A Wrong Way to Cosplay

By Perfecta Oxholm

A post about kids and costumes might seem out of season but I live in San Francisco; kids in costume are year-round here.

A little over a year ago, my mother-in-law got me a subscription to Parents magazine. Parents is not a magazine I would have subscribed to on my own.

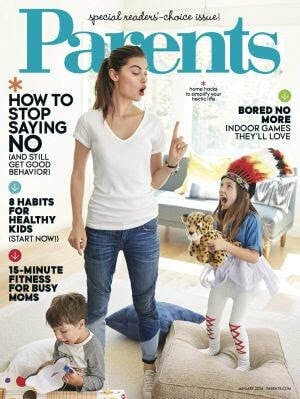

Without much knowledge about the magazine, I assumed it offered a lot of mainstream, stereotypical, commercialized views on parenting, which it does, but it also provides some unexpected and thoughtful perspectives. I’ve been pleasantly surprised (thanks Mom!). For example, the first magazine I received included an article on parents raising transgendered children. The January 2016 issue included ideas to keep your kids occupied during the long winter hours spent inside.

January 2016

January 2016

Do you see it? Admittedly, I did not at first. Perhaps I’ve become inured to costumes living in SF, although I think that’s too generous a reading. Rather, I think I was blind to one of the many issues Native Americans (and other people of color) have to face all too often: ignorance and disrespect of their cultural, racial, and ethic heritage.

Thankfully, many readers did notice the cover and flooded Parents magazine with comments and criticism. To their credit, Parents issued an online apology and, in the March issue, provided a little more information on the controversy, the comments, and the process behind their response. I liked a few of comments Parents shared, along with some more information I found online, so I thought I’d borrow some of the reactions and create a rough outline for digging into these issues deeper with our kids.

Starting the conversation.

Parents quoted Ilana Weitzman, a parent from Montreal, QC, who said, “The way we explain [costumes] to our sons: You can dress up as jobs or characters, but not as other people.”

I think this is great language to start a conversation with our kids about appropriate and inappropriate costume play. It’s likely most of our kids will be fine with this answer, unless they’re really committed to the costume or are older. (Older kids might want more of an explanation.) In any case, I think it’s our responsibility to provide more information to our children on why dressing up as people is harmful, hurtful, and often bigoted.

By having a deeper conversation with our young kids, I think we can nurture kids who won’t just know why it’s wrong to dress up as a Native American for Halloween, for example, but will be able to educate their peers on why it’s wrong too.

Framing the problem.

There is a ton of information online about why dressing up as a Native American when you aren’t Native— or in blackface, as a “wigger,” in “ghetto-themed” outfits, etc. — is wrong. The details of the conversation will vary depending on the event, and I encourage everyone to get more information if you don’t already know why these actions are harmful. Here, I want to a touch on a more general reason for talking about this type of offense, especially with kids: it’s abusive. We talk about this type of abuse because we need to help our kids make sense of how they are hurting other people or why they are being hurt.

As a mixed-race child, I was often on the receiving end of ostensibly harmless but inherently abusive actions. As the parent of white children, I feel it is my responsibility to make sure my kids understand how their actions can cause harm. I want them to see they are a part of a racial reality. For me, talking about whiteness and (when the time comes) providing information on the ways their racial identity impacts their actions is important in creating conscious, empathetic, compassionate kids.

Nine steps for avoiding racist costumes at Halloween

Some costumes rely on stereotypes.

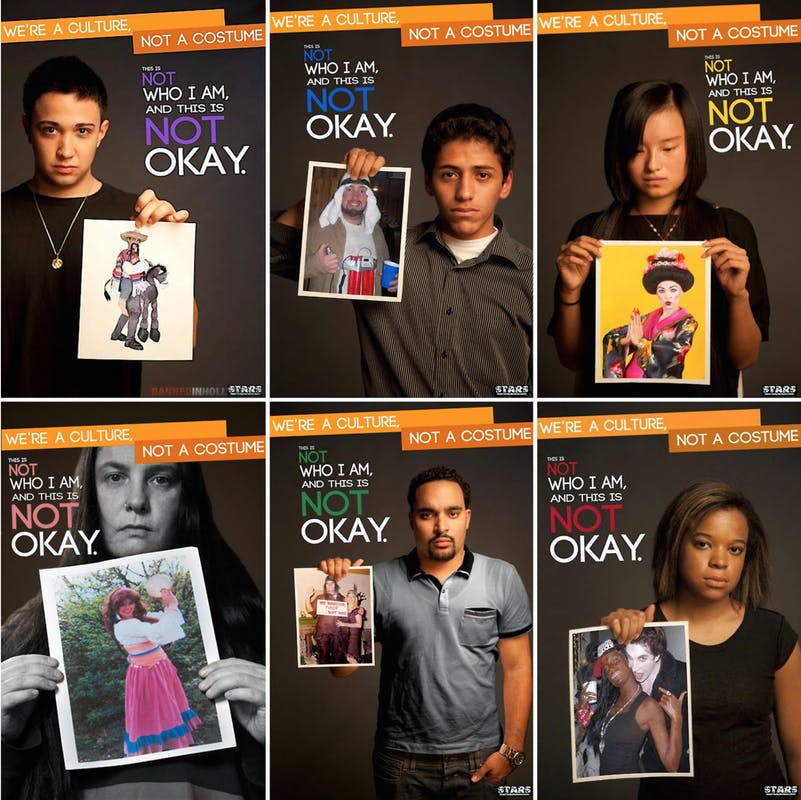

Dressing up as people is harmful because the action often directly relies on caricatures, exaggerations, and negative stereotypes. American Indians are a diverse group of peoples. Through the process of imitation, the entire diversity of American indigenous peoples is reduced to a single image. And images are important.

Stereotypes get perpetuated, or deconstructed, through images.

By dressing up as an American Indian when one isn’t, one effectively objectifies all American indigenous peoples. American Indians are not only a diverse group of people, they are a real group of people with real histories and real cultures.

“Playing” a person or group of people necessarily caricatures their histories and cultures. “Playing” another person or group of people creates fictionalized versions of real people, and this degrades the groups or individuals depicted. Treating people as objects removes their identity and their dignity.

We see this in the setting of the Parents January cover. As many readers pointed out on the Parents Facebook page and on their own websites, the issue is not only that the child is dressed up as a Native American, but that she is acting “wild.” Dr. Debbie Reese from American Indians in Children’s Literature told Parents, “Depicting a bored child, in a toy headdress, clearly screaming, suggests “wild Indian.” Turning a person or people into a game, diversion, or costume, inevitably relies on outdated and offensive stereotypes, in this case depicting Native Americans as “wild” or unmanageable.

Explaining how this concerns us all.

There are very clear reasons why it is inappropriate for a non-Native American to dress up as a Native American. Most have to do with history and power.

As parents, I don’t think we should rely on schools to educate our kids on the historical roots of white racial dominance and structural inequality. Yet, I think these pieces are foundational to understanding the bigger conversation and controversy surrounding an image of a white child wearing a Native American headdress as a costume.

It’s not just an issue for Native Americans. It’s an issue of racial, cultural, and historical ignorance. An ignorance that can create indifference to the way social inequalities and suffering have been structured along racial lines. And that indifference can permeate our children’s worldviews.

For parents working to create more racially conscious and compassionate children, I think we need to remember to be conscious and compassionate with ourselves, and our peers, too.

I am a person fully committed to finding ways to address racism, white supremacy, and structural inequality.

I’ve spent a large portion of my life thinking about race and inequality, almost a decade educating myself on critical and postcolonial theory and the history of American racism, and I have been on the receiving end of overt and micro racial aggressions. Yet, I still catch myself defining race (consciously and unconsciously) as White, Black, and Latinx AND missing fairly obvious racial discrimination. I think this tendency to limit my racial paradigm is one of the reasons why I did not see the implications of the child in the headdress, among the many other harms my racial blindspots obscure.

One of the things I love about focusing on race and parenting is that both ask us to continuously grow into better versions of ourselves. Of course, the flip-side is also true: both can bring out the worst in us. This is where I think compassion becomes so important. We are going to do the wrong thing so often, I think the only way we can commit ourselves to the long haul is to be gentle with ourselves and with each other as we learn to expand our fields of vision to match our circles of concern.

When we acknowledge our imperfect process, honor our willingness to return to the work despite our failures, and have the humility to learn from those around us, I think we make space for a new reality — an emergent reality where our racial justice seeds can begin take root.

Perfecta Oxholm