Black Like Me?

That feeling you get knowing you sometimes get treated better because others are treated worse.

by Andrew Grant-Thomas

Puzzle #1

I had quite the heavy foot as a young driver, and my 1984 Toyota Tercel coupe hand-me-down was happy to oblige. Sammy Hagar’s “I Can’t Drive 55” could’ve been my anthem.

Loved speed. Still do. But I’ve slowed down a little bit. With age and experience, wife and/or kids sometimes in the passenger seats, and the just-in-time obsolescence of my teen brain, nowadays I’m well aware of the dangers of excessive speed.

Back then? Not so much.

Happily, my penchant for speed didn’t lead to any serious accidents, injuries, or other big trouble. But I did get stopped for speeding. Oh yes. Between the ages of 17 and 24 I‘m guessing I got stopped maybe 10 times, mostly in my hometown of New Haven, Connecticut. Which is a lot considering that half of those years I didn’t even have a car.

How many tickets did I get? One, maybe two.

While the term “driving while black” has been around at least since the 1990s, African Americans have complained for much, much longer that police officers target us for traffic stops and searches. The empirical evidence on this is clear and backs up the claim.

So how does a young black man get stopped by New Haven’s finest 10 times and get ticketed only twice?

Puzzle #2

In March 2012, while living in Columbus Ohio, I was diagnosed with a mega tumor of the thymus gland (front of your chest, between your lungs). A month later I had surgery to remove it.

Unfortunately, the surgeon nicked a thoracic duct, which left me leaking too much fluid post-surgery. To coax the offended duct to heal itself, my care team put me on a special IV diet. They assured me that “9 in 10 times that takes care of everything.” Well, somebody has to be that 10th time.

Another surgery followed to fix the problem. It didn’t. By the time I got home, an expected five-day hospital stay had stretched to seven weeks, two cities, 1,000 miles of driving, and an army of medical people.

It was a miserable time. But through it all I was treated well by almost everyone I dealt with. Meaning that I was treated the way all patients should be treated, but many aren’t. We’ve all heard the horror stories about arrogant doctors, rude nurses, indifferent social workers, and more.

My story was different. From the surgeon and specialists to the nurse practitioners and nurses to the volunteers, they heard my concerns, answered my questions as best they could, and took my wishes seriously. My friends, my wife, and I were even able to influence the course of my treatment in important ways.

At one point, I took an ambulance ride to Philly. The city is home to one of only three hospitals in the country at the time that performed the procedure that finally allowed me to go home. I wanted to go to Philly, needed to go, but would my insurance cover the costs of the 1,000-mile roundtrip? If so, how much of it? How much of the God-knows-what cost of that ride — with three ambulance attendants!— would fall to us? I needed to go, but I also needed to know.

“Don’t worry about it,” my surgeon said. I never even saw a bill.

Even accounting for insurance status, income, age, and all that, African Americans — people of color, in general — are much less likely than whites to receive high-quality care in US hospitals, clinics, and doctors’ offices; more likely to undergo unwanted procedures, such as lower-limb amputations for diabetes; and less likely to be treated with common decency and respect. This finding has been well-documented at least since 2002, when the Institute of Medicine published Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.

So how does a black man of modest financial means come to enjoy the upside of “unequal treatment” in two major US hospitals?

How to be Black — and get away with it

I’m convinced that a big part of the answer is that while I look black and identify as black, I’m often not seen as “black” in the ways a lot of people understand blackness in these United States.

For one, there’s how I sound. I was born in Jamaica and came to the US at age 7. For years, some of my white peers would insist that I was “Jamaican, not black.” I lost the accent long ago and these days people rarely guess that I have West Indian roots. When someone does, it’s because of how I pronounce a word here or there. I’ve been told I sound vaguely British. I’ve been told I sound “white.” Point is, apparently I don’t sound like most “black Americans.”

I was a very polite kid. Parents and teachers often told my mother how well-behaved I was — in much the way Joe Biden once described then-Senator Barack Obama as “articulate and bright and clean.” Course, Obama is those things; on my best, most hygienic days, I am too! However, what makes these attributes literally noteworthy is that we’re black men. A white guy with Obama’s smarts, character, and poise? Very impressive, but not news. A black guy with all that? Hey, now! In a society that expects only the worst of black men, that’s man-bites-dog stuff.

See how that works? We like to say that seeing is believing, but, very often, it’s the other way around: we tend to “see” what we believe we’ll see, what we expect to see.

When those police officers in New Haven pulled me over, it was all yes-sir/no-sir contrition from me. Not much else for me to do. When you’re stopped for going 53 in a 25-mph zone on a narrow, winding, suburban street, best not to “cop” an attitude. Point is, I gave those officers something quite different than they might have expected from a young black man — and some of them rewarded me for it.

The hospital case is more complicated. By that time in my life I had a lot going for me. I had great health insurance. An awesome support network led by an attentive partner and highly educated friends. Professional titles and degrees are gold in higher education and all my time was spent in university hospitals. My doctor spent 10 minutes talking string theory with my (white) British theoretical physicist friend who came from London to spend time with me. You think that didn’t add to my social capital? This highly esteemed white surgeon insisted on calling me “Dr. Grant-Thomas.” As a result, so did his staff.

I wasn’t daunted by the doctors’ expertise and felt entitled to advocate for myself. My wife, my friends, and I had a kind of class-based capital that allowed us to question and even challenge the medical staff in ways that seemed to impress rather than threaten them or tick them off.

Again, I had a lot of stuff in my favor. But all that took on a special charge in light of my racial identity. It was my blackness that made me stand out in the eyes of police officers and doctors alike, that recommended me for their care and generosity. In the streets of New Haven and hospitals in Columbus and Philadelphia, my blackness was the secret sauce, never explicitly acknowledged, that made the various flavors of my privilege POP.

At age 23, driving too fast in a downpour while trying to read a map in the pre-GPS days, I came upon a sharp curve in the road. My balding tires couldn’t hold the curve. My car swept across the road, jumped an island, and knocked down a large street sign.

A police officer appeared. I was shaken, mortified. No, sir, I haven’t been drinking. He escorted me to my destination. No ticket. What about the sign? “The city can fix its own damn sign,” he said.

POP!

The roots of my “exceptionalism”

I am what the writer Earl Ofari Hutchinson has called a “racial exceptional black” — an African American some whites, blacks, and others see as unlike most other African Americans in at least some important respects. This is a weird and awkward status to have, knowing as I do that the benefits of racial exceptionalism that sometimes come to me spring from diseased soil.

President Obama registers as unusually “articulate and bright” by any measure, but his star positively dazzles against the bleak presumption that black men are inarticulate and stupid. I was a soft-spoken and well-behaved kid. However, the effusive praise adults regularly gave me makes more sense in light of the fact that many people view black boys as less innocent (and older) than same-age white kids, and that even the faces of five-year-old black boys can make whites feel threatened.

The social and cultural pathology that led Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson to see Michael Brown as a “demon,” and shoot him repeatedly, also helps explain my unusual experiences with police officers and medical staff. Make no mistake, racial demonization and racial exceptionalism are different fruits from the same poisonous tree.

Mind you, I’ve got plenty of the usual, shit-gets-tiresome black-male stories to tell. The middle school history teacher who accused me of cheating because, he said, my project was too good for me to have done myself. The police cars that slowly shadowed me as I walked across campus at night. The white Master’s student who challenged a departmental administrator to explain how I got into the PhD program when he didn’t. (Yeah. Seriously.) The elderly white woman who mistook me for an elevator operator. The tightly-clutched purses, waaay too many to count, accompanied by a lips-pressed determination to avoid eye contact with me.

I could go on.

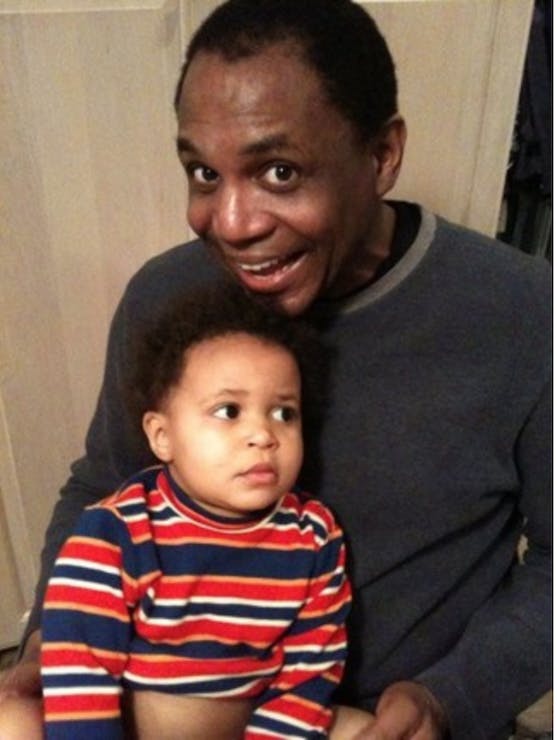

Still, it seems that I’m generally less likely to trip people’s threat alarm than most black men are. Depending on context, it might be my hyphenated, not-black name; my soft-spoken, vaguely British, “white” voice; my West Indian origins; my PhD from an elite university; my multiracial wife and kids; my ease with most white people; my round, frequently smiling face; combos of all these… who knows, exactly. What’s clear is that, for some people, these notes form a more resonant chord coming from a black man than they might otherwise.

I’m not gonna lie to you. I’m just fine having missed out on all those tickets. And I recall the wonderful care I got from my medical team with deep, deep gratitude. But I also know that names, accents, nice degrees, and anything to do with skin color are bullshit reasons for giving a young speed demon a break or treating cancer patients especially well. And they’re truly godawful reasons for not doing so.

Addendum

A few readers have misunderstood the point I’m making, which is on me. Let me make it plain.

While I’ve sometimes been stereotyped and stigmatized as a “black man,” there have also been times when I have been treated unusually well by people, especially some whites, who I think effectively “reward” me for not conforming to their low expectations of black people and black men. This might be seen as a kind of privilege, but, if so, it’s one grounded in a very unfavorable view of black people that at other times punishes me too. Not to mention that some of the characteristics that “earn” me this reward — the way I sound, my smiley face, maybe even my hyphenated name — are ridiculously superficial.

Andrew Grant-Thomas