Can We Raise Inclusive Kids in Segregated Neighborhoods?

Many parents want their children to embrace racial diversity and multiculturalism. Research shows that people who grow up in diverse neighborhoods and attend diverse schools express less racial prejudice and are more supportive of multiculturalism. However, neighborhood segregation means that many U.S. families live in racially homogenous neighborhoods and many children go to school mostly with same-race kids. In this session we discuss the importance of being color-conscious (rather than "not seeing color") and offer some ideas about how to foster inclusive attitudes in children - of all colors - who live and attend school in these homogenous environments.

In this hour-long conversation, first, Professor Vittrup presented what she’s learned and discussed the implications for raising kids. Next, EmbraceRace Co-founders, Andrew Grant-Thomas and Melissa Giraud, facilitated the Q & A with the community. Watch the video and find the tipsheet (linked above), read the transcript (below).

EmbraceRace: Brigitte Vittrup is an associate professor of child development at Texas Women's University where she teaches courses in child development, research methods, and statistics. She holds a PhD in children's developmental psychology from the University of Texas at Austin and her research focuses on children's racial attitudes, parents’ racial socialization practices, and media influences on children. Bridget identifies as white.

I will turn it over to you, Brigitte. Brigitte will present for 20 minutes or so and then we'll turn it over to questions.

Professor Vittrup: Thank you for inviting me.

Professor Vittrup: I did need a picture of my family on the front page just so you know some context also for who I am and who my family is. This is a topic that's very relevant to me and has been for a long time. I want to start by talking about what inspires cultural competence and awareness in children. So certainly experience. When children have positive interactions with people who are racially and culturally different from them then that does have a positive impact on them. And then also diverse surroundings because what we do find is that children that grow up in diverse neighborhoods and attend diverse schools express less racial prejudice and also seem to be more culturally sensitive. Experience is important.

Professor Vittrup: But obviously, we're doing this particular presentation because there are a lot of people around the United States who live in very homogeneous neighborhoods and because of the way that the school system works then that means that the schools are somewhat homogeneous as well. But there is also education. And parents are big educators in their children's lives. Teachers and child care workers as well. And then various educational resources. And so I will be talking about that and some of the opportunities that we have as parents and as teachers, educators for our children.

Professor Vittrup: If we look at the reality, U.S. neighborhoods are very segregated. People who study this use something called the dissimilarity index and it's looking at how dissimilar are people in the neighborhood essentially how much diversity there is or is missing. And so zero would be perfect integration.

And what we find is that in large metropolitan areas, dissimilarity index is about 50 to 70 and especially find that blacks and Hispanics tend to be hyper-segregated in these areas. And so just to show you what it looks like, here's a map of New York City. So you can clearly see its color coded. The blue dots represent where black people live. Orange is Hispanic. Red is Asian. Green is white. And so we can already see the clusters that are appearing there.

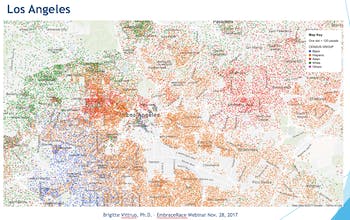

Professor Vittrup: Another example is from Los Angeles where people tend to be more spread out but it's still somewhat segregated.

Professor Vittrup: And then one example that really shows it is Detroit where the middle line is Eight Mile Road. And you see that we have stark segregation between black and white here. And then little bitty Asian community and a little bubble down towards the end.

Professor Vittrup: So certain areas are more or less segregated but overall in the United States we find segregation and some measures are showing that actually both schools and neighborhoods are more segregated now than they were in the 60s and 70s. So we haven't really moved towards more integration which is certainly what was the hope after Brown v. Board of Education.

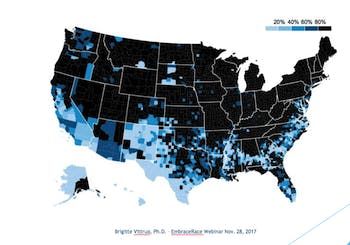

Professor Vittrup: Schools are also pretty segregated. Sixty percent of black and Hispanic children attend schools that have 75 percent or more of minority enrollment, whereas only 5 percent of white children attend schools that have very much diversity to have any kind of minority involvement. Here is a map that shows this as a share of the percentage of black children that are attending majority non white schools. So these are the schools where the majority of the enrollment are minority students. And certainly across the south and up on the east and west coast, we see very high concentration of segregated schools.

Percentage of of Black children attending majority-nonwhite schools

Professor Vittrup: This map shows the share of white students attend majority white schools. And certainly across the whole North and Midwest many of these schools are just majority white schools.

Percentage of White children attending majority-white schools

Professor Vittrup: So what happens is that that gives children limited opportunities for interactions with people who look different from them - people who are racially and culturally different. And also the information that they do get about other groups of people, other families different from their own, is second-hand. And it's often either incorrect or incomplete or distorted. You see a lot of stereotypes represented for example in the media which oftentimes is a major source for these children that live in very homogeneous environments.

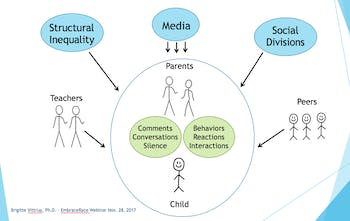

If we look at what influences children's beliefs about others and about the world certainly parents and other family members, teachers and child care workers, these are socializing agents in the children's lives.

But as children get older and they spend more time away from their families, they start to become more influenced by their peers as well. Certainly, kids are heavily involved with media. But one thing I'm gonna talk about, too, in this presentation is just other people's behaviors, their comments, their reactions to things are going to have an influence in combination with just how visible social division and structural inequality is in this country.

Professor Vittrup: We have the structural inequality that's in place, we have the social divisions. These are some things that we as parents can't immediately do anything about. Media to a certain extent when children are young we can regulate that but certainly not as much when they get older, and children have a lot of private access to media, iPads, smart phones, TVs in their rooms. Even though we can restrict and mediate some of that, there's still a lot of influence that we can't prevent. And so then you see also teachers and peers are starting to have this influence.

And what I put in the circle in the middle is this buffer zone. This is the opportunity for parents to serve as buffers for these external influences on children. Influences regarding inequality and various messages about race and race relations in this country. And the two bubbles in the middle that contain essentially the words and actions of the parents. Comments that they make - positive or negative - that influence the child. Direct conversations that they may or may not have, any kind of silence about the issues, and then also the actions, the behaviors, the reactions and the interactions that they themselves are engaged in. And so depending on how strong these are and how much involvement, how much the parents are talking, how much they are doing, is going to influence how strong this buffer zone is to these external influences.

Professor Vittrup: If we look at some of the messages that children hear and see on a regular basis, with today's 24/7 news coverage, it is hard to completely shield children, even young children, from some of the media messages. And so they see black men being taken down by white police officers. They see white nationalists protesting. They see signs about, you know, "Make America White again." And so they having to try to figure out what all of this means. And then meanwhile they see the white principal and the black and Hispanic service workers. So over time, especially when there are no counter examples or not a lot of counter examples, and if there are not a lot of conversations going on, this essentially colors children's viewpoints of what the world looks like and what the world should look like.

Part of my research has been looking at how do we intercept some of these messages? What can parents do, and what are parents doing? So it's important to have intentional conversations where we're not just waiting until children ask us questions or make comments that we actually make an effort and plan to have conversations about these issues with children. The conversations look a little bit different. Whether or not you are an all white family or an all black family, or an all hispanic or asian family, or if you are an interracial family. But no matter what your family looks like, these conversations are important. And then also exposing children to counterexamples. And I do have some suggestions on how to do that.

Professor Vittrup: If we look at reality and what parents are actually doing, usually parents say nothing. Some parents say more than others. But what I really found in my research, and this is both research with with parents and teachers, is that they are quite uncomfortable about it. Silence about race and about race-related matters is very common, especially among white people, but in many families of color as well.

I've asked a lot of parents whether they talk about race, what they talk about and, if they don't, why do they choose not to. And over and over again, the messages that I'm getting is that they want children to grow up and be "colorblind." This ideology of colorblindness has been around in the United States for quite a while. For decades, that has been what many consider the right thing to do. Let's just not see race and let's treat everybody the same. It's well-intended. Many parents decide not to talk about race because they don't want children to notice what they think they haven't noticed already. They really think their kids are "colorblind." Almost all parents that I have surveyed believe their children have either no biases at all or barely any biases. In fact, the research on children's racial attitudes shows us that children show a fair amount of bias.

Many have also expressed that they're uncomfortable with the topic. I just don't know what to say. I'm afraid I'm gonna say the wrong thing and then I'll get in trouble. And so these are really the major reasons why we're finding that so many adults don't talk about race and race related matters. The problem with this colorblind approach is that, first of all society is not colorblind. We see these social divisions based on race. We see the structural inequalities and these are obvious to children as well. And we have issues with prejudice and discrimination that's certainly no secret. And children are not colorblind as much as we might think that they are because they might not be saying a lot. Research does show that children as young as preschool are forming ideas about race and cultural differences even before they have the labels for it. But they are starting to make judgments already that early.

Professor Vittrup: Children are noticing even if we think they're not. And then "colorblindness" really does nothing to move us forward towards more equality and integration. Instead, it preserves the status quo. If we say we're not going to talk about race and will just treat everybody the same, we're fooling ourselves. In reality, we're not treating everyone the same if we're not fighting to erase some of these issues of inequality.

And really most importantly, silence is a message. Silence sends a huge message to children. When children ask questions or make a comment and they're told, "no don't say that" or "we shouldn't be talking about that," it sends the message that either these people who look different from us, we shouldn't talk about them, they are not important. Kids wonder, maybe there's something wrong with these people because they don't see their parents really interacting with a lot of people that look different. They look around their neighborhoods and their schools. They see that most people look the same and nobody's talking. And so it must be because we shouldn't be interacting with these people.

Professor Vittrup: They also pick up quite early on that this is a taboo or dangerous topic and stop asking questions. So when parents are thinking: "Well, my child never mentions anything. Certainly we'll talk about it if he brings it up!" But most likely he's not going to bring it up because he has already internalized that this is something we don't really talk about. Unfortunately, it can send a message that, well, inequality is just the way it is, these social divisions, that's just how it is. Some people just deserve more than others. And that's certainly not the intended message but oftentimes is the message that it ends up sending.

Professor Vittrup: It's really important also to note the fact that when we are silent about race and race related issues we are trivializing the voices of marginalized people and it can lead minority children to feel devalued and feel that they don't have a voice, because, again, nobody is talking about it.

And then another consequence. What I have found in some of my research is that children are not very good at predicting their parents' racial attitudes. The parents often assume that, "Well, I'm unbiased," (which in reality, none of us are unbiased, we're all products of our environments). But they feel [about themselves], "Well, I treat everybody the same. I interact with people the same. I don't discriminate against people. Certainly my children will pick up on that." However children often don't see their parents interacting with others that look different. And there's no conversation about it.

Professor Vittrup: So what we find is that there's a very low correlation between children's and parents' racial attitudes. But there is a very high correlation between children's racial attitudes and their perceptions of their parents attitudes. And the reason is, they don't see their parents interact with people that are different. Even when parents are saying, "I have friends that are of a different race." Often times they are referring to colleagues or people that they might have gone to school with and they don't live nearby anymore and so children really don't see them interacting very much.

Another reason is that then when parents don't talk about it, again, the children are having to figure it out on their own. And so they often think that their parents are a lot more biased than their parents are. And often to the dismay of parents. And then that influences the children's attitudes, what they think they're parents are thinking. So the question is, what can we do about this?

I showed you a graph earlier that showed that parents really do have the opportunity to serve as buffers. And so first of all, we can have conversations. And essentially what I usually tell people and tell parents just say something, don't say nothing. And you won't always get it right and that's OK. Because as you have more conversations you'll get more comfortable with it. And I have suggestions for conversation starters. You can really use books, videos, news stories as springboards for conversation, because you will have a starting point for something to talk about.

Professor Vittrup: As far as books, find books that include topics of diversity. There are a lot of books out there. The EmbraceRace website has links to good books that include diversity.

What's important is to engage the child in conversations because even the books that have messages of diversity and have diverse character, oftentimes they're not quite as explicit as we need them to be in order for children to really pick up the messages.

So ask the children about the characters in the book, about the experiences of the characters, you can imagine the child part of the story, being friends with one of the kids.

And don't be so afraid to mention race. Especially if you're talking about the characters and noticing that they look different, and they're friends and isn't that great. And you know, what would you say to this friend that looked different than you and what would you have in common? Then talk about things like fairness and inequality and bias. You can ask the child, what do you think? What would you think if this happens? What would you do? And certainly the conversations differ based on whether or not you're talking to a 4-year-old or a 14-year-old because they have different things that they can understand and also you can read more complex stories with the older kids.

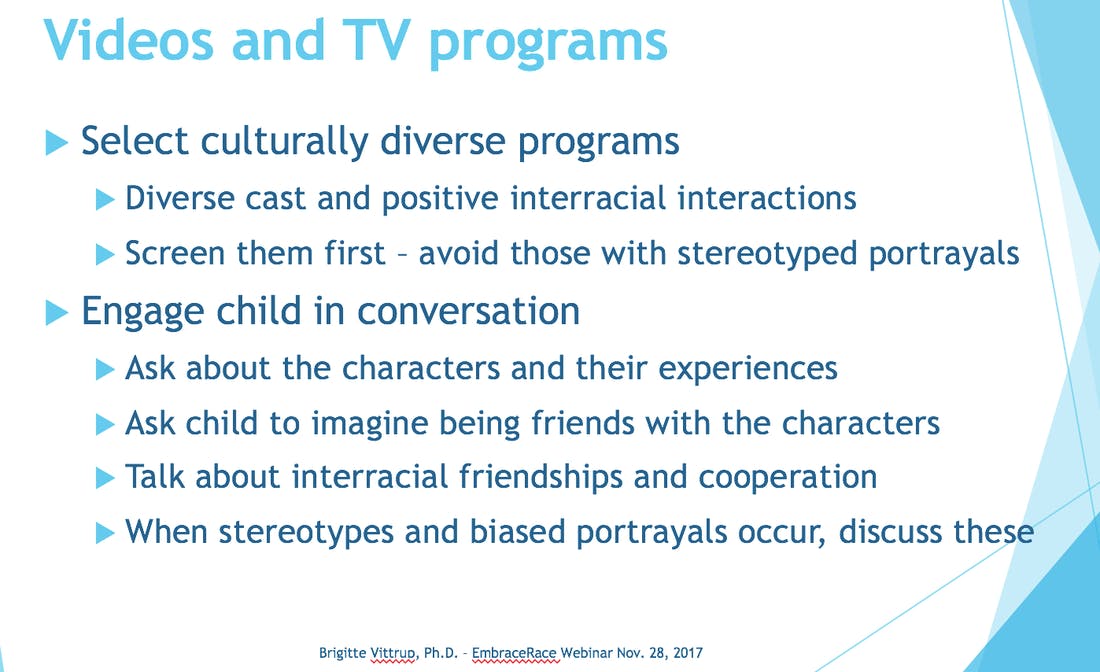

Professor Vittrup: Another suggestion is for videos, movies, TV programs. It's important to select those that are culturally diverse so look for those that have a diverse cast that are showing positive interracial interactions. And for TV programs can be difficult at times. Children's TV is a lot more diverse than adult programming but we're still seeing it still barely 30 percent of children's TV is considered truly diverse. Certainly screen these videos or movies first just to avoid the ones that show a lot of stereotypes. Ask children about the characters, about the experiences. Ask them to imagine being friends with the characters and have conversations about what happens, about interracial friendships and cooperation.

Professor Vittrup: And if there are stereotypes and biased portrayals that occur, because it happens even in diverse programming, be sure to discuss those, to bring it up and say, "They're portraying these people in a certain way. It is a stereotype that doesn't mean that everybody is like that." And over time, that will also help the children build media literacy skills to where they can start picking up on some of those things.

Professor Vittrup: And then news stories. There are plenty to pick from. This tends to be better for older children because there is, obviously, content that younger children are less able to really understand or that can make them scared.

You can watch the news together, and you can select the stories you want to talk about, and then really engage the child in conversation about the content - about what is right, what is wrong, even about the way that the story was told the way that people were portrayed in these stories.

Because oftentimes in news stories there's a certain slant to it. And then you can ask the child why do you think this is happening? Why did this happen? What would you do? What do you think about this? And these are ways that you can really start using these as a springboard for conversations.

Professor Vittrup: So the first thing to do, with prompts from books, videos, life, is to have these conversations.

The second part is, try to create opportunities for interracial and intercultural experiences. Because what we know is that children that have these experiences show less prejudice and are more culturally sensitive. So you could attend events in other areas or neighborhoods. If your own neighborhood or city is very homogeneous, seek out another city, that either is very diverse or even if it's a homogeneous environment it's an environment that is different from yours, where people look very different from your family.

Professor Vittrup: You can set up film networks or use social media connections to connect with culturally diverse networks. And so in terms of attending events outside your neighborhood, try to look for diverse areas. Try to look for whatever events or activities are going on in these areas. It could be a playground. It could be a public pool, an event at the library, festivals, holiday celebrations, sporting events. Don't just pick these cultural events because they don't have to be. What's important is the environment and visual exposure that children will get to others that look different. And the children may develop new friendships. If this is a place that you start going on a regular basis, they might pick up new friends. Even if they don't develop lifelong friends from this, just the one hour that they are playing with other kids on the playground or at the pool or whatever area you've chosen, they get this visual exposure and they get used to interacting with people that look different.

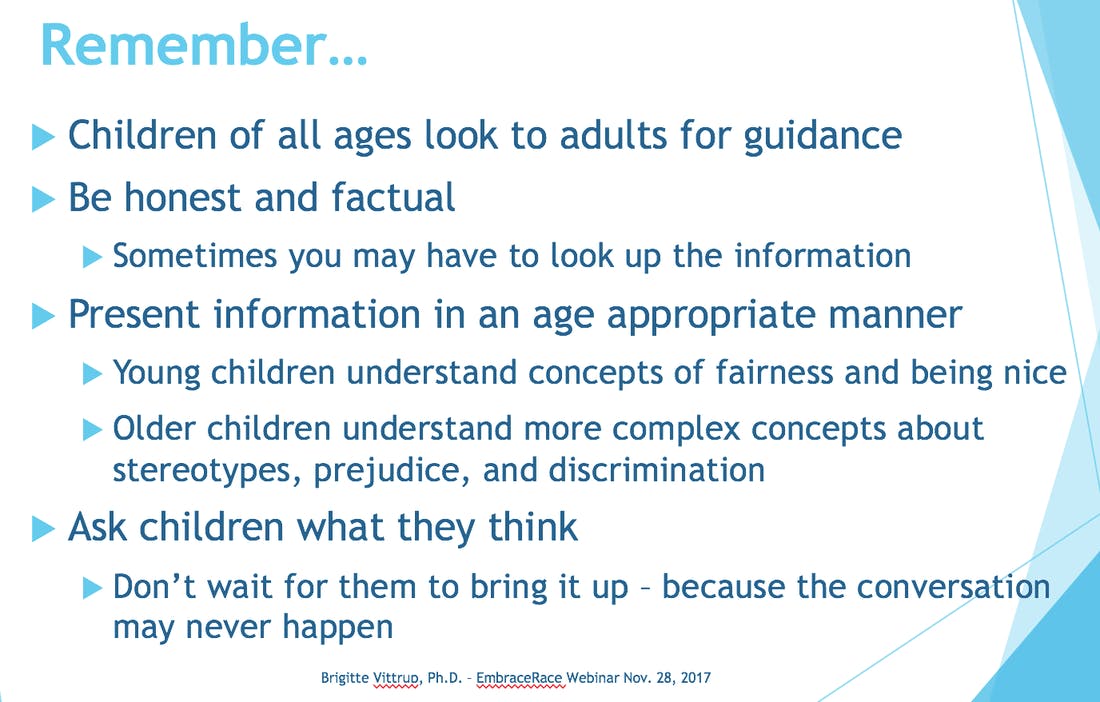

Professor Vittrup: So it's important to remember children of all ages - even when they are teenagers and even young adults - they look to adults for guidance and parents are very important providers of this guidance. It's important to be honest and factual. Sometimes you might have to look up information because you just don't know. And that's okay. It's okay to say, you know what, I don't know that but let's go look it up.

Professor Vittrup: It's another way to teach children that we should educate ourselves about the lives of others, about the experiences of others, and then teach them how to find reputable sources for this information. Present information in an age-appropriate manner. Again, conversations you have with a 4 year old versus a 14 year old, they are going to be very different. But young children understand the concept of fairness and being nice. If you've ever tried to have two children share a cookie and break a cookie in half, you know that they know what's fair and what's not fair. They want everybody to get the same amount. And so it takes some of these messages of social justice and equality and really just boil it down to fairness and being nice and have these conversations. Older children are going to have a more complex understanding about these concepts related to stereotypes and prejudice and discrimination.

And ask children what they're thinking. I always say don't wait for children to bring it up because then the conversation may never happen, especially because so many of them have been raised in households with this colorblind ideology and there are no conversations. So they are likely to just try to figure it out on their own and then that information becomes distorted. But certainly have these conversations. They might be uncomfortable when you first start, but eventually as you get used to it, as you start having more of these conversations, they will become more natural to you. So with that we can open it up for questions.

Community Q&A

EmbraceRace: Brigitte, thank you very much. We have a lot of good questions. So we're just going to jump right into them. You made a point of saying, and we talked beforehand about how this issue is relevant to all racial demographic groups in all places and so on. I want to start with a couple of questions that really underline that point.

So one question is this: "My daughter is the only black girl in her preschool class." Can you make suggestions for raising children of color who are racially isolated in their schools, neighborhoods?" Sometimes even in their families, in the case of some transracial adoptees. What what kind of suggestions do you have for them?

Professor Vittrup: Yeah I think that's a really good question. First of all, it's certainly important to make efforts to develop this child's self-esteem and identity and feel good about being who you are even though you look different from others. And really, regardless of the color of their skin and whether or not they are isolated or not, it's important to have these conversations with children about how there are all kinds of people that look very different. We have to embrace these differences. But when teaching a preschooler, you have to be careful not to put too much on them when they're little. But you can still start talking about how, yes, you look different from the others, and then make sure to create opportunities to further the conversation and learning from there.

If would also say that if you are raising your black daughter in a neighborhood that's mostly white, or the child is attending a school that's mostly white, do take her to other areas because it is really important for children to see others that look like them in order for them to develop a positive racial identity. Certainly having some of these conversations, reading books where they can see people that look like them, taking them to areas where they can see people who look like them. But still having these conversations about how people look different, sometimes people are treated differently because they look different. And as the child gets older, that's when you have to have more of those conversations about, what do you do if somebody calls you a name because of the color of your skin? What you do when somebody says x y z? Try to expose the child to as many environments as possible so that she can see people that look like her.

EmbraceRace: Thank you, Brigitte. And let me ask a question from Amy which could be relevant to a child in a similar circumstance. "Do you have any suggestions on how to support non-white children who experience discomfort from interacting with their white peers? Kids notice racial and cultural differences early on and many are not nuanced in avoiding comments that ultimately are micro-aggressions.

Professor Vittrup: And so again it depends on the age of the child. But the more exposure that the children get, taking them to other environments where they can practice interacting with others, and then talking to them. Just give them a couple of pointers. If somebody says this to you, here's the response. Why did you call me that? That's not really nice? If it's younger children it's that's not really being nice. Or find look for common ground. That's what we tell adults who are uncomfortable interacting with others. What do you have in common? What can we talk about or what can we play that we all like to play? But certainly have these tougher conversations, too, you know, sometimes people just say mean things and it's not OK.

EmbraceRace: That's a great answer. Here's another great question. How do you present positive counter examples to racist stereotypes while avoiding the racist "one-of-the-good-ones" trope?

Professor Vittrup: It's both/and. So we can show counter examples - positive role models of, for example, a black principal or a Hispanic community leader, where kids can see examples of people in leadership positions. Especially for minority children so they don't just see examples of people in, for example, blue collar jobs and then they see the leaders as the white people. That affects their career aspirations. We see that too. That doesn't mean that you're showing negative examples of others. You can still show positive examples of all of them, but really exposing kids to the counter examples. And sometimes that means going outside of your area or finding videos, finding books, talking about it.

EmbraceRace: So here's another question. I work in a school where the only Hispanic staff member works for the cleaning company. The teachers, the administration, with one exception, are all white. How do I talk about this with the kids in my class, which is fairly diverse?

Professor Vittrup: This is interesting because this has come up in some of my research with teachers, too. Many teachers are afraid to start talking about this. But I think you do have to point it out. You have to have these conversations. That doesn't mean that you start pointing out the custodian at your school who's the only Hispanic staff member. You can start by selecting a book or selecting a topic to talk about and then bring it into the conversation. And ask the kids, what do you think about that? We have to remember, that just because you're Hispanic doesn't mean that you have to be a custodian. There are lots of Hispanic people who have different careers. And also, there's really nothing wrong with being a custodian. You just have to just get down to it and talk about it.

EmbraceRace: So here's another one, a hard question. Is it better for a child of color to be in a majority white school that is in their neighborhood and part of their immediate community or to be in a school out of district that may be more diverse and integrated but not in their neighborhood? Tough choices.

Professor Vittrup: We do see that the more integrated and the more culturally diverse the environments are, children are reaping the benefits of that. And not just where there are more people that look like me, whatever color you are. But just that there is a variety, so that they can see that and have those interactions. I do know people that have specifically asked for transfers in order for their children just to be in a less homogeneous school and people that move to raise kids in a more diverse neighborhood. It obviously has to be practical for the family, but certainly there's a lot of benefits to that.

EmbraceRace: So a well-grounded assumption of much of what you've said, Brigitte, is that we need to be together, right. It's very beneficial to have diversity in the immediate environment and it's more difficult to raise inclusive kids when we don't have it. You're giving advice on what to do if that's not the case. But the presumption is that if that is the case, that is a condition that can be very beneficial to the development of inclusive attitudes and so on. And we also know that that's not necessarily enough. You think about familiarity breeding contempt. We have a couple of questions that really get at that.

One person uses the term gentrification. The other notes that there's a lot of overlap between racial identity and class status. And in both cases the concern is that overlap. So poor and low-income people in diverse settings, certainly in urban settings, are more likely to be people of color. And relatively well-to-do people are more likely to be white. And that juxtaposition can breed stereotypes. They're asking, in those diverse but not necessarily integrated settings, how do they support their children in warding off the stereotypes and being inclusive?

Professor Vittrup: You bring up a good point and we can look at history to explain some of that. We can also look at current zoning issues that separate people in terms of race and in terms of class. Even though those are related, we still have to look at both aspects. There is that perception, and I see it among a lot of whites who say this is not a race issue, it's a class issue. But a lot of times it's both or either.

You have to educate children about that as well because there's a lot of stereotypes about low-income people. And I think it's just as important for children to have exposure to those environments. Unfortunately, in the poorer neighborhoods, the schools don't get as much money because of the way that we do school funding, and so then people don't want to move to those areas because the schools are less desirable. And so it's a really hard issue to tackle. I think there's a lot of education that needs to happen because, yes, we can sit here and say you why don't you move and let's all integrate and mix it all up. And in reality, that's not going to happen. So it's important that we educate children and give them those exposures and help them think about it.

EmbraceRace: Another question. How can I help my white children to do the right things with their friends who are people of color? How can I encourage friendships without causing harm to children of color?

Professor Vittrup: Certainly, you don't want to tell white kids, "Go be friends with these black kids because they're black and you need some black friends." Friendships have to happen organically. But the more exposures they have, and you can teach them to look for commonalities. And it's really important because I think white people often don't have enough conversations because race is less salient to us. And so we're not constantly being forced to talk about it and to think about how we're being judged based on our race. And so I think it's important, especially among white families, to help these conversations, to help them understand what other people are experiencing.

You can have, for example, a black family that's very well to do, and so money is not the issue. That doesn't mean that they're not facing those biases and the psychological stress of always having to wonder, how am I being judged by others. It's important to educate children about that and to really encourage them to seek out a wide variety of friends, diverse friends, and help them see the benefit and the value in getting to know people who are different, not just racially. It could be ability, it could be immigration status, it could be anything that makes somebody different, or the parents have a unique job, or whatever it might be that they really learn to value that. Here's somebody who is different. I want to get to know this person.

EmbraceRace: Brigitte, we have a couple questions that get to frequency of contact. You gave a number of suggestions in your presentation some of which, if you live an hour away from the closest place that offers some meaningful diversity and the kind of events you're suggesting families go to, then presumably that's not going to happen on a daily basis and may not happen on a weekly basis. Which raises the question of, well, how do I think about that? How often? For example, a white woman with white children who has extended family that is multiracial. So once, twice, three times a year they might get together. And there are close cross-racial friendships among children and so on, but it only happens one or two three times a year. What work does that do? Is that not nearly enough? How do we think about that?

Professor Vittrup: Given that these are family members and actual friendships, when the children are actually creating friends, that's very powerful. It's a very powerful influence. But in the long term, it's not going to keep all of those other messages out and all those external influences but certainly it helps. And in the meantime, you can also have these conversations about social justice, you can set them up with a pen pal. Certainly for people that live very rural areas where they would have to drive that far, it's not something you're going to do every weekend. But certainly there are those opportunities. Over time, coupled with the conversations, they are going to help.

I grew up in Denmark. And so it was probably about 98 percent white when I was living there. I'd been living in the U.S. for a while before I was ever made aware of, Oh yeah, I'm white. It was never something I had to really think about. So I was somewhat naive about race relations in the United States. But there were always these very strong messages from my family about social justice and equality. I have a cousin who is Korean, but that was really the only diversity I was exposed to for many years. But then we talked about immigration and things going on in other countries. And so those messages still got through. So there are still opportunities even if it's not close, actual physical interaction on a frequent basis.

EmbraceRace: Brigitte, our time is almost up but we want to get to a few more questions. This one in particular I fine hugely important. Many of us talk a fair bit about the educational and open social benefits of diversity. And yet I suspect that a lot of people simply don't believe it, a lot of people of all stripes, and frankly, especially white middle-class and affluent parents. And we know this from polling. 70 percent of people will say, yes, diversity is a value but it's clearly a low priority value. It comes in sixth and seventh behind all these other things. So if all things are equal, they would choose the more diverse school. But all things are never equal. And so, in effect, diversity is rarely a thing that moves people. So this person asks, I appreciate the point made about children reaping the benefits of attending a more diverse school environment. Can you speak more to what some of those benefits are because, unfortunately, in my experience, the schools that are more diverse have less financial resources and less academic rigor when compared to schools that are mostly white.

Professor Vittrup: I really think that we have to remember that it's not just the actions. It's not just the experiences. It's not just the words. It's all of it together. You have to have certain experiences and then you have to talk about it. And so we have to acknowledge that white people like me have the privilege of not having to really see race or consider it or be concerned with diversity, unfortunately, and I think that's why you see that it ends up being a lower priority. But ultimately we all benefit from it. And I think that in terms of the schools that's an important conversation you have, too. It leads into these social justice conversations about why do these schools not have as many resources. What is going on and what can we do? It's not something that any one individual or one family can solve. But the people that speak up against inequitable schools and get involved with organizations like EmbraceRace, the more progress we can make over time. We have to bring awareness of these issues and our children need to be aware as well.

EmbraceRace: And you know Brigitte, I just wanted to add one quick note to that. The public school population, right now, is a majority kid of color population. As you get younger and younger, you get more and more brown, as they say. So all children 5 and younger in the United States are majority kids of color. And that will continue to be true, this is not primarily about immigration for example, so it doesn't matter what we do to our borders. It's mostly about the youngest populations being immigrant populations or those one step removed from immigrant parents, immigrants themselves. So the well-being of that population is absolutely central to the well-being of the United States and the relationships among us all is critical as I said at the outset to whether or not we thrive as a multiracial democracy, there's no way around that.

Closing out, Brigitte, you talked about your Danish background. There's so much discomfort among people in the U.S., and especially white people, in talking about race. So I'm wondering if being Danish was kind of a superpower for you. Whether you were able to observe people's responses that you hadn't necessarily learned?

Professor Vittrup: To a certain extent I think yes. In school [in Denmark] in my social science classes, we learned about the Civil Rights Movement, we learned about Jim Crow laws. But it was taught as if, that was then but it's all better now, and everything is great. I learned that but then when I moved to the U.S. I saw, wait, it's still bad.

But I still had this privilege of not having to constantly consider my race. It was one time that I was in school doing my undergrad and I was working at the student union and and I was doing an event for this black sorority. I was a cashier there and at one point I overheard a girl say, "Oh no you don't pay me, pay this white girl down at the end." And it was a revelation to me, that all of a sudden I had become aware of my race. And so that opened my eyes to some of these things. And I started studying race in graduate school because I became more interested in it. Now that I'm married to a black man and have biracial children, it's become even more salient and relevant to me. But, yes, when I moved from Denmark to the U.S. it was obvious that, unlike what my textbooks taught, the Civil Rights Movement hadn't solved this country's race problem.

EmbraceRace: We're at the end. Thank you all of you who joined for participating, for the great chat and fantastic questions. Bridget thanks especially to you for sharing so much that you've been learning and experiencing in your work and life.

Professor Vittrup: You're welcome. I enjoyed it.

EmbraceRace: Take care everyone! See you again soon!

Brigitte Vittrup