A Broken Deal

What a white boy taught this black woman about resistance

by Autumn Allen

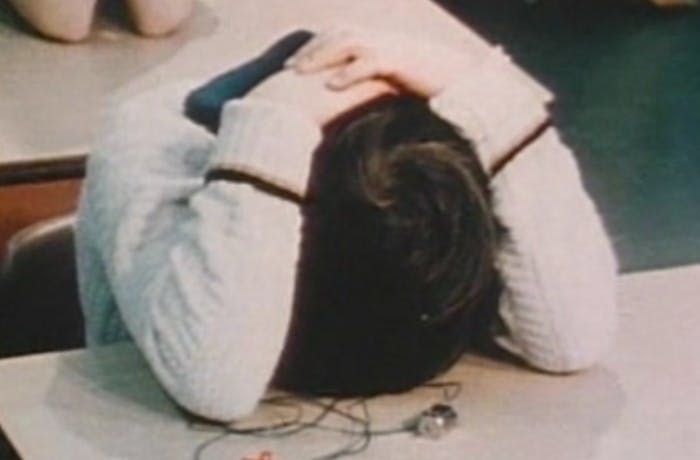

A child reacts during the original blue eyes/brown eyes experiment in 1968.

Our homeschool coop tried a version of the blue eyes/brown eyes exercise in the 6- to 10-year-olds’ history class. I knew it would be interesting, so I settled in to watch, not guessing how much I would learn.

The two parent teachers had cookies, but only the brown-eyed children were allowed to have them. The blue-eyed children sat empty-handed while the brown-eyed children enjoyed their cookies. Most of the blue-eyed children waited patiently, with hurt and confusion evident on their faces.

After the brown-eyed children had finished, the blue-eyed children were told to come up to get a cookie. They came eagerly, except for one boy named Mark. His bright blond hair fell over his angry eyebrows.

“Don’t you want some?” the teachers asked him.

He shook his head angrily, staring past them in indignation.

They turned their attention to the other blue-eyed children.

A young woman reacts during a blue eyes/brown eyes exercise with Jane Elliot. Elliot lambasted her for walking out, a privilege people of color do not have in real life.

“Okay, it’s your turn. Line up for your cookies. Oh — and we just need you to pay one penny for your cookies. Do you have a penny?”

Shoulders drooped and hopeful eyes looked down to the floor. One boy dug in his pockets, hoping he could meet the new rule, so focused on getting a cookie that he seemed not to notice that the rule was made specifically for his kind.

It’s not just the recognition of injustice. It’s the moment of realization that the whole system is corrupt, and that participating in the system keeps you at its mercy.

“Okay, okay, we’re going to give you a penny so that you can get a cookie.”

The children stood in line, taking a penny from one teacher and paying it to the other for their cookie.

Mark still did not move. His arms were folded across his chest, and his anger was palpable.

I was intrigued by this boy’s refusal to play the game. His angry sense of justice seemed familiar, though unexpected in a child so young.

The experiment lasted no more than 5 minutes, and all of the children got a cookie in the end. All except for Mark.

In debriefing about the experiment, the parent teachers asked the blue-eyed children how it felt to have separate rules. They asked the brown-eyed children how it felt to take advantage of being privileged. Did anyone feel bad when they saw the blue-eyed people being left out? Did anyone consider not eating their cookie until everyone got one?

Then I knew why his anger seemed so familiar. I have seen it most often in black boys and men, from adolescence onward. It’s not just the recognition of injustice. It’s the moment of realization that the whole system is corrupt, and that participating in the system keeps you at its mercy.

Then, they asked Mark why he didn’t come for his cookie. He seemed eager to speak.

“Because I knew that — I knew you were unfair. You were just gonna keep being unfair. You were lying.”

Then I knew why his anger seemed so familiar. I have seen it most often in black boys and men, from adolescence onward. It’s not just the recognition of injustice. It’s the moment of realization that the whole system is corrupt, and that participating in the system keeps you at its mercy.

“Well, what would you do if that was your life? Imagine if there were things you couldn’t get, or things you had to work harder for, because of something as silly as the way you look.”

“I would just steal it,” he said.

“What if there were special police and guards to make sure you couldn’t steal it?”

“I would steal it anyway. Or I would have my Dad get it. I’m the only one in my family with blue eyes.”

When asked how he would deal with such a system in real life, he thought of another way of meeting his needs. That is to say, another model of resistance.

Degrading policies at schools can cause disruptive behavior in students. Photo Source: Glogster.com.

Mark objected to the unfair system. He perceived that it was deliberately set up to advantage others and disadvantage him, and so he refused to participate. When asked how he would deal with such a system in real life, he thought of another way of meeting his needs. That is to say, another model of resistance.

Mark’s defiance (the intention to steal) can easily be misconstrued as a lack of morality. But what if it is exactly the opposite? An intense sense of morality that drives someone to resist an unjust system by any means necessary?

Resistance comes in many forms. If you subvert the system in a way that allows the powers that be to control or disempower you, it is ultimately counterproductive. The challenge is to find methods that can put you in a better position to transform the system, whether from within or without.

Mark’s defiance (the intention to steal) can easily be misconstrued as a lack of morality. But what if it is exactly the opposite? An intense sense of morality that drives someone to resist an unjust system by any means necessary?

A poignant example happens when children or adolescents have disciplinary issues in school. The social contract at the core of an educational institution includes several conditions or promises from the teacher and administration, such as: we are here to provide you with a useful and relevant education that will help you to succeed in life; we believe in you; we care about you. In exchange for these services, students offer their respect and cooperation.

What young people need — perhaps what we all need — is to retain the conscience that blocks us from being complicit in oppressive systems, while finding forms of resistance that do not result in being further disempowered.

Expressions of resistance drawn by kids in our homeschool coop

But many schools are not fulfilling those promises: the school’s resources are inadequate, the education provided is irrelevant and degrading, the teachers do not believe in or care about the students.

For example, in most schools, getting into a fight is cause for disciplinary action such as suspension. In other schools, a fight at school automatically results in involvement with the authorities, which results in a criminal record. These inequalities in the school system constitute broken promises and invalidated social contracts. And the racial and class lines along which the inequalities fall are clear. Some students respond to their schools’ inadequacies with disruptive or disrespectful behavior, for which they are then punished.

What young people need — perhaps what we all need — is to retain the conscience that blocks us from being complicit in oppressive systems, while finding forms of resistance that do not result in being further disempowered.

In these scenarios, disruptive students are assumed to be the ones breaking the contract. The effectiveness of the services are not considered to be an issue, though from the student’s perspective, it is the school that broke and invalidated the contract. Once the student has been disruptive, however, he or she can be disempowered by the powers that be. Staff can remove him from school, resulting in further problems in the young person’s life.

What young people need — perhaps what we all need — is to retain the conscience that blocks us from being complicit in oppressive systems, while finding forms of resistance that do not result in being further disempowered. We need people like Mark to remind us that we don’t always have to play the game. And we need to invent with them strategies by which to change the game.

Autumn Allen