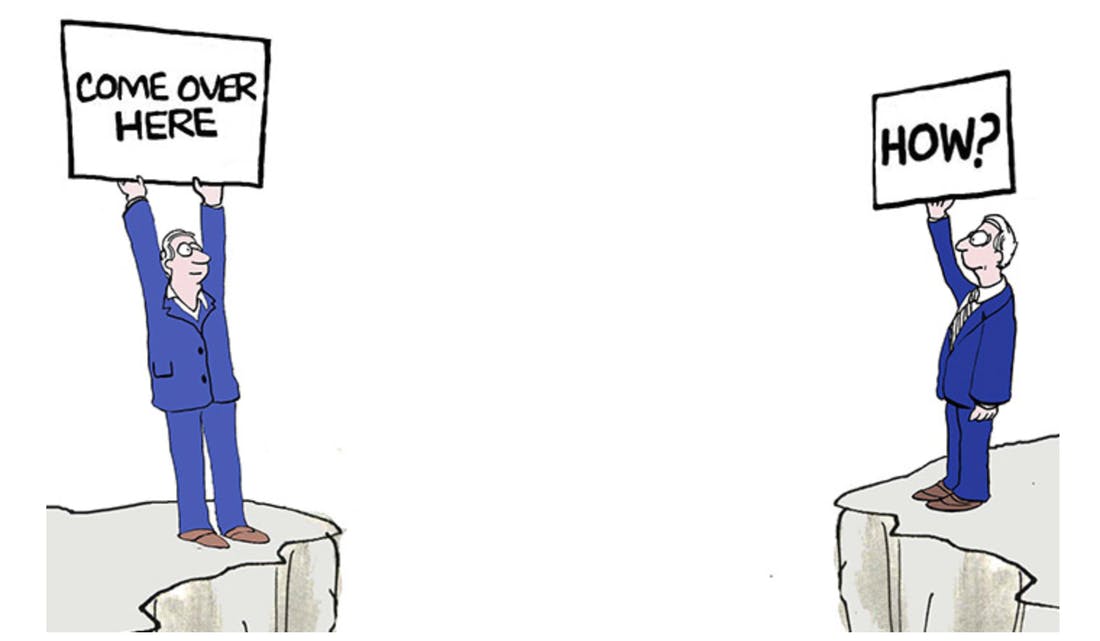

I don’t know how to fix that without putting a tremendous onus on people of color to do the tiring, defeating work of constantly explaining, on the chance that some proportion of the people they talk with will have that epiphany.

I don’t know how to fix it when it requires a fundamental shift in perspective that has to be jarred loose, since perspective is so unconscious.

I don’t know how to fix it when the language itself works against mutual understanding and when the process of fixing it automatically raises defensive hackles even among the committed.

But, grateful for the conversation my friend had with me, I’ll have those conversations with others. Like this.