Reading Picture Books With Children Through A Race-Conscious Lens

In this hour-long conversation, featured guests Sarah Hannah Gómez and Megan Dowd Lambert share expertise and experience on 1) how to guide children to and through picture books with positive racial representations; and 2) how to support children in resisting or reading against problematic, racist content. They also take questions and comments. Access the video, resources and slides above. An edited transcript to the whole conversation follows. The Q & A starts towards the end of the transcript. And at the very end find a resource filled addendum to the Q & A, our guests' short responses to questions we ran out of time to answer live. Enjoy!

EmbraceRace: Welcome to this month's community conversation. We're thrilled to introduce you two our two guests. After a brief intro they will present for about 20 minutes and then we'll take questions.

Megan Dowd Lambert is a reviewer and contributor to the Horn Book and Kirkus Reviews and a Senior Lecturer in Children's Literature at Simmons College. Her books for children and adults include A Crow of His Own, (a 2016 Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Honor book), Real Sisters Pretend and Reading Picture Books with Children, which introduces her inquiry-based, dialogic Whole Book Approach to story time. All of Megan's work in children's literature is informed by her experience as a mother of seven children, ages 0 to 20, in a multiracial, queer, adoptive, blended family. Megan is also a friend. Welcome, Megan.

Sarah Hannah Gómez is a doctoral student in children's and adolescent literature at the University of Arizona. She holds a M.A. in children's literature and M.S. in library science from Simmons College - where she and Megan met - and a B.A. in creative writing from the University of Arizona. Formerly a member of We Need Diverse Books and the school librarian. She now teaches undergraduate courses at the University of Arizona and works as a freelance writer and editor.

Welcome, Hannah. And Hannah will start us off.

Sarah Hannah Gómez: Hello! I'm going to talk about choosing your books wisely and looking over your whole pool of books - whether that's your library or your personal collection - and ways to think about how you're choosing books. Then Megan is going to go into the Whole Book Approach and how you can use books once you've chosen them.

First, a list of a bazillion resources that we like to use. Some of them are individual people who write really good book reviews from various perspectives. There are also a few quick guides to how you can think about books and how you can analyze them.

Draw on Expert Resources

Here are some of our favorite expert resources for finding and assessing diverse children’s literature:

•We Need Diverse Books & the Our Story App

•See What We See: Social Justice Books, A Teaching for Change Project

•AICL, published by Nambe Pueblo scholar Dr. Debbie Reese

•LatinxsinKidLit

•Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop’s Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors framework

•“10 Quick Ways to Analyze Children’s Books for Racism and Sexism” by Louise Derman-Sparks

•Reading While White

•We Stories

•CCBC at UW-Madison, with annual children’s book publishing diversity statistics

Sarah Hannah Gómez: And then the top link is We Need Diverse Books which I'm sure a lot of people have heard of. It started as a hash tag and now it's a full fledged 501c3 with about 20 projects or programs going. They recently launched the Our Story App which is the project I spearheaded while I was a member of WNDB. That is a really great resource. It's an app but you can actually use it on your computer, too. It allows you to look for books either because you specifically are looking for some kind of diverse experience which goes beyond race and also includes religion, disability, gender, and on and on. Or you can look for, you know, you really want mysteries involving ghosts and you can search that way and it just happens that all of your results will be diverse books. So that resource and many other here for you.

Now, I want to talk about, again whether it's a library or a bookstore or just your personal collection, how to conduct a diversity audit and why that's important to do.

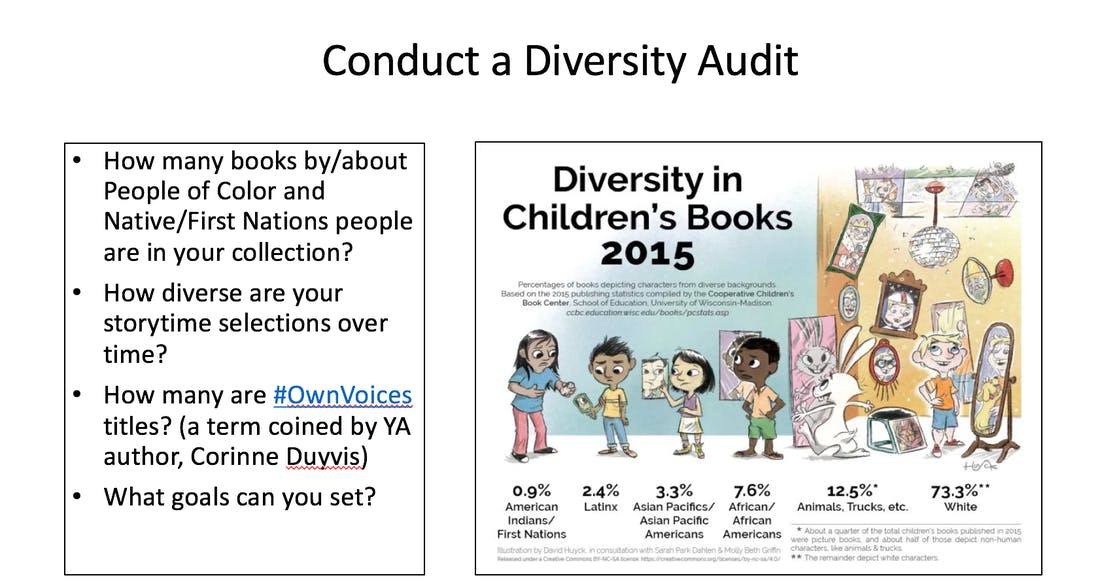

Sarah Hannah Gómez: So you can see on the right we have this great image reflecting the 2015 stats out out by the Cooperative Children's Book Center, stats on essentially all the children's books published in the U.S. that year. They might be missing a few, but for the most part it's every single book published by a publisher, as opposed to a self-publisher, that came out that year. And they go through and check, for example, how many books are about x race.

They also note which books are by creators who come from that group which we call #OwnVoices, a hashtag that Corinne Duyvis came up with. These numbers that you're seeing right now are just books "about" regardless of what background the creator has. So as you can see, it's only about 10 percent total that are about children who are not white, which is ... horrifying.

So that's why we think it's important for you to go through your collection and conduct an audit. There are very detailed ways of doing this but the major things you want to look at when you're going through your whole collection are ...

Sarah Hannah Gómez: First, look at how many books by or about People of Color and Native/First Nations people are in your collection as a whole. It's probably a lot easier to know whether they're "about" before you go through the "by," so starting with that is going to give you a good understanding of what your book collection looks like.

And then look through that and think, how diverse are your storytime selections? Which books are you pulling over and over again because you really love them, and which books are you not choosing even if they happen to fit the diverse umbrella? Then you can look at how many of those books are "own voices," although that tends to take a lot more research so don't suggest doing that in your first audit or beginning steps.

And then think about the goals you can set. In a class that I TA'd when people were doing this type of audit, a lot of people looked at census data, either national census or looking at their community, and saying, I have 50 percent Latinos in my neighborhood, so that's what I want my collection to reflect or as close to that as possible. So you might have various goals but set some goals so that you know what you're looking for.

So some questions I like to ask myself because, even those of us who feel like, you know, I'm a social justice warrior and who like to think we're reading diversely, often aren't. Sometimes I do an audit of my reading and I'm not doing so well! So even the most conscientious of us need to ask these questions.

Sarah Hannah Gómez: Does this book look like the community I live in? So some people might say, I live in a really heavily whatever group community and my books don't look like that and that's a problem. Or I live in a really homogenous community. And my collection does look like my community and maybe I would like more books that don't look like my community.

A good question to ask along those lines: do the people in this book look like me? And that's kind of going to be the same. Like me, from majority group or minority group. And what am I seeing in these books.

I think the big one that we're not asking enough even though diversity is more and more of a goal for people, is: if I were a member of the community or culture represented in this book would I be hurt by the way it's depicted? From something that's really aggressively hurtful, like blackface, to things like, hey, I don't talk like that? Or that's not a term that my group uses and yet it's being presented as a slang term we use every day? So it can be a micro-aggression or something more egregious. Think about, if this were me, is this the book I would want to give to someone who doesn't know me to get to know me?

Sarah Hannah Gómez: Are any parts of this book problematic? If so, do I have the words to explain to a child what is troubling about it and/or do I know how to phrase a question to guide children into thinking critically about it? I think we all have a book we love that probably has something in it that's not great. So just thinking, if I read this and a child notices the same thing that I've maybe secretly noticed about this book, do I know how to tease out a conversation so that I'm not just going, "Yep it's racist. Moving on ..."? I think we're all prone to doing that because we can identify something but to actually express it can be a lot harder.

And then the last one is, do I have an argument or some kind of defense for why I'm reading this book aloud or why I'm keeping it in my collection, in my bookstore? Do I have my elevator pitch for why this is a book worth being read?

So "problematic" is one of those terms that has been killed by both sides of the political spectrum, either from overuse or from being called snowflakes because we use the word too much. Or are you using it too liberally or whatever. But I'm using problematic to describe a book that has something in it that could be iffy or offensive or something that's worth problemitizing. So something that we can take issue with or unpack a little bit.

Are there some stereotypes in the art or in the text? Are the bare bones of the plot or the essence of the characters similar to a book I already know is offensive or a problem? Is there outdated language that describes racial or ethnic minorities? And then ultimately, people have differing opinions on this, once you've unpacked a book, does the good stuff about it outweigh the bad? Is there one word but otherwise this book does a really great job in a particular area? Does one thing outweigh the other? And that's kind of a personal choice but also one that is hopefully informed by some of the resources that we showed you before.

If I'm not from a group, I'm not the person who should ultimately be saying this is definitely not offensive enough, but using those tools to think about whether it's worth keeping. If you only see one problem in a book and you have the words to work with a child about you know unpacking that problem, is it may be worth keeping because 99 percent of the book is good?

My favorite quote about this is: "We can disagree and still love each other. Unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist" [James Baldwin]. So especially in today's political climate, I see on people's Facebook, arguing with a cousin or something, saying, well we're just going to have to agree to disagree. I just find that not true! We can agree to disagree about whether mushrooms on pizza are good. But if your disagreement is about the fact that this book says that you are less important as a person than a white person, but we'll just agree to disagree? No! No, it's not okay that you think that. I like to use that as a kind of guiding post when I'm considering whether this book is mostly good or mostly bad.

Megan Dowd Lambert: Now we're going to transition. Hannah is going to come back and have more to contribute. But now what I wanted to talk about is, OK, so you've drawn on these resources to find and assess diverse books. Now what do you do with them?

Megan Dowd Lambert: So my work is really grounded in leading storytimes and in leading a specific kind of storytime. I like to lead co-constructive storytimes, which is kind of a fancy way of saying reading with children as opposed to reading to children or another way to frame this storytime as book discussion versus story time as performance.

So when I'm thinking about engaging kids in critical discussions about representations of race or about anything, I really want to think about how do center kids? And how do I bring them into the discussion. As opposed to thinking, OK kids I'm going to read this book and it's going to be a performance and you'll sit and passively absorb it. So if there's one shift I want you to make in your minds as we go into this work a little more deeply tonight, it's that shift of reading with children as opposed to reading to children of story time as book discussion as opposed to story time as performance. Because I think that ends up democratizing storytime in a sense, it ends up shifting the balance of power so that the adult is removing themselves from leading all the thought that's going on. And instead, the adult is facilitating the children's involvement and what the children have to say.

Megan Dowd Lambert: So this is a little slide about my book about this approach, The Whole Book Approach, which I created in association with the Eric Carle Museum. I developed the Whole Book Approach as a way of getting kids to talk about art and design. But what I find was that by welcoming them to do so, and by making it clear to them that their thoughts and ideas about art and design were important to me, lots of other things that were important to them started to bubble to the surface. Including some really rich discussions about characterization, which of course is often informed by race and other places of social location.

This is a picture of me with five of my kids. I am a mother of some children of color and some white kids, some adopted some biological to me. We have a really big range of personal experience in our one family. And a lot of my experience as a mother has really informed my experience working with kids in storytime contexts. So I've listed some Whole Book Approach techniques, and my book has a whole chapter about this at the end.

Megan Dowd Lambert: But what I want to emphasize tonight is yes that shift of reading with children but also the value of asking open-ended questions.

And I say here, under the Whole Book Approach, that I'm asking open-ended questions with embedded book design and production terminology which is true. But in addition to that, we can think about how these questions that engage visual literacy can lead us toward embracing race at storytime, toward asking open-ended questions that get kids thinking and talking about how picture books represent race through their art and text.

So here are some initial questions that might be useful to you. Just to start to get used to this open ended questioning technique during reading, whether you're reading at home or you're reading in a library or a school. These are inspired by Visual Thinking Strategies. The first question ...

Megan Dowd Lambert: What do you see happening in this picture? Or you could extend that to this jacket art or these endpapers, whatever you're talking about with a picture book. What do you see happening here? That grounds your group, or the one child you're reading with, in the visual.

The second question that you follow up with: what do you see that makes you say? That is asking for evidentiary thought which is the cornerstone of critical thinking. So if you can use those questions in concert with one another, you're meeting the child where they are, they're reading the pictures - young kids, kids who don't yet read text, read pictures - but then you're also asking them to back up what they say.

And this, when you're working with a group, allows you to engage lots of different perspectives because if everyone can have evidence for what they see then we can engage in dialogue as opposed to just spouting opinions off at one another and then defaulting to "oh, we'll just agree to disagree." No, no, no. We're not going to agree to disagree and we're not can engage in any false equivalencies either. We're really going to dig into a critical discussion, and your role as storytime leader, my role as storytime leader, is to facilitate that.

Megan Dowd Lambert: This last question here - what else can we find? - invites more. It says, let's dig deeper. We're not just going to sit with one response and say, OK, on we go. And again, there is a lot to facilitate with this. But what I found time and again is that the "leaning in" effect that's created by using these techniques really creates a cognitive and emotional investment in children, that they want to work together to build this meaning.

So how do we embrace race story time? A lot of the discussions that I would say embrace race in storytime in my experience have really bubbled up organically with a consideration of character. And I'm going to talk about some examples of that in just a moment. But I wanted to direct your attention to the work of a librarian who I saw speak at the ALA [American Library Association] annual convention this summer. Her name is Jessica Ann Bratt. And she's a library library manager in Grand Rapids. She has this Google doc which is up and available for anyone to look at. It's called "Talking about race story time" and I've linked it on this slide. We'll make sure it gets out to you in our resource list.

I pulled some of her key points here. They're paraphrased to fit on the slide. But she's really asking us to be direct and to be open and to be vulnerable, and to also make space for the children at storytime to be the same.

Megan Dowd Lambert: Her very first point, which I think is one that white people need to hear more than people of color, native, first nations people, is it's OK to point out racial differences in picture books. Lots of us white people we have been socialized to think that talking about race is impolite. And she wants us to disabuse ourselves of that notion right away. But then, all of the other points I think are really relevant and important for people no matter what race you are and what your experience is so that you can engage kids in talking about race at story time. So that's a resource I hope that you'll check out further.

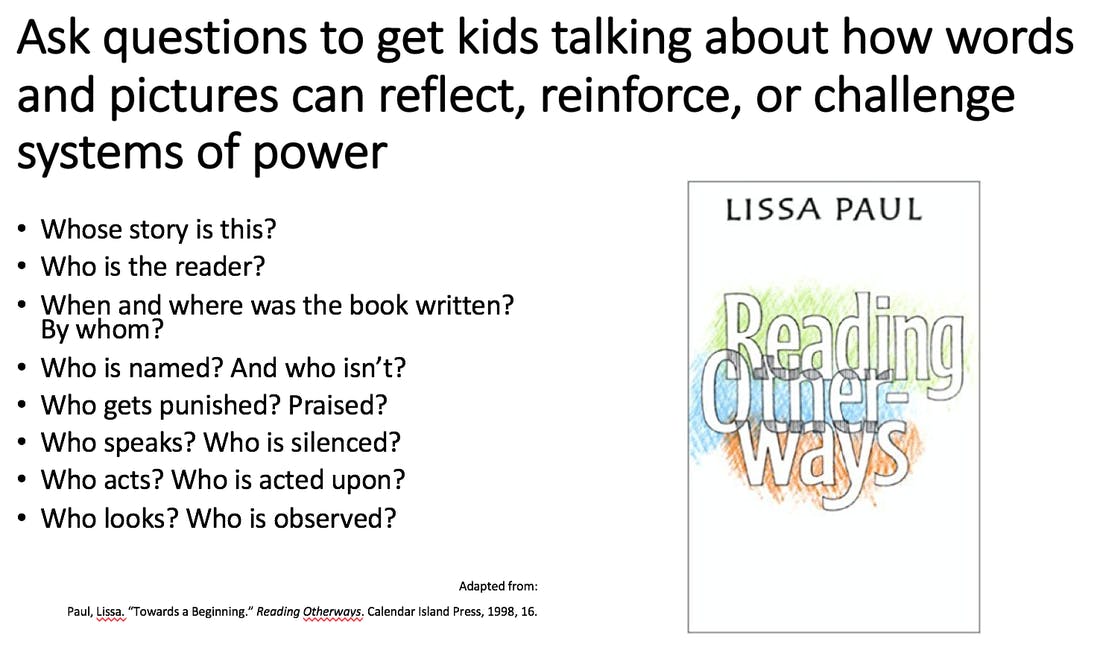

Megan Dowd Lambert: Some other questions I wanted to point you to come from a scholar named Lissa Paul who is a white Canadian scholar of children's literature. I use this text - Reading Other Ways - a lot in my own teaching. I love these questions that she offers us right at the beginning of her book because I think they really can prompt children to talk about how words and pictures can reflect or reinforce or even challenge systems of power. That first question - who's story is this? - is so important. Who is centered in the story versus who is marginalized? Who is the reader?In other words, who's the implied reader? When and where was the book written? By whom? Who is named and who isn't? Who gets punished or praised? Any of these questions that you can use to guide discussions about power dynamics can, in turn, guide your discussion about representations of race because, of course, our representations of race exist within power structures.

So I wanted to share a little bit just a taste of some of the stories of real kids who have engaged with picture books and embraced race in my storytime work with them.

Megan Dowd Lambert: The first story isn't from a storytime it's from reading with my own child. This is my son who is now 12 almost 13. He was 5 in this picture. And when I read Dave the Potter with him, I'd been on the Caldecott committee when it was awarded the honor, he was really powerfully moved by it and very distressed by it. We had talked a little bit about slavery in our day to day life and in our conversations as he grew up. He came home to our family when he was two. By the time he was five he was still trying to grapple with this part of our history. And he said things to me like, why didn't people who were enslaved just leave? Or, that's not fair that they weren't paid! And he he ended up getting a very deep emotional connection to this real person from history.

And as I was talking with him about this, I realized he wanted to touch the book. He wanted to engage with the book deeply. And I think part of the reason for that is that the art is unframed, and when art on the page is unframed it welcomes you in, you feel less like you are on the outside. And when I walked into his room after we had read it and I saw him putting his hands over Dave the Potter's hands as in this gatefold spread where the pot is being thrown, I was just so powerfully moved because this discussion that we'd had about art and design and about history had really forged a deep personal connection for Stevie.

This next slide is a book I was reading with a second grade classroom.

Megan Dowd Lambert: And I used questions like, what do you see happening in this jacket art, to get kids to engage with this powerful portrait of Dr. King. And then I moved to the end papers which look like these stained glass windows. And I ask kids what clues to these papers give you about the book? And they said things like oh the different colors look almost like different skin tones and they're all united. Or church is a place of peace and it's a place of hope and that's what Dr. King was preaching. And then I heard a child say, well I see prison bars. And all of a sudden our whole discussion shifted and instead of only talking about hope and peace and justice we started to talk about struggle and injustice. We started to talk about how Dr. King was imprisoned for his activist work because he was challenging unjust laws. And that was a moment that I'll never forget because I wasn't thinking about that possibility when I looked at these end papers. But by centering the child's response we were able to bring that perspective in.

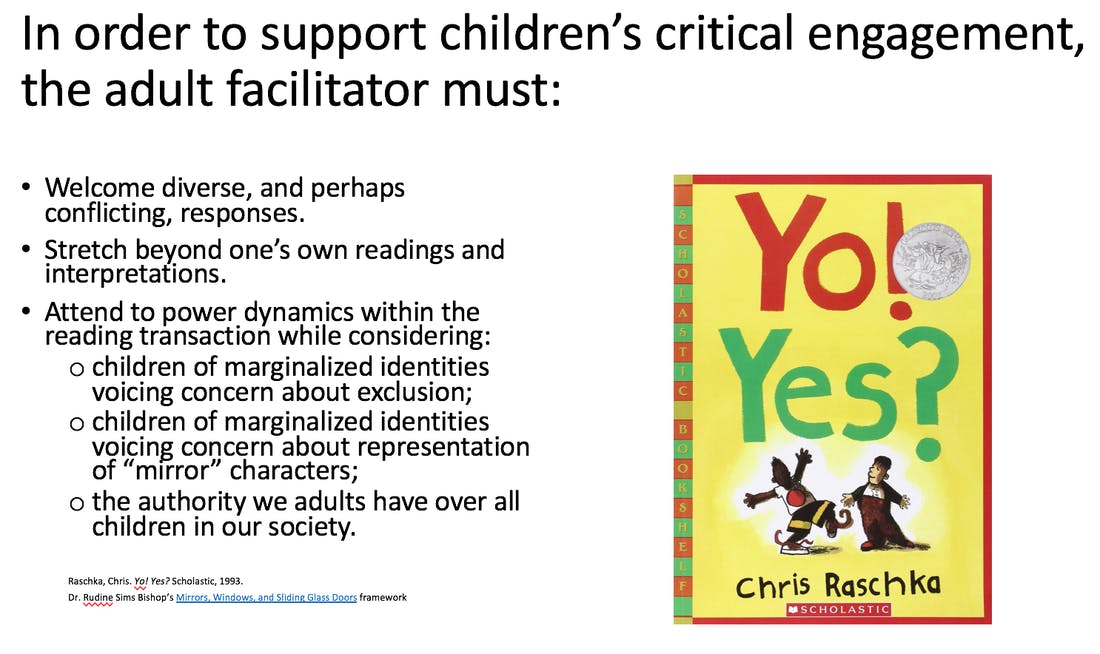

And then the last story I want to share is about a book. Yo! Yes? By Chris Rashtra. And I want to use it as kind of a reminder about what we need to do to make this whole space for kids when they are reading race and in books. I'd read this book many, many times, about a boy with dark skin and boy with light skin - I read them as black and white - who aren't friends and then they become friends. And I'd read a little write-up that the author Jacqueline Woodson had written about this book in the Horn Book Magazine that said this is the book she would put in the hands of a child 100 years from now because it's about reaching out across difference and that was the spirit in which I read it with a group. I think they were second graders as well.

And I got to this page and I read "Yo. Yes?" And a little girl in the class. It was a very homogeneous class. All white except for this one little girl who was black. She stopped me and she said, I don't like how he talks. And I said, Well tell me more about that. Why don't you like how he talks? And she said, he's really rude. You don't just say "yo!" to someone, you say, "hello, my name is ..." And I said OK, well tell me more about this picture? What else do you see happening here? Again going to those open-ended questions to hold space for her.

Now I'm not going to tell her what Jacqueline Woodson said about this book. And I'm not going to tell her what I think about this. She started to unpack this character and what she ended up saying, and her classmates joined her, is that the black child and the white child are constructed basically as a false racial binary opposition. Now that wasn't the language they used. But they said the black kid is wearing the basketball on his shirt and not all black kids play basketball. And the white kid has this buttoned up shirt and the black kid wears all sporty clothes and the white kid looks like a nerd.

Megan Dowd Lambert: And they started to unpack this and resist the characterization. I didn't go back and say, well, my black kid thinks this is the flag of Japan, right? My role isn't to push back against a child's reading, particularly a child who was the only child of color in the classroom, to shut her down. My job is to hold space for her.

So these guidelines over here on the side are things that I want us to all keep in mind no matter if it's storytime or if we're in a classroom or if we're just listening to one another in conversations about race. To try to welcome diverse and perhaps conflicting responses to stretch beyond your own reading. That's something I have to do all the time and try to be humble about that. I might have read this book a hundred times but a point of reading is to see what other people think at storytime or in a class. And also to attend to power dynamics within the reading transaction to make space for kids particularly those of marginalized identities to take risks and to not be shut down.

And the one the one thing that I'll add to that is, particularly as the adult who's leading the storytime or in the teacher role, the damage that you could do to a child, by saying, for example, "That's not what that is. That's not a basketball on his shirt!" What you're telling that child is you're reading doesn't matter as much as my reading does. And when you add a racialized dynamic to that I think you're really creating harm. And so holding space is something I think about a lot.

I don't remember who said it, but I saw a tweet once. That was the acronym W.A.I.T. for, "why am I talking?" And I think of that WAIT acronym a lot when I'm entering into discussions that I'm facilitating in particular. Why am I talking? I want to get you talking, you children at storytime talking. And if I'm talking to be the conduit through which you received the book terrific. If I'm talking to facilitate your experience fantastic. But if I'm talking to hear myself talk, not so good.

So with that I will stop talking because I think we're going to move into some questions.

EmbraceRace Community Q&A

EmbraceRace: So you thank you both. Yeah let's jump into questions. Let me start with one. When you were describing the Whole Book Approach, what I pictured was three characters interacting when you're using this approach - the book, the adult reader, let's say, and the child, and of course more characters if there are more children. And I love that because I think we so often give primacy to the book, right? You just get a great book and then our work is done. And you're saying. no. There's an interaction, there are at least two characters who have a lot to say about how that interaction goes. I really love that.

You talk about opening space for children. Certainly not valuing one's own interpretation or understanding above that of a child. I want to ask you about sort of the flip side of that. You can certainly read books in which there is context that the child may not understand and, possibly, this Socratic approach of asking questions may not actually yield all the information. So I love what you're describing.

And I can imagine some parents and teachers and librarians and others running into quite a bit of a sticky spot if the child isn't supplying all the information that they feel necessary to get at what the book is about. So what do you say to that?

Megan Dowd Lambert: It makes me think of that distinction between teaching and education. That education from the Latin educare means to draw out, say okay child where are you and I'm going to draw something from you. And teaching is I've something to convey to you and I'm teaching you. An educator at the Carle [Eric Carle Museum of the Picture Book] who I worked with for years use to always make that distinction. And I think it's a balancing act. Do I have things that I want to teach people? Sure, yeah. But do I think it's as important if not more so to bring the child in? Yes.

The other thing is, usually, you're not going to read a picture book once. And so if your first time reading it you don't get to everything that you think or you hope you want to get out of that book, read it again. And that's true in classrooms and libraries as well, to some degree. It's certainly true at home where you know you re-read books constantly, or at least we do in my house. Would you add anything to that Hannah?

Sarah Hannah Gómez: This is something I struggled with. This was the first semester that I taught children's literature - last year I taught YA (young adult fiction] and it was a very different context - and I did some storytimes with my 21 year old students. I was like I'm going to read this book. And I really love this book. And there's also this one problematic bit. And I'm just going to wait for that person to call it out. But they just kind of clapped after I was done reading and I was like, what did you think? And they said, that was nice. And I was like trying to get them to a place and I couldn't get them there naturally. And I think it was because I hadn't set them up with your method, Megan, and had just read the whole book all the way through instead of stopping here and there to say, what do we see that's going on? Is there anything anyone wants to point out? And I think reading slowly is something I'm not good at but I see the value in it a lot.

EmbraceRace: I think many of us are used to, when children in our lives are very young, we do typically treat them like a passive audience. We are performing for them and they're a passive audience. And so, certainly the idea of pulling in even the youngest children who, as you say, can read pictures if not words, is super appealing. But even the person who subscribes to that might be tempted to think oh, but by the time the child is 9 or 10 or 12 and that child is able to consume the book on her own or his own, can't we strike the balance in a slightly different place?

Megan Dowd Lambert: I think what we want to do, or what I want to do, is give kids the tools, not only to read books, but also to read against books. So that it's not just that you're absorbing things, but that you're meeting the book and you're creating meaning in that space between yourself and the book because that's where critical engagement comes in. Like that child who was reading the characterization in Yo! Yes? who said, "I don't like how he talks." That was a critical appraisal. And by critical I don't just mean negative. I mean, I have an opinion about this and I'm going to reason my way through this opinion. So it's not simply telling kids what to think. Though there are some instances where I would absolutely say, yes, we're going to drive home a message. It's also showing them how to think, giving them the tools to think critically and to resist texts in addition to absorbing them.

EmbraceRace: There are a lot of questions streaming in so let's go to those, and there are a lot that came in early as well. Yesha says, What do you do if you're trying to elicit a response about a book from a child and the child keeps saying "I don't know" and gets frustrated that you're not telling them what's happening?

Megan Dowd Lambert: Or you get the response. Can't you just read the book? I was just joking today, my husband was asking our 2-year-old about the endpapers in a book and he just kept saying no no no and wanting to turn the page. I was like, Oh, Jesse hates the Whole Book Approach - great. But he doesn't hate the Whole Book Approach, he just wanted something different in that moment.

And so I'm not saying this is the way to read to every kid every time you open a picture book. I mean it's probably not the best bedtime technique if you're trying to get the kids to bed quickly at the end of the day. I'm just saying to approach reading with children with intention. Are you saying, right now, this is where I really want to have a dialogue. Or right now, this is where I'm going to be entertaining and fun. Or right now, we're winding down. Just be intentional about your approach. Add these tools to your toolkit and the child who's saying, I don't know or getting frustrated, don't push it.

I have a whole chapter in my book that's called the picture book playground which is drawn from the idea of looking at art as cognitive play that we're making meaning. And so if you keep it playful and you keep the child truly centered, that's when you'll have success in terms of creating conversation. If you make it seem like a test or like you're explaining a joke or something like that, yeah it's going to flop. Absolutely.

And the other key key piece is not only to be intentional for yourself, but to let your expectations be known, particularly if you're working in a school or library. Say, "I want to read this book but I really want to hear your ideas." Because sometimes kids are so used to being shut down - zip your lips and quiet hands and quiet bodies and all that - that they won't feel empowered or entitled to speak up. But if you say, "I really want to hear what you have to say," or "I've got some real questions about this book and I bet you can help me answer them." Make it an invitation. They might reject it and say, nah, I just want you to read to me tonight. OK, so read to them but have the expectations there.

EmbraceRace: Let's go to Emily, who doesn't exactly write a question but recently had a dilemma, which will be familiar to you I'm sure. "We recently accidentally encountered highly offensive racial depictions in the Dr. Seuss book If I Ran the Zoo. Our daughter greatly resisted talking about the racial elements of it. She just wanted to read the book and have fun. We really struggled with that."

So I'd love to hear your response to that. But one of the things that gets that is this question. Are there books that are off limits? Or is the presumption that we can engage most or any more or less otherwise age-appropriate book with our children through this approach?

Sarah Hannah Gómez Yes and no, as far as, are there books totally off limits. I'm claiming some of that is yes totally off limits until I've already had other conversations with my kids so that they've had precursors to that conversation. And you should have already been using the Whole Book Approach before using it with challenging content so they're used to this kind of inquiry. And don't don't pick the one that you're already struggling with, which obviously requires traveling back in time and reading the book before your child so that you're prepared for stuff.

EmbraceRace: The implication of the Whole Book Approach is that really we should try to have the child sort of set the table for the reading, right? Does that mean in this specific case of Emily's daughter and If I Ran the Zoo, that if the child doesn't want to engage the racial elements and the parents questions don't get her to do that, but perhaps wants to engage some other elements - is that OK?

Megan Dowd Lambert: The way that I think of it is that children's books are a form of socialization and they are a form of media. So they are reflecting culture but they're also building it. So if we have kids encountering racist content and we don't provide resistance or we don't provide context, we don't provide supports for kids who might be personally harmed by absorbing that, we're letting that happen.

And so in that instance, where the child doesn't want to engage around it and where you weren't anticipating it, I think the parent voicing concern and saying, "Wow, that picture really upsets me. I don't like that picture." That sends a clear message. Now having a great big conversation about it if the child is resistant could end up shutting down communication down the road. So personally, I might back off, but I would still voice that.

It makes me think of when my son who's now 20 when he was in fifth grade, I think it was fifth grade. Lots of kids were reading Tintin books and it was a real part of the social currency in this classroom. They were playing it outside they were reading them and he brought some home from the library. And I was like, "Oh really? You're going to read these? I don't like how these books treat brown people at all." He's biracial, half-Jamaican, half-white. And he was like. "Are you not going to let me read these books?"

And I said, "Well I'm not going to not let you read them but I'm good at telling you I object. I do not like how these books treat people." And so he was like, "Fine." And he went off and read them and then he came back to me. I can't remember how long later, but he said, "You know what, you were totally right. These books are insulting." And he went through and like picked apart the parts that he found insulting, when he was ready.

Now part of the reason I made that decision is I'm this white mother telling my black kid I don't like these books. I don't want you to absorb it. I don't like how it's perpetuating things but I also didn't want him to be the black kid in the class who wasn't allowed to read these books that all these other white kids were reading. I wanted him armed against those books and I didn't want him to be the odd ball out or to feel othered in some way.

Now, if it was one of my white children - my white children are two months and two years right now - but down the road if it was them, I would probably hold their feet to the fire a lot more around that. So it depends a lot on your place of social location and the relationship that you're engaging, I think.

EmbraceRace: And that brings up a good question that lots of people are asking. Lots of people, in regards to reading about race with children or reading race with children, really want a booklist. I know that you don't love that question and I wonder why you think you get it a lot and why you don't like it?

Sarah Hannah Gómez: We shouldn't be looking for diverse books, we should be looking for good books that happen to be diverse because we should just be trying to read diversely. So the framing of that question doesn't get at the issue of why we have to ask this question in the first place if all we're doing is saying, for example, give me your top three Chinese American books. I think just looking for book reviews or book bloggers like the blogs we mentioned earlier. There are some that are specifically about Latinos in Kid Lit, for example, but they're writing about the books they think are good and getting a full review of them is going to mean so much more and give you so much more information than book lists in general. Yeah. So a few different reasons I don't like that question.

Megan Dowd Lambert: When people ask me for booklists, I think of the bibliotherapeutic approach to parenting sometimes. Like, oh my child's pet just died, I'll buy all the books about pets that died or get them out at the library or whatever. And it's like throw a book at the issue. I want to be intentional about reading race in picture books no matter what book I'm reading. I don't want to say these are my 10 best books about race for kids. I want to say, maybe it never occurred to you you know to read "School's First Day of School" with a race-conscious lens but you could. Even though the main character is a building you still could do a lot with that book. The other reason I resist lists is that I want people to use their librarians as resources and to go to librarians and say, you know, I'm looking for really strong books to read with my kid just to engage in conversation. Certainly, we want thematic lists sometimes. But I think it's more than just getting the books, it's about the conversations you have through those books when you meet in those pages and you have those conversations.

Sarah Hannah Gómez: This time of year I'm definitely the book concierge to people who looking for books and then I love giving lists. But that's because they specifically told me, I have a 13 year old boy who loves baseball, he loves mysteries and ... he read this book before and hates it. So I have like a specific lens but the lens is not black people. It's this particular kid needs a book that will speak to him.

Megan Dowd Lambert: It's reader's advisory is what you're describing, the work of a librarian.

EmbraceRace: Let's try to squeeze in one last question. You showed the graphic earlier, Hannah, showing that in 2015 there are as many animal characters or inanimate objects as kids of color in picture books.

Sarah Hannah Gómez: Oh no, there more bunny rabbits and cars than children of color combined.

EmbraceRace: Oh, even better. The question is, can we talk about books with animals as human characters/protagonists - when that counts toward a diverse library and when it doesn't?

Sarah Hannah Gómez: I would suggest that everyone, if you're not familiar with the term "coding" to look that up. But it's all about how race is coded in things that aren't racialized, so think of Dumbo and the crows. How do we know those crows are black? Because those crows are totally black. Is it the way they're talking? Is that the way that they're drawn? Are they wearing clothes, if so, is that a particular type? So looking at other cues, whether it's the food they're eating or the language they're using. I'd say if it really points you to - oh I know what race they are - it means that they're coded as not-white, and if you don't know they're coded as white, is a general rule of thumb. But it's so complicated. We could say so much.

Megan Dowd Lambert: I've noticed that we get that kind of coding particularly when we want distance from subject matter that it says, OK we're going to tell this whole story but at a distance. It's not going to have human characters, but it's going to have human-like characters. And I noticed this particularly around issues of sexuality and gender in children's books. I'm not knocking the books - I love many of them. I'm kind of knocking the industry or the culture that says, if we're going to talk about non-binary gender, it's going to be worms in Worm Loves Worm. Or if we're going to talk about gay parenting, it's going to be penguins with Tango Makes Three. Not that there aren't other books that do these things too, but the books that get the big marketing keep certain topics at a distance.

And I think the same kind of thing sometimes happens around race as well or where sometimes you get animals stand-ins for humans and it kind of makes me scratch my head. So all these Zen books, the Jon Muth books with the panda named Stillwater. Is the panda supposed to be an Asian person who's like telling these white kids about Zen Buddhism? And how do we feel about that, that we have a panda who's doing this instead of an Asian person? I guess you can tell how I feel about this. I feel not so great about that. And I think that those kinds of coding - racial coding happens all the time in children's literature, especially when we want that distance from subject matter.

EmbraceRace: Yeah and so many of us, especially if you are raising kids of color like we are, in trying to not have a mostly white bookshop shelf, you end up having a mostly animal bookshelf. And then it's all coded anyway. Argh!

Megan Dowd Lambert: Yeah. Or you get - one thing that we didn't show stats that the Cooperative Children's Book Center have been tracking is that we've seen very recently a real uptick in the number of books about black characters but not by black people. I think it's still at like 3 percent in terms of authorship. And so that question of #OwnVoices is really an important one to keep asking. Not only of ourselves and our own libraries but of the marketplace. Who gets to tell whose stories is a crucial question. Who's controlling the narrative?

EmbraceRace: Well you guys our time is up. Thanks to Hannah and Megan for sharing so much personal and professional experience and expertise. We also appreciate everyone in the chat - we're learning a lot following that discussion, too. We'll see you every fourth Tuesday of the month, same time, with another EmbraceRace Community Conversation.

Addendum to Q&A

Responses to Questions We Didn't Have Time to Ask Live

Can we talk about books with animals-are-humans characters/protagonists and when that "counts" towards a diverse library and when it doesn't? By "animals-are-humans" I mean the books that are stories about humans, but the humans happen to be animals, like Arthur or the Berenstain Bears that have animals instead. I know more than a few adults who assume that these count as raceless or inclusive for the most part. I think it is more complicated than that.

Take a look at this essay about Anthony Browne’s work featuring anthropomorphic apes, which pushes against the idea of a “colorblind” reading of such characters and delves into the notion of racial coding that we discussed in the webinar:

Anthropomorphic Veneers in Voices in the Park: Questioning Master Narratives through a Socio-Historial Analysis of Images and Text

Megan was first introduced to this essay by librarian and critic Edi Campbell on her excellent blog Crazy Quilt Edi, where she posted about Browne’s work and interrogated other instances of anthropomorphic characters in picture books, stating, “I submit that anthropomorphic images are the quintessential dilemma of representation in children’s books.”

Can you recommend good sources of books for preschool-age children that depict multiple skin tones?

Julia Hakim Azzam offers many great resources about this in her article Books in the Home: “Mommy, Do I Have White Skin?”: Skin Color, Family, and Picture Books

While reading the "Little House" books, I loved the perspective of the child, especially when feeling naughty, and the can-do spirit of the Ingalls family. Is it OK to skip over racist portrayals of native Americans or should I skip the series entirely?

Hmmm. We actually think it’s impossible to “skip over racist portrayals” when reading the Little House series because of the foundational lies about settler colonialism that the books are built on. And in many books in the series (perhaps especially in the second title, Little House on the Prairie) you’d be forced to skip over a very substantial number of pages to avoid overtly racist content, while in that and other titles you’d have to skip over perhaps even more pages to avoid storytelling that erases Native people.

Take a look at this article: The Little House on the Prairie Was Built on Native American Land. Some suggest reading these books with a critical eye. Others choose to skip them altogether. Check out Sarah Hannah Gómez’s essay on this topic: Decolonizing Nostalgia: When Historical Fiction Betrays Readers of Color and Megan Dowd Lambert’s essay “Alongside, Not Despite: Talking about Race and Settler Colonialism in a Graduate Children’s Literature Course.” We also recommend Barbara Bader's essay: “How the Little House Gave Ground: The Beginnings of Multiculturalism in a New, Black Children's Literature.” The Horn Book Magazine, November–December 2002, 657–73.

Can you suggest a recommended reading list?

Although themed reading lists have their place, the best way to match a book with a reader is to talk to a librarian about what the child is already reading, what their interests are, what you’re looking for, etc. BUT in addition to their OurStory app, We Need Diverse Books also has a fabulous summer reading series. There's no central location for them, just posts on their tumblr. You can find them by conducting this Google search.

Take a look, too, at the We’re the People Summer Reading Lists site.

Here's a blog post Megan Dowd Lambert did to culminate a month of daily tweet threads about the Whole Book Approach. You don't have to have a Twitter account to click on the threads to see how she considered a range of diverse books as she tweeted about book illustration and design. This is a list of all 375 picture books she posted about that month. One day she hopes to do a diversity audit of all of the titles on the list.

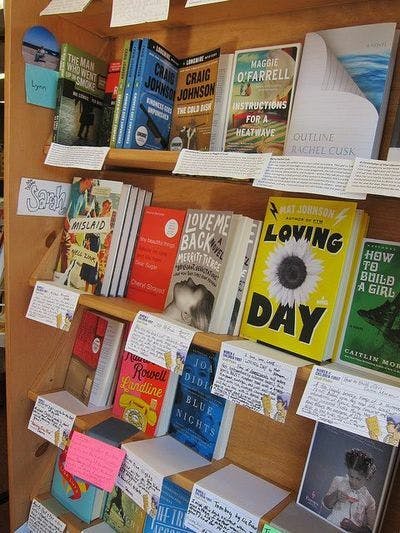

It's challenging to get multi-ethnic books to circulate despite keeping them on display. Any suggestions?

First, if you’re display theme is "diverse books," implicitly or explicitly, you won’t get much traction. Instead use genre themes "mysteries" or subject themes "baseball books," for example, and your circulation numbers should go up.

If that’s not the issue, try the "blind date with a book" strategy or use “shelf-talkers” to raise interest in good books that aren’t finding their readers.

If possible: suggestions for booksellers who interact w/adults buying books for children: strategies, phrases, etc to use when discussing children's books w/historical value & problematic content, or when asked for "multicultural" (aka nonwhite...) books?

When you’re asked for multicultural books, we recommend that you stress that they are BOOKS, not DIVERSE books. As far as problematic books, frame the conversation in a way that doesn't attack the questioner ("I can see what appeals to you about that book! The illustrations ARE beautiful") but immediately engages with the problematic content before the purchaser can just walk away with the book ("I read it a lot as a child, but as I grew up I realized that some of the pictures made me uncomfortable because..." "a friend of mine pointed out that some of the words used in this book are insensitive because...") -frame it as being a learner yourself - or, if you are a POC, describe how it hurts you (if comfortable doing that).

We Need Diverse Book’s booktalking kit will help. It includes their “diverse” book recommendations for various ages as well as their downloadable “shelftalkers.”

Additional Resources

- See What We See: Social Justice Books, A Teaching for Change Project

- “10 Quick Ways to Analyze Children’s Books for Racism and Sexism” by Louise Derman-Sparks

- Reading While White Blog

- We Stories

- CCBC at UW-Madison and its annual children’s book publishing stats

- AICL, published by Nambe Pueblo scholar, Dr. Debbie Reese

- LatinxinKidLit

- Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop’s Mirrors, Windows & Sliding Glass Doors framework

Sarah Hannah Gómez

Megan Dowd Lambert