"Does That Happen to You?"

Racial Profiling and white privilege in my all-American multi-racial family.

By Gita Gulati-Partee

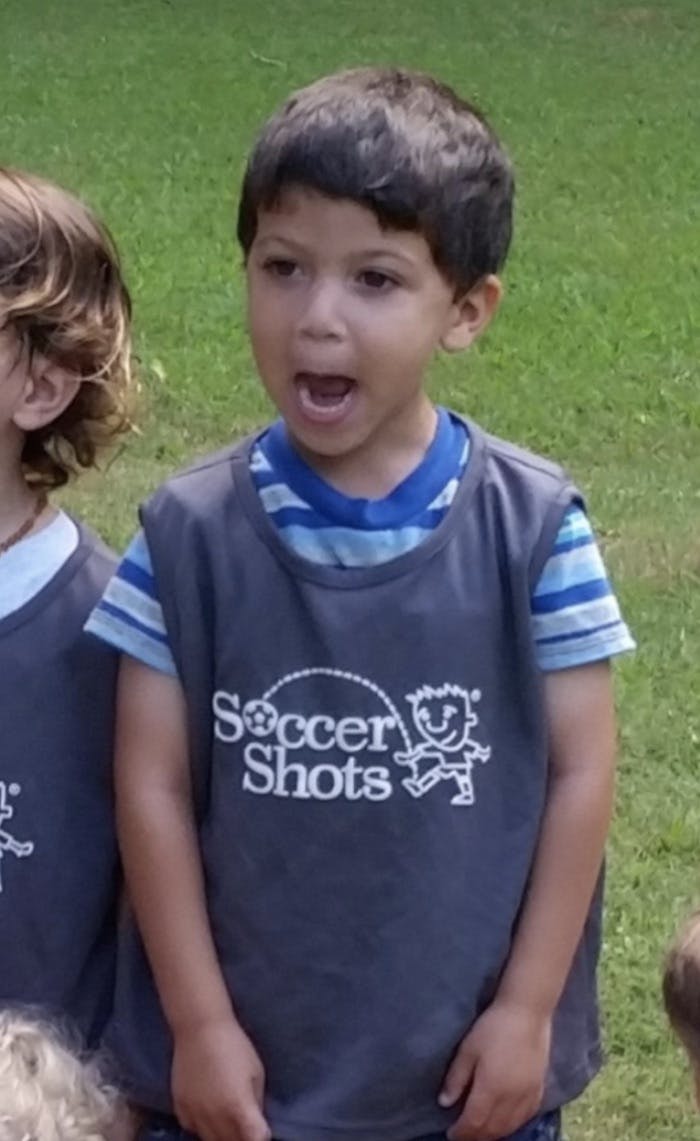

We meet my parents every Sunday, either for brunch at their retirement community or dinner at our house. We usually focus on Krishna and his latest antics. From the positives, like beginning to learn soccer and swimming, to the not-so-positive, like making himself burp — loudly, and often. We are political animals, and we often discuss current events, especially in an election season.

We talk freely about race and racism, which they experience acutely in their overwhelmingly white community in some of the same ways as when they first immigrated to this country from India over 50 years ago. Maybe it’s true about any generationally specific space, it seems kind of trapped in time. My parents are not shy, and having a multi-racial family definitely provides lots of material for us. I remember the moment I knew they were comfortable with Edd joining our family, and that Edd could hold his own and fit right in. It was before we were married, but we had been together for a while and were visiting them at their house for lunch.

My mother said, “Edd, I want to ask you something…” — five words that always made me hold my breath — “What is this joke about black people and watermelon?”

I cringed, and started to jump in to try to turn (i.e., save) the conversation. But she beat me to it, and charmed us to boot. “Does not everyone love watermelon?” she inquired. “Who could not love watermelon — it’s so juicy!”

Edd, who is as earnest as mom is curious, leaned in, “It is juicy, mom. I don’t know who doesn’t love it.” Then, they shared an eye roll and shrugged their shoulders in joint incredulity — “white people,” they seemed to sigh in unison.

“It’s so juicy!” has been the ultimate compliment in our household ever since.

But despite all the ground we’d covered over the decades that Edd and I have been together, my parents had never before asked this particular question: “Does that happen to you?”

Like everyone, we were talking about the recent spate of televised acts of violence against black and brown men at the hands of police. The phenomenon is not recent at all, but rather the continuation of a generations-long reality. But being captured on video and broadcast 24/7 makes it feel both new and urgent to a lot of Americans, my parents included. For the first time, they were really absorbing the idea of “racial profiling” and “driving while black.”

So on this occasion together they said they have been hearing about the problems that black people experience with police, and they asked Edd, “Does that happen to you?” Edd answered with trademark understatement: “Sure.”

When they pressed him for more information, he told them of a couple of times when he might have been driving a little fast, but was right in the flow of traffic and it seemed odd that he was the one driver pulled over. And there were other times where there was literally no reason — none that Edd could think of and none provided by the cop. We chose not to share more harrowing tales of being targeted by racial bias and unfettered white privilege (more in future posts), just the routine stuff that happens everyday.

They were saddened by Edd’s experience, and could only shake their heads in silent solidarity. It was hard for them to imagine this happening in this country; even more, to imagine it happening to their beloved son-in-law. The man who is so helpful and supportive to them, while I am often too busy and self-absorbed. The one who patiently answers all their technology questions, even the basic ones they’ve asked a million times before. The one who eats every bite of my mom’s cooking and inquires into her culinary tricks and techniques.

No wonder I call Edd the “Indian daughter my parents always wanted.”

White privilege for people of color?

In my last posting, I wrote about our experience, as two parents of color, adopting and raising a mixed-race son who is, by heritage and by pigment, whiteish.

Some readers commented that, though our situation is relatively unusual and comes with unique challenges, aren’t we lucky because Krishna will avoid some of the hardest hardships facing dark-skinned kids of colors. That he, in fact, will enjoy white privilege.

I understand that each of us has some privilege, unearned, granted solely because of some aspect of our identity, real or perceived. And I understand that, within groups of color, lighter skin is privileged.

I can imagine Krishna having some whiteish privilege — though we are still figuring out how to define that.

But white privilege feels like a stretch for a kid of color, no matter how light skinned.

Is Krishna likely to be the one among a pack of drivers going just a little fast to be pulled over? Is he at risk for mistreatment or violence at the hands of police officers or other authority figures? Is he bound to be denied opportunities because of explicit or implicit racial bias? Or rather, might he be presumed white and benefit from the presumption?

It is hard to say. Though whiteish, it’s hard to imagine anyone reading our light-brown son as white. And being located in our family of color would make that even less likely. Rather, it might open him up to questions that are familiar to me as someone who grew up brown and ethnically ambiguous in a black-white context: “What are you? Where are you from?” White privilege would inoculate against such vetting.

More importantly, any advantage Krishna might get is arbitrary at best, dependent upon the whim of the white gaze — the way that white people see people of color and, more importantly, have the power to define the worth, normality, and very reality of what they see — and whatever it determines is in the best interest of white supremacy in a particular moment. Throughout history, we have seen different categories of people pulled in (Irish, Italian) and pushed out (Arab) of whiteness for the purpose of preserving its power.

So any racial privilege that Krishna might have is inconsistent and unreliable at best. And still, this seems like a narrow way to understand either race or privilege. It suggests that it manifests only in the form of individual bias, from which we parents just need to protect our child by keeping him away from obvious bigots. (Note to self: avoid obvious bigots. Also obvious pedophiles, serial killers, and drunk drivers).

But that obscures the larger, more subtle ways that white supremacy is baked into every aspect of our lives.

I imagine all sorts of ways Krishna, like countless kids of color, could suffer the consequences of racism. From a health care system designed around white male physiology and norms — which means that his particular health needs might be overlooked or mis-diagnosed or mis-treated. To less generational wealth than our white counterparts even when we are in the same income bracket — which means he doesn’t have a safety net to rely on or leverage to manifest the American Dream. To not seeing himself reflected in images of agency, leadership, and beauty in his textbooks or our popular culture — which means he might not really believe he can be and do anything he wants, despite our drumbeat of encouragement.

I also imagine some unique ways Krishna might encounter racism — like the very real possibility that someone, perhaps an armed police officer, might decide that he and his dad couldn’t possibly fit together, and act in ways that are damaging to our family physically and/or psychically.

To be sure, all parents worry about their kids, and do their best to raise them to be safe and actualized. But parents of kids of color, even if they are relatively light skinned kids of color, cannot rely solely on how our kids are raised; that depends also — more — on how they are raced. That is what keeps us up at night and anxious throughout the day.

Does that happen to you?

Gita Gulati-Partee

Get Insights In your Inbox

Join our community and receive updates about our latest offerings - resources, events, learning groups, and news about all matters race and kids in the US.

Subscribe