Dear Brown Girl: Proximity-To-Whiteness Does Not Make You White

by Divya Kumar

As a child of Indian immigrants growing up in white suburban Connecticut, I was the only brown kid in school for most of my early childhood. Constant race-based microaggressions and straight-up bullying in elementary school taught me that my Indian identity brought ridicule and shame at the hands of my white peers. No one could pronounce my name, and both kids and teachers found humor in butchering it. We had statues of Hindu deities in our home, I knew no Bible stories, and I had never been skiing. Our kitchen at home “smelled weird”. Some of my friends’ mothers remarked that they had never had an Indian kid at their house.

My mother had this funny habit of always pointing out every other Indian-appearing child in any public place - “Look! There’s another Indian girl! Go and say hello to her; maybe you’ll make friends?” When I was a young child, I found it perplexing and didn’t understand why I would have anything in common with a random girl across the room. I would reply to my mother, “Just because she’s Indian doesn’t mean that we actually have anything in common!”

By middle school, after years of being laughed at for being different, I knew that in order to survive socially, I needed to move as far as possible from anything Indian, so I chose to assimilate and render myself as culturally white as possible. I listened to Phish and wore tie-dye shirts and Birkenstocks. I told my peers that I didn’t like Indian food and that we celebrated Christmas “just like everyone else.” I wanted no part of the Indian community my parents were peripherally involved in and looked the other way when I saw Indian kids in public.

Seeking Social Safety: Crafting an identity as a reaction to racism and fear

Through adolescence, I built social armor consisting of Grateful Dead and R.E.M. CDs, white friends in flannel shirts, and white boyfriends with long hair. By the time I got to college, I felt far away from the child who was ridiculed for being different and wanted it to stay that way. I saw posters advertising Desi student groups and saw no connection to those groups or a reason to participate in them. I continued to distance myself from my ethnicity and everything my parents wanted me to be and no longer faced the overt race-based bullying I did when I was growing up.

Of course, racism is endemic, inevitable, and etched into so many cultural cornerstones and daily interactions. While I no longer experienced overt racism from my peers, I experienced microaggressions constantly; for example, the person taking tickets at the movie or seating folks at the diner nearly always assumed that I wasn’t “with” my group of white friends.

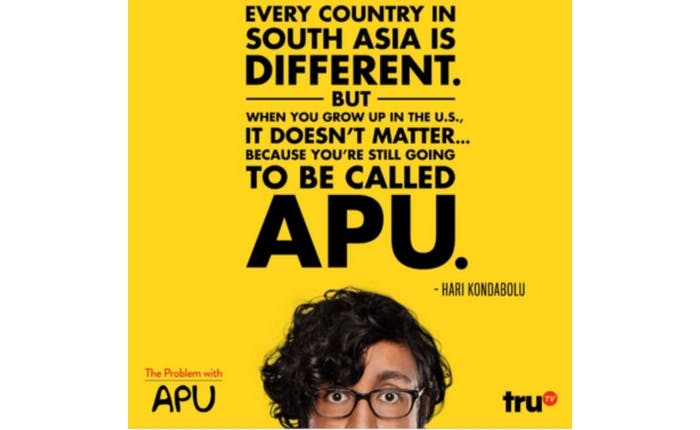

Also, the effects of years of daily race-based bullying were forever etched into my autonomic nervous system. I remember watching The Simpsons with a room full of friends in college and cringing as the room erupted in laughter at “thank you; come again!” In that room surrounded by friends, I felt a nagging sense of dread and discomfort that I couldn’t quite identify, but I knew it was related to my cumulative experiences of growing up brown among white folks. I felt uneasy, unsafe, and reminded that I didn’t fully belong; moreover, I was reminded that to truly belong, I would have to swallow that reaction to Apu and let it go. Calling it out was never an option.

For periods of my life, pushing down that nagging, nebulous discomfort seemed to work. I married a white man that I loved and started a family; I made white friends who I felt accepted me for who I am and with whom I felt safe, and I moved into a community that, on the surface, felt both diverse and welcoming of diversity.

The 2016 Election validates years of racial trauma

After the election in 2016, when this country elected a president who had run on a platform of racism and hatred, I felt raw and vulnerable in a way that I hadn’t felt in years. Even though I lived in a progressive neighborhood and was surrounded by friends who were white allies, all of the memories of all the horrible things people said to me when I was a kid came back to me in a flood that I couldn’t stop. The body remembers, and it remembers vividly and viscerally, even after years (decades) have passed. That discomfort and feeling of always being on alert that had been firmly carved into my neural pathways returned with a vengeance, and I found myself on guard when I walked down the street in my liberal bubble of a neighborhood. I felt no longer able to push down and swallow the hurt and, moreover, I finally saw my proximity-to-whiteness strategy for what it was: a response to racial trauma.

During those post-election months, I found myself seeking out folks of color in an unprecedented way and craved spaces without white folks. I wanted to be around people who understood my sense of not feeling safe, people whose neural pathways were activated by the same triggers and who would understand a history that carried pain and shame that I didn’t want to have to explain. I wanted to be around people who were also seething with rage and biting their tongues to keep from yelling at white women in yoga tank tops with our zip code shaped into a Sanskrit Om on their chests. I wanted to be around people who also felt the knee-buckling ire at seeing grown-up versions of the kids who teased us for being brown now eager to commodify, consume, and appropriate our culture with the latest yoga trend. I wanted to be in spaces where I didn’t feel hypervigilant, where that sense of uneasiness could abate a little. When I did find those spaces and made those connections, I felt like was exhaling after years of holding my breath.

Back in college, while no one pointed at me and said “thank you; come again”, neither did anyone name the racism that was central to Apu’s character. Both then and now, while white folks around me both could and continue to ignore racism because it doesn’t affect them directly, I am and have been continuously left wondering for all of these years if I am crazy or over-reacting whenever I have that visceral reaction to racism. Racist internet memes such as those making plays on “Namaste” fill me with self-doubt to this day. If (white) people close to me don’t see the racism in that, am I imagining it? Or am I being too sensitive? The rational side of me knows that I’m not, but after years without acknowledgment or validation of my reactions, the feeling of doubt is ingrained.

Perhaps this is has been the hardest piece of being surrounded by whiteness and flirting with the feeing of safety: just when I think that I have reached a new level of comfort, I am blind-sided by racism and then blind-sided again by the gaslighting of white peers. I’m told the comments on a parenting listserv were “well-intentioned”, and I was being “too sensitive” because someone was “pushing a hot button” for me. I’m assured that a so-called content expert’s racist remark about an Indian physician in a course I took was just “the speaker’s perspective”. When the white people around me have chosen to not acknowledge racism and have dismissed my perception of racism, I doubt myself, and I stop speaking up. I am faced with the choice of staying quiet and swallowing that repeated experience of oppression or speaking up and risking angering and alienating my white peers. Neither choice is fair or appealing, and I find myself spending a great deal of energy making mental calculations about the pros and cons of speaking up vs. staying quiet.

Moving forward: Parenting my biracial brown children

As a parent of two brown kids who are on the verge of adolescence, I often wonder what advice will resonate with my kids and think back on how my own mother used to always tell me to go talk to whatever Indian girl she saw across the room, as if being Indian was enough to make us friends. What did my mom think I would gain out of those interactions? Did she think we would talk about the music or TV shows we liked? Or did she think we would see a mirror of our own racialized experience in a peer—that we would talk about the ways our names were mispronounced and how white girls held their noses in our mothers’ kitchens? Did she think we would talk about the uneasiness we couldn’t quite name but that gnawed at us nonetheless?

Thankfully, my kids do not face the overt racism that I faced as a child. That said, I feel an obligation to warn them about the illusion of proximity-to-whiteness as protection from racism, and to encourage them to make different choices than I did. In our ongoing and future conversations and by example, the gist of what I want to communicate with them about resisting racial oppression is this:

“Make sure you have close friends of color. Racist stuff will happen to you, and you will not want to face it alone. Your white friends will be able to choose whether to see racism and see your pain, and that will hurt. Your friends of color will be more likely to validate your experiences with racism because they, too, have experienced racism. You will need those people around you so that you don’t doubt yourself and your own truth. Also, people of color are situated differently from each other, depending on their racial identities and all of the different ways that people can be oppressed. You will need to be a good ally by seeking out and showing up for friends and peers of color whose experience of racism is not like yours and is worse than yours.”

I have love and compassion for the kid I was, who at my kids’ age, had learned to craft a self and an identity based on fear and a desire to survive socially. I wish someone had understood and validated both my fear and my desire to emulate whiteness—and I also wish that I had had the social safety of other options besides blending in or being an outcast. And I wish I had had an understanding of how my own privilege (in the form of access to white spaces) granted me these options while denying them to other folks of color. As I reflect on the layers of what I did not understand as a child and adolescent, I hope that I can offer guidance to my kids so that they can name and navigate the many nuanced layers of oppression and privilege.

What if I had gone over and talked to those Indian girls across the room years ago? Would we be best friends now? Probably not, but we might have connected over our shared experiences. I might have been able to make different choices as brown girl creating space for herself in a white-centered culture if I hadn’t faced racism alone. It took me years to find spaces where I could exhale and speak my truths about racism freely, and I want my kids to grow up with those spaces built into their social scaffolding as early as possible. I want my kids to have peers who are also navigating the world as kids of color, who can provide that space to exhale, and who can say, “Yeah, I get it.”

Divya Kumar