Real Sisters and Brothers

Witnessing my children become brothers and sisters, not through shared genes but through shared experience, has been one of the most powerful parts of raising them.

By Megan Dowd Lambert

The author’s four adopted children in 2009. Photo credit: Megan Dowd Lambert

Conversations about adoption frequently omit consideration of the adoptee’s biological family and focus on parental and familial love that transcends any need for biological ties. The erasure of these members of the adoption triad is what enables adoption to be simplistically depicted as a happily-ever-after scenario for adoptive parents and children, which ignores fundamental, underlying losses and complexities. In families like mine that are formed through transracial adoption of children of color by white parents, such erasure is often compounded by a reiteration of an insidious white-savior narrative that denies the humanity of a child’s biological family, and by extension, the humanity of the child born of them.

Redressing such discourse is integral to the love I share with my children. I know in my bones that our bonds are deepened, not threatened, when we honor the love their birth families have for them and the pride they can take in their respective identities as children of Puerto Rican, African-American, and mixed Irish- and African-American heritage.Four of my six children came home to our family through the foster system at different ages, and their adoptions were finalized fairly quickly. Two of them have the same birthmother, and yet there’s no sense of hierarchy in their relationships. Witnessing them all become brothers and sisters, not through shared genes but through shared experience, has been one of the most powerful parts of raising them. That’s not to say it’s all been smooth sailing.

"I Wish I was the Only Kid in Our Family!"

The year she turned three, my now-twelve-year-old daughter, Emilia, had to quickly adjust to having not just one older brother (my biological son) who’d been in her life since she came home to our family as a newborn, but a new big sister, and a little brother and sister who all joined our family in the space of a year. It was a lot for her to handle, and we marveled at her loving openness. But one day everything seemed to catch up with her, and Emilia burst into tears of frustration and cried, “I hate everyone! I wish I was the only kid in our family!” And then after a brief pause she added each of her siblings’ names through choked sobs: “I mean just me and Rory…and Caroline…and Tayja…and Stevie! But I still hate EVERYONE!”

This outburst is one of the entries recorded in something my kids call the “funny-things book,” a journal in which I write down the often funny, and sometimes poignant, things my children have said over the years. We read it together more often than we look at any photo album, and sometimes we reference “funny things” out of the blue, or when a particular quip or anecdote fits a given moment in our day-to-day lives.

“Remember when I said I hate everyone, Mom-Mom?” Emilia has asked with a wry smile at fraught times in our busy household. And I do. But my take-away isn’t that she hated everyone, or even that she was an upset, overloaded three-year-old; it’s that she had loved her way to true and abiding sibling bonds that were stronger than her very real sense of being overwhelmed.

"Are they Real Sisters?"

Sometimes the larger world doesn’t easily recognize the truth of these bonds, or is careless in its assessment. Once at the grocery store, I was waiting at the deli counter with my two youngest children strapped into a little car attached to the front of the shopping cart while my older daughters stood nearby — until I saw Emilia wander off.

“Go get your sister,” I said to Tayja, and she scurried after her.

As the girls returned hand-in-hand, a white woman standing nearby looked at them, and then looked at me, and she asked,

“Are they real sisters?”

Her tone wasn’t friendly. It was incredulous, her voice rising to a squeak with the word “real.” I blinked. My heart sank as I realized that she saw, not “real sisters,” but a Black girl and a Puerto Rican girl. To her, their racial difference meant that they couldn’t possibly be “real sisters,” and she wanted some kind of explanation.

Trusting my gut, I refused her one and simply said, “Of course they are,” and then turned away and waited for my sliced turkey, or whatever it was I’d ordered. My quick, matter-of-fact response was rooted in advice from psychologist Marguerite Wright’s I’m Chocolate You’re Vanilla: Raising Healthy Black and Biracial Children in a Race-Conscious World regarding how to deal with such comments and questions in the presence of children. Although I found myself at odds with some of what Wright asserts throughout the book, in that moment I remembered an excerpt when she advised parents that our reactions are just as important as the comments themselves — if not more so. Standing at the deli counter I thought, if I make a big deal of this woman’s careless language, my girls may take her words to heart and question their sisterhood. If I brush it off like nothing, they may regard it as nothing, as silly as asking if rain is wet.

"I'm Real and You're Real, So We're Real Sisters, Right?"

But the interaction weighed on me as the day went on, and I second-guessed how I’d handled it, wondering what my daughters were thinking and feeling and if I should bring it up again. But before I had a chance to step in and open up a conversation, I overheard them addressing it on their own as they played with stuffed animals in the next room. It was a game in which they pretended that they were climbing up mountains (a rocking chair, a wooden chest, a set of bookshelves) in search of their home. They made their animals climb up and fall down, and they rescued each other, thanked each other, called out for help, and they tried again:

“And let’s pretend that this is a mountain…”

“And we go up the mountain, and down the mountain, and up the mountain, and down the mountain…”

“And let’s pretend that you fall down…”

“Ahhh! Help me!”

“And let’s pretend that I catch you…”

And then this:

“How could you even be pretend sisters?” Emilia asked, setting up the woman’s word “real” against her “let’s-pretend” play with Tayja.

“I don’t know,” Tayja responded.

“I’m real and you’re real, so we’re real sisters, right?” said Emilia.

“Yeah, because of adoption,” said Tayja.

And I wrote it all down in the “funny things book.”

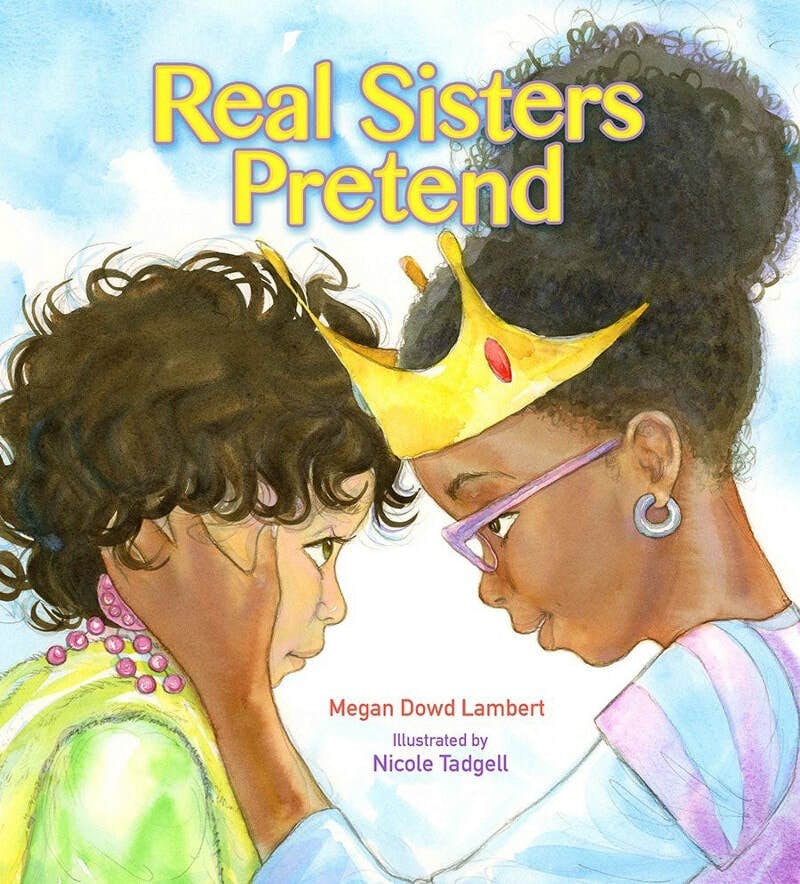

Real Sisters Pretend by Megan Dowd Lambert, illustrated by Nicole Tadgell, Tilbury House Publishers, 2016

A little more than a year ago I took this seed of a story and wrote a picture book called Real Sisters Pretend, which was published in May 2016 with illustrations by Nicole Tadgell. Out of respect for my children’s privacy I changed details about the characters’ adoption stories, as well as the family constellation (they have no other siblings in the book, Nicole didn’t use our family as models, and she depicted one of the adoptive moms as a woman of color), and I also injected princess play into the story just because I wanted to see brown girls wearing crowns in the illustrations. But the nurturing essence of the sisters’ close relationship remains the same because that’s what I wanted to center and honor in the book.

Just as biological families are often excluded from adoption discourse, I haven’t seen much attention to the impact of adoptive sibling bonds, in children’s literature or elsewhere. Whereas the former exclusion amounts to simplification and erasure, the latter overlooks potential for familial bonds beyond those with adoptive parents to nurture and sustain adoptees. Of course, not every adoptee has siblings who will grow up sharing their experiences, but I am so grateful mine do because the nurture I provide them is enriched by that which they give one another — particularly as children of color with white parents.

This knowledge was reinforced the day I witnessed my daughters’ pretend-play shift into a conversation in which they continued to take care of one another in their talk about adoption and sisterhood. In my picture book inspired by that interaction, and in my family’s day-to-day life, I’m not much interested in nature vs. nurture debates that form a hierarchy placing one above the other. My children need to have their birth families’ lives respected and honored, and they also need affirmation of their own rightful places in our family. These needs are interdependent, and they are met, in part, through the very real bonds they’ve formed as siblings as they live out the stories of their lives.

The author’s two daughters sign books along with illustrator Nicole Tadgell and the author, 2016.

Megan Dowd Lambert