Beyond War Cries and Tipis: A Real Native American Story

By Sarah Sunshine Manning

Sarah, as a third grade student.

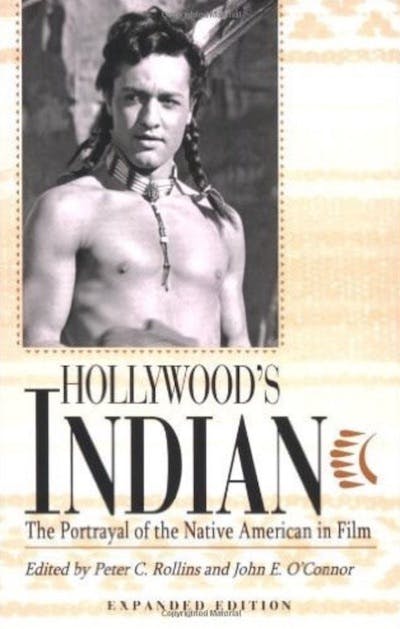

We live in a society obsessed with the Hollywood “Indian.” The Hollywood portrayal that promotes limiting, and even dehumanizing representations of Indigenous Americans as savage relics of our past: stoic, barbarous, noble, and disappearing. My life looks nothing like Hollywood portrayals of the leathered and feathered Indian. In fact, real and contemporary Native American experiences turn the Hollywood Indian stereotype on its ugly head.

This is my story.

Life on the reservation

For most of my childhood, I grew up on the Duck Valley Indian Reservation on the Nevada-Idaho border, a beautiful and pristine piece of land removed from luxuries like fast food restaurants, grocery stores, shopping centers, movie theaters, and most other urban comforts. Of course, we had some amenities and businesses on the reservation: a school, a post office, a hospital, a couple of cafes, and tribal government offices.

My childhood home on the reservation stands in the wide-open country, encircled by our family ranch. I grew up riding horses and branding cows, with open fields and dirt roads in all directions. I had a privileged childhood, rich with cultural expression, ranch lessons, and a strong sense of family and community.

Riding horseback on the family ranch.

On the reservation, I was surrounded by brown faces of all shades. Aunties, uncles, grandmas and grandpas, sisters and cousins, and my own parents. I always felt safe — and seen. These were my relatives and this was my home.

Aside from English, I heard the Paiute language spoken often on the reservation, and even more often in our home. The Shoshone language was also spoken in the community, as our reservation is home to both the Shoshone and Paiute tribes.

I grew up participating in unique cultural events on the reservation, like ceremonies, gatherings, and dances. Yet I also grew up doing things that many other American children do, like playing basketball, taking piano lessons, and selling Girl Scout cookies. Early on, I knew who I was as a Newe’ tzea’a, a modern-day, Shoshone-Paiute girl.

People didn’t seem to know much about Native Americans beyond what they saw in old Hollywood films…villainous Indians shrieking in the background, wielding bows and arrows, and maybe occasionally speaking broken English. “Wild” Indians with feathers in their hair, wearing headbands and fringed clothing, living in tipis.Life in the cityI also spent some of my early childhood years in an urban area — Boise, Idaho — as my mom completed her college education there. As a first grader I was one of a few brown faces in a sea of pinkish faces. There was one African American girl in my first grade class, Stacy, and I was aware that in a class down the hall there was an older Native American boy, Alex. I had a crush on Alex. He was like me.

While I wasn’t exactly aware of just how different I was then, as a 7-year-old, I recognized other brown people around me, and I definitely noticed the “Indians.” In public places in the city, my mom would say in the Paiute language, “Punni! Newe’!” “Look! Indians!” And we would quickly look over at them, happy. It was rare that we saw some of our own there in the city.

While my mom was attending college, we traveled between Boise and the reservation on weekends. My dad maintained our home and worked on the reservation, and so we went, back and forth — to the city, to the reservation, back to the city, and back to the reservation.

This was my life for five years, from the ages of 3 to 7. The summer after first grade, we moved back to the reservation. I later realized that this constant transitioning helped me adapt to change and embrace the beautiful diversity in the world around me.

Yet, it was while living in the city of Boise that I became aware of my differentness as others became aware of my Indianness. I later realized that I wasn’t quite what the typical American expected from an “Indian,” and many of them didn’t even think of me as an Indian at first. It always took some convincing to prove my identity.

To them, I might just as well have been Sarah, the little girl with black hair and brown eyes. To them, perhaps I was even Mexican, as across the country Native Americans are often mistaken for Mexicans, given our brown skin and dark features. Anything but Native American.

People didn’t seem to know much about Native Americans beyond what they saw in old Hollywood films. Western films, where the cowboys fight the Indians — villainous Indians shrieking in the background, wielding bows and arrows, and maybe occasionally speaking broken English. “Wild” Indians with feathers in their hair, wearing headbands and fringed clothing, living in tipis.

As a 7-year-old Native American girl, I didn’t wear feathers in my hair, I didn’t wear long braids, and I never lived in a tipi. I definitely didn’t speak broken English as a first-grader in the Gifted and Talented program. For much of my childhood, I had a pixie-style hair cut with bangs, and my mom dressed me in cute outfits from JC Penney and hand-me-downs from my older sisters.

After that, Clay, a white boy I also had a crush on (hey, I guess I was boy crazy), introduced me to his big brother like this: “This is Sarah. She’s a…,” and then he paused to cup his hand over his mouth, …“‘…Woo-Woo-WOO!’ — Indian.”

The day we dressed as “Indians”

One day while attending a summer program in the city, I showed up with my mom in our powwow regalia, clothing we wear on special occasions, mostly to dance — you guessed it — at powwows. My mom fixed my hair in two braids with minks hanging down from them. I wore my calico-print wing dress, a shawl, moccasins, and a beaded belt and leggings.

My mom wore her buckskin dress, her hair in two braids with minks, just like mine, and an eagle feather centered in the back of her head. She also wore beadwork and moccasins.

My mom dressed in traditional powwow regalia.

All the kids gathered around us in awe and touched our clothing. They asked questions, and my mom, in training to be a teacher at the time, gracefully shared information about our culture and our identity as Native Americans. After that day, my peers finally saw me as an “Indian.”

After that, Clay, a white boy I also had a crush on (hey, I guess I was boy crazy), introduced me to his big brother like this: “This is Sarah. She’s a…,” and then he paused to cup his hand over his mouth, just like the fake Hollywood Indians do in the movies, and made the Hollywood Indian, hand-over-mouth, war cry “‘…Woo-Woo-WOO!’ — Indian.”

— “She’s a- ‘WOO-WOO-WOO!’- Indian.” --

Mockery of the “Indian war cry.” Real Native American tribes never used the hand-over-mouth gesture.

At the time, I wasn’t offended by his gesture even the slightest. I was honestly sort of pleased that he saw me as an “Indian,” albeit a stereotypical one. He still saw me, if only minimally, and in a distorted way.

It was many years later, as a young adult, that I realized that Clay’s mockery of Indians was rife with demeaning and reducing stereotypes. It took me years to even distinguish clearly between stereotypical portrayals of “Indians” and who we really are.

And much later, while taking college courses, I began to understand why these demeaning stereotypes existed in the first place, and how these sorts of stereotypes manifest themselves in everything from historical U.S. documents to racist Hollywood portrayals to Disney movies, toys, Thanksgiving plays at schools, Halloween costumes, Victoria’s Secret models wearing headdresses, Boy Scout rituals, Indian mascots … The list really does go on and on.

The hypersexualized stereotype of a Native American woman in a Halloween Costume.

But still, in my developing sense of self, as a 7-year-old Newe’ tzea’a, it felt as if I was actually being seen by Clay and my white peers as a “real” Indian. Finally. Well… almost. I was seen as a stereotype, which, really, means that I was hardly seen at all.

To be seen as a stereotype is to be unseen

Today, as a parent and an educator of Native American youth, I understand that the phenomenon of “almost” being seen — amidst stereotypes and virtual invisibility — is extremely problematic. In fact, a growing body of academic research confirms the psychological harms of such pervasive and stereotypical imagery of Native Americans, stereotypes which are deeply imbedded in our society.

Political cartoon inspired by a real-life event, as a Native American man protests the Cleveland Indians mascot while confronting a Cleveland Indians fanatic.

As the real-life stories of Native Americans can attest, we are not Hollywood savages of the past and we are not hypersexualized Pocahontas perversions. We are modern and multifaceted. We are diverse and complex. And, contrary to what history books imply, we are still here, wearing blue jeans and t-shirts, driving modern vehicles, and occasionally wearing feathers in our hair. Yet, still, we are waiting, and sometimes even fighting, just to be seen.

Sarah Sunshine Manning