Choosing Excellent Children's Books By And About American Indians

With special guest, Dr. Debbie Reese

How do you choose children’s books about Native peoples? Because most of us were socialized and educated to think of Native peoples in narrow and biased ways, we typically don't recognize how deeply flawed many of the books we choose are. Too many children's books present Native peoples exclusively as historical figures, for example, ignoring the presence and realities of the 500+ federally recognized Native Nations in the United States today. Too many present American Indians as "people of color," which they may or may not be, dismissing their defining attribute as people of sovereign nations.

Watch this Talking Kids and Race conversation with special guest, American Indians in Children's Literature founder Dr. Debbie Reese. Dr. Reese offers an opportunity to move beyond what you've been taught to a place where you're able to identify great books about Native peoples, the original people of the lands currently known as the United States of America.

Find the transcript (lightly edited for length and understanding), related resources and more about Debbie Reese below. Don't forget to check out about past and upcoming monthly Talking Race & Kids online conversations, too.

EmbraceRace: How did you come to this work? Give us a little back story.

Dr. Debbie Reese is tribally enrolled at Nambe Pueblo in northern New Mexico

Dr. Debbie Reese: I was a teacher in New Mexico. I was a teacher and then I became a mom. I quit teaching and all the books that were in my classroom library became my daughter's books and I started working more closely with the people at the Pueblo in our tribal nation on family literacy kinds of activities. So when I started thinking about grad school, I thought I’d study family literacy. So I moved to Illinois and started coursework with that in mind.

But there was a mascot at the University of Illinois, Chief Illiniwek, that would end up changing what I was doing. It's a stereotypical mascot and I was trying to understand, what is this thing? And why do people think it's so wonderful when it was clearly not wonderful at all? So I shifted from thinking about family literacy to thinking about how and what are people seeing in their books that make them think this is a good image. This stereotypical image of a Native person. It's not even really a Native person. It's a fiction of who we are.

So it was kind of a culture shock to come here and think, wow, these people really don't know a whole lot about why stereotypical imagery is bad for all of us. So I started looking at images of Native people in children's books. That became the work that I do pretty much 24/7, because books are everywhere. Books really matter to parents. Parents read to kids at bedtime and the books that they're choosing to read to their kids at bedtime or in the morning, at breakfast, wherever and whenever they choose to read really matter because these are people that love their children giving their children information in the books that they're using with them. And so I really felt that I could make an intervention in what people know about Native people by way of talking about the books that they use with their kids.

EmbraceRace: When you say 24/7, I believe you as a follower of yours on Twitter (@debreese)! I wonder if you could tell us a little bit more about what's at stake because in addition to helping people find excellent books that are true to the people they're trying to represent, you're also known as a #DiversityJedi [a group of inclusive children's literature advocates using Twitter to push kidlit publishers to do better - origin story here]. You're huge on Native Twitter for also speaking out on all kinds of things that happen every day and that aren't really directly about children's books. Can you speak about sort of your broad activism?

Dr. Debbie Reese: Yeah, I hit on something sometime last year or the year before that seemed to resonate with a lot of people. The idea was that in most of the schools in the United States, there is a month for a particular group. So for Native people that's November - a terrible month for us to be in because that's Thanksgiving and that feeds into long-ago, far-away stereotypes about us - not good content to be associated with. And so for a Native child, that's kind of when the Native content appears in the school curriculum. So that child only counts in the school curriculum in November.

Meanwhile non-Native children, white children especially, are affirmed in their existence as kids who play in the neighborhood, who go swimming, who go camping, do all the things that kids do, their life is affirmed all year long wherever they go and whatever they do in books and movies, in toy products at the store. They will find some semblance of their existence as a person of the present mirrored or reflected back to them. And that's not the case for Native people.

We are Native people all year long, every day. That isn't something that happens only one day or one month of the year. And so it is a 24/7 experience. Every time I open my eyes in the morning, what I see on the news or on Twitter, it all impacts the work that I do because, I think, okay here is an opportunity to talk about what I'm getting at. That we see these things all the time and our children see these things all the time and we need to make what they see reflect their lives in a good way in the same way that non-Native children have that experience all the time.

American Indians in Children's Literature Best Books can be found here: https://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/2018/12/aicls-best-books-of-2018.html

EmbraceRace: When you talk about representation of Natives in books and in children's books in particular, I know there are a number of dimensions. Some of the most obvious … Are Native characters in the books at all? Who's writing the books? How are Native peoples being represented? Stereotypically, with more nuance? What about variation across tribal nations? All those sorts of things. When you look at the more holistic picture of representation of Natives, between 2006, when you started American Indians in Children's Literature, and now, these last 13 years. What do the trends look like to you?

Dr. Debbie Reese: Well now more than before, because of my blog and because I am quite active, I do have attention from the publishing industry. I hear things like, "Well, we don't want Debbie to see this" [laughs] or things like that because they know I will say something. So I think there are some changes that are happening. There is a sense of fear. There's also a lot of white writers say, "Well do you mean I can't write about that stuff?” To which I say, you can write about it but if you don't do it in a good way or if you have factual errors or stereotypes, I'm going to say something about that. So using my platforms to try to get this information out there has, I think, made some differences.

It would be hard to quantify because there are more representations of Native people in children's books and in chapter books and young adult novels I think than there are of anybody, but they're mostly misrepresentations and I can't possibly see them all because there are so many. So we have little things like when someone, a young adult novelist, will have “low man on the totem pole” in their book and then some will say, "Have you seen what Debbie said about that?" And they will go look and go and be embarrassed and grateful, some grateful, to have the information and then they will write to the editor and say, "Next time we print this, can we take that out?" So I know about some of that because they tell me. But I think it happens a lot more than I know. And I think that it doesn't happen, too.

So sometimes it feels like myself and the other #DiversityJedi have a huge impact. But we are just a little tiny group trying to effect change. And there has been change. I think there are more Native writers getting published now than there were in 2006. They are still being published mostly by small publishers, by tiny publishers. And what that means is that we can have all these wonderful books but all it takes is one Simon and Schuster [the publisher] book with problematic representations throughout to kind of erase, wipe out and obliterate all the good that 10 children's books from a small publisher can do. So these major publishers are doing a lot of damage. And that's where we really need to push very hard. And so I spend a lot time on that in particular.

EmbraceRace: You have been able to have impact in this kind of David and Goliath situation [vis a vis the big publishers] and I wonder if there are any lessons from that you'd like to share for other people who just think, "But they're so big! What can I do?" What do people not know that you would tell them about being a #DiversityJedi?

People tend to say things that are very well-meaning but that are off, like: "Thank you for your tireless work.” “You tirelessly work." I get really tired! [laughs] It's exhausting work. And I would like other people to do the work as well! When, for example, they thank me for sharing my perspective on what’s problematic about Little House on the Prairie, they can keep that info inside of themselves or they can share it. I really want them to share. I really would like to see people go to their bookstore and say, "Did you know this has stereotypes in it?" And, "I was going to buy this book. But you know, there are stereotypes in it and it's not good for my kid. It's not good for Native kids and I'm not going to buy it." And the outcome of an interaction like that between a customer and a sales representative or a clerk at the store is, there's little ripples that go from there. So that clerk is maybe going to make a report to the manager that they had a customer in there, they didn't like this book and why. So these little ripples of information that are going out. And I would really like to see more people do that.

What I'm talking about is stepping up and speaking up so that it doesn't fall on a few people, on a very tiny group of people. [laughs] We have to have way more people doing that and customers have a lot of power. I mean this country runs on that dollar. So using your dollars and your voice to share what you learned from my website or from writings or from other people is really important.

EmbraceRace: I find it effective to go in with a list to a library or a bookstore. The librarians in the children's library near us, we told them that you were going to be on and they're like, "Debbie Reese!" They have so many of the books that you recommend. So we were glad about that, although like you said, it's harder with the smaller publisher. They tend to not have those as readily.

Dr. Debbie Reese: Right. And one thing that I think people can do, too, is when they learn about a book from a small publisher, they can go to their library and ask for it. If the library doesn't have it then they will try to get it even though it's from a small publisher. But also maybe donating, seeing if your library will accept copies of books or funding to go towards small publishing books from small publishers. I think it's a lot of creative ways that people can try to get those books into the libraries.

EmbraceRace: Debbie, you started to touch on these but what criteria do you recommend for distinguishing the good from the bad when it comes to children’s books about Native people?

Dr. Debbie Reese: Well, one of the things that I ask people to think about is that we are people of the present day. So when you're looking for children's books about Native people, I'd like you to look for books by Native writers. There is no guarantee that a Native writer is going to do better in telling a story about his or her own tribal nation than a white person would. But it stands to reason that they likely will, especially if that's a part of where they grew up. So today we're calling that #OwnVoices. It's a hashtag #OwnVoices and I encourage people to get books by Native writers.

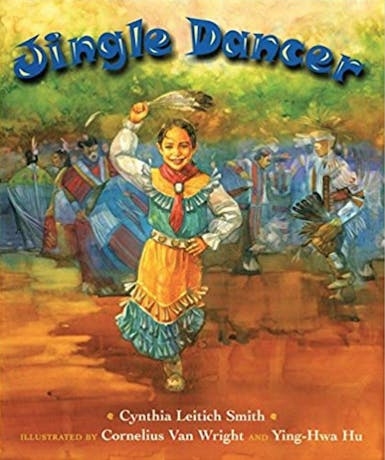

They can do a lot with that because not only do they have a book by a Native person, they can say this book is by Cynthia Leitich Smith. That's Jingle Dancer, and the use of that word "is" puts us right in the present day. Far too many children's books are long ago, far away, said in the past. So that's what we're pushing very hard against. Using #OwnVoices lets you push against that. So that's one thing - choosing Native writers because they're doing own voice stories.

Second, choose books that are tribally specific. Books by Native authors are more likely also to be tribally specific, and to name their nation - that's really important.

I've been using “nation.” And I realized we probably didn't talk about that enough at the beginning.

Native people were and are citizens or tribal members of nations that existed before the United States existed as a nation. There are words that people read in their textbooks when they’re little kids [that we should revisit]. [One such] word is "treaty." We as adults know what a treaty is. It's an agreement between heads of state. Well that was happening way back in the 1600's and the 1500's between European nations and Native nations. You don't make these kinds of agreements with "primitive people." You make them with intellectual heads of state. So the idea “treaty” really embodies is important for people to spend a bit of time thinking about because that gets lost in the overwhelming image …[a ubiquitous stereotype] of half-naked Indians running around in the forest, chasing and living with animals in a way that wipes out the whole possibility that we would have this thing called nationhood, sovereign nations. So we had societies that had trading networks with other nations. We had languages and stories and religions and ways of doing everything that people in any society does. So really need to hit on that nationhood status, that we were sovereign nations.

EmbraceRace: Well that brings us to something we were talking about a bit earlier about the particular situation of race and Native peoples. So, we're EmbraceRace and when we say race we mean something that's mostly used to divide and not something that's very logical. And we talk about people being racialized. So it can be a color of skin thing. It can be due to religion. It can be due to Native status. It can be because of the language you speak and oftentimes it's a combination. So I just wonder how do people get confused about race and nationhood?

Dr. Debbie Reese: Well my thinking about that is rooted in in graduate school and teaching in the college of education, going through the multicultural textbooks and articles and such not where if you think about it like a chart, and across the top of the chart you have different underrepresented groups. And generally speaking in the United States that is African-Americans, Asian-Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans. And then on the other grid axis you have like food, clothing, these kind of material aspects of who these people any people might be. And you can fill in those grids with those characteristics of those people, but there is no nationhood line in that grid. So that doesn't even get taught. And so that's a key piece of who we are.

Now there's all kinds of ways that we present in terms of what we look like. You're looking at me, and I have darker hair and have darker skin but there are Native people who don't have darker hair and darker skin and they are Native because what makes a Native person is not what you look like. It's about your nation and how your nation has determined who its citizens will be and that's different for all of the different nations that we were talking about earlier. When we opened you said over 500. That's over 500 different Nations, each of whom has their own way of determining who their citizens will be based on their history and their interactions with other nations. So you have some nations that are fairer in complexion and hair color and you have some that are not. You have some that are taller. There's a such a range of appearance that when we default to the idea that Native people have a culture of tepees and bows and arrows and dark skin and dark hair and high cheekbones we're really shrinking who we are as a people into a very narrow and stereotyped existence.

EmbraceRace: So there's no way to be half Nambe Pueblo, for example.

Dr. Debbie Reese: Is there a way to be half American?

EmbraceRace: Exactly.

Dr. Debbie Reese: Right. I think that's one way that we're pushing back on that. People say, "Well you're only 50 percent Native American." And I say, "No, I'm 100 percent Native American. Are you 50 percent American people?" No. Because we're talking about citizenship, not who your parents are. Now who your parents are matters in in nationhood but those are two different ideas that get squashed together and really kind of mess with us.

EmbraceRace: We received a related question from a parent who had adopted a Native child who is not tribally enrolled. She said and wonders what does this mean for how she can support this child in his identity? I don’t have more details than that.

Debbie Reese: Wow. Yeah that's a really dicey one because she should know about the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), first off. Because if she has adopted a Native child, or if anybody adopts a Native child, they should know about this federal legislation that came about in the 1970's because Native children were being removed from their mothers, from their homes, parents were being declared to be unfit to raise their children. And the numbers were astronomical. At the time, we got Native people into Congress and got this legislation passed. A lot of people don't know about it. They adopt a child who, for one reason or another, they think is a Native child. And when you are adopting a Native child, you're in really slippery spaces with this law because the tribal nation has the authority to enter into the conversations about where a child will be placed. So that's been in the news a lot in recent years because we have people in the country who will think, well that child's got blond hair and blue eyes and is only one 1/32 Choctaw. So this doesn't matter. And that's a total misread of what it means to be a citizen of the Choctaw Nation. And it undermines not only that child's well-being as a citizen of that nation removed from that nation, but it undermines the well-being of the nation itself. Because if all your children get taken from you, then you cease to exist as a nation.

So what can she do. First, she better read about ICWA and make sure that she's not on a slippery space because these do end up in court and that's unhappy and unpleasant for everybody involved. If the Native child did go through the ICWA and they are placed with a non-Native family, then I think that a parent should again look for ICWA-related resources [see the National Indian Child Welfare Association] that might be available for that. But if it was, for example, it was a family down the street that had adopted a Pueblo child, I would hope that they would be looking for materials about Pueblo people, that they would go out to New Mexico, where most of the Pubelos are, and spend some time there and do what they can to affirm that child's identity as that, as a citizen or a person of that nation.

EmbraceRace: Thank you for that and let me take you back to your criteria for choosing books, and we have a lot of questions around books in particular. One question was about your point that preferably people would be buying books illustrated by, written by Native writers.

Dr. Debbie Reese: Yes.

EmbraceRace: Now so does this mean are you saying that books about Natives written by non-Natives, you would see that as a flag?

Dr. Debbie Reese: I would. Absolutely. It is actually quite rare that I find a book that is by a non-Native writer that is one that I would say "Here. You can use this one." And I can tell you some that I would recommend right now. Daniel José Older is writing middle grade novels that have Apache characters in them and he's working very hard on it. And those are good. I would recommend those. But those are rare, very rare. It's very rare for me to find those kinds of books.

Discover the AILA's American Indian Youth Literature Award recipients at ailanet.org.

EmbraceRace: Another question: in addition to your site, what trustworthy sources, not only of books but of criteria, maybe of reviews of books about Native Americans might she go to find out to get good recommendations?

Dr. Debbie Reese: One thing she can do that everybody should also do is become familiar with the American Indian Library Association. I'm a member and in the 1990's, we started talking about having an award. And so I worked with other people in the Association and came up with a set of criteria on how we would identify books that we thought merited an award from the American Indian Library Association. So their website, has a page with all the awards [American Indian Youth Literature Awards] and you can read the criteria there on what to look for. I have some pieces of that when I'm reviewing certain books, but definitely that's one place that they should go.

Now we're not monolithic either in how we feel about certain things. Like the American Indian Library Association awarded a book that has a lot of made up dialogue of a person that lived a long time ago, a Native person that lived a long time ago. I think it was Sitting Bull. And I personally and professionally don't like those kinds of books- making up dialogue, thoughts ,emotions and feelings about someone who lived a long time ago. It feels a little bit sketchy to me. I'd rather people not do that.

Another place to go is to Cynthia Leitich Smith. That's another very good resource. She doesn't look just at Native books though. She looks at a lot of books. Her website/blog is Cynsations.

EmbraceRace: Here's another question, from Susan. She says, "I'm a curriculum developer. Beyond identifying realistic and respectful books for children, I'm seeking guidance on story related activities. That is, how to engage children further in a story they've been offered about Native peoples. What activities can deepen children’s experience of the story and remain respectful, inclusive, potentially meaningful and not harmful or cultural appropriating?"

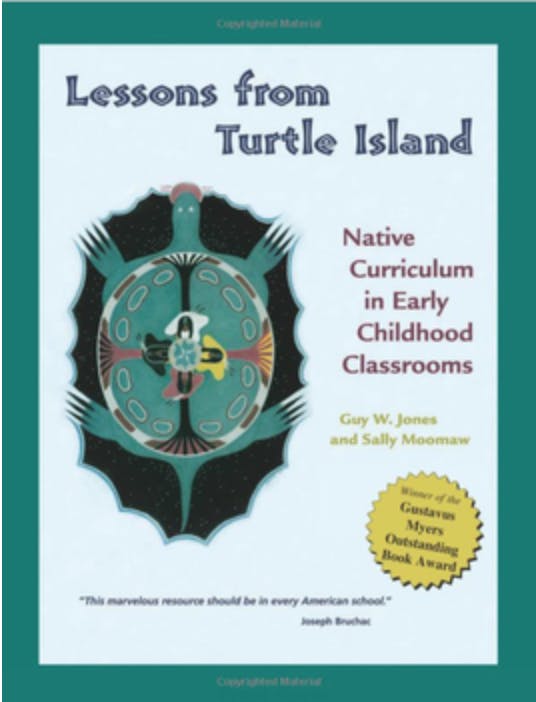

Dr. Debbie Reese: I'm going to see if I can get this book off this pile without knocking the pile down! Yeah. [Holds up book.] This is a great resource for free for people to use - Lessons from Turtle Island - because it does have picture books for early childhood classrooms and activities to go with them. And it has lots of writing from the authors that talk about why you should NOT do X Y and Z, like making totem poles or making dream catchers, [taking what is sacred in particular Native nations and making it a craft project]. Those kinds of activities that are very popular in early childhood classrooms. So this book goes over that a lot. That's a big problem in early childhood classrooms. The idea of "making something" and letting kids, through their tactile interactions with materials, come to know more about people. I don't think that really works. I don't think that really happens. It's just an activity and I think it would be better to spend that time with kids doing something else.

Dr. Debbie Reese: Another kind of activity that I see a lot that is highly problematic is taking what someone thinks is a Native folktale and turning it into a writing exercise. So like How Chipmunk got His Stripes, okay, thinking of a book like that. And reading it and then saying "Now you make a story!" In the classroom, a writing exercise. But these stories are creation stories. They should have the same respect that people give to Genesis. We don't bring Genesis into a classroom in a picture book and then say, "Now you make a story like Genesis!" We understand that it's a sacred story and we don't mess with it. That doesn't happen with Native stories.

When [Native creation stories are] shelved over with the folk and fairy tales, they seem like Little Red Riding Hood. It's not a big deal. It's just a story. It's not just a story! That's a huge double standard that we have that we really need to push back on.

When [Native creation stories are] shelved over with the folk and fairy tales, they seem like Little Red Riding Hood. It's not a big deal. It's just a story. It's not just a story! That's a huge double standard that we have that we really need to push back on.

Dr. Debbie Reese, American Indians in Children's Literature

EmbraceRace: I hope I'm not taking us away, but you're making me think about, I mean I've thought about before and you're making me think more about, Native American as a term period right. The context in which it's useful. So clearly there is something in common, right a relationship that pre-existed the United States as such. The sort of nation to nation relationship with the United States Federal Government. You know there are commonalities as to circumstance, right. Although there's also a wider range of circumstance. But I'm just wondering. You know in what context do you talk about "Native Americans" as opposed to separate nations, particular units? And perhaps a related question that I'm sure you've heard often that we got here is about really what's the right terminology? And I know there's lots of disagreement, but people want to know is it, for you at least, Native America?

Dr. Debbie Reese: I use Native American and American Indian and Indigenous and Native when I'm talking about the larger group of people who are Indigenous to this land. But the best practice always is to be tribally specific. So when people are talking about me, people who are here tonight or who will watch it later, when they sign off and go out into the world and into the classrooms, rather than saying I listened to a lecture, a webinar with Debbie Reese, she's a Native American. I would rather they say with Debbie Reese she's tribally enrolled at Nambe Pueblo because they're gonna say, "What?" And that's an opportunity for that person to share what they learned tonight, that I haven't talked about yet, but that Nambe is one of 19 pueblos in New Mexico. We range the state. We have different languages. We have different ceremonies and different dances and different songs. We're different. And being able to share just that much, I think, would help people understand a whole lot more than they do when they just hear Native American or American Indian.

And each of these terms come out at different moments in history and in another couple of decades maybe we won't be using Indigenous anymore. These things are very fluid. And that doesn't make us less authentic. It's really ridiculous to me that people think, "Well you're not wearing feathers, so you're not a real Indian." [laughs] People change with time and certain activities that any people does or do happens in a certain time and place. People who go to church wear certain clothes when they go to their churches. I wear certain things when I go to certain ceremonies. Just because I'm wearing these clothes here tonight doesn't make me less authentic. It's hard. It's so basic to me but it's so hard to get some of these ideas across.

EmbraceRace: We have a question: “It seems a staggering task to change the way history is taught in our schools where the accepted narrative has erased the stories of nearly all Black, Indigenous, and people of color. There is overwhelmingly systemic resistance to dismantling the canon. Do you think it's possible to accomplish this one teacher at a time?”

Dr. Debbie Reese: I think that's the only way we can do it - is one teacher at a time. Going back to again, what I talked about earlier, these ripples that we can effect change. We have to start with where we are in a moment and hope and encourage people to share that information. It's not going to be easy because the politics of the world right now seem especially difficult to make room for all of us to have good lives being the people that our ancestors were. It's a tough time.

EmbraceRace: Yeah, it really is a tough time.

Dr. Debbie Reese: It is. I want to show you a book that is coming out this July, 2019, An Indigenous People's History of the United States for Young People. I adapted [Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's original book] with one of my colleagues. And it's for young people, and it will be out in June. And hope that teachers will, and people will get a copy of it and use it with kids in classrooms and help them to erase some of the misinformation they have and replace it with more substance.

EmbraceRace: That's fantastic. We look forward to that. There are a lot of questions coming in that Debbie has resources for on her site, so we will be sending you there for those, including book recommendations and more.

Dr. Debbie Reese: I've got them. They're on my Website! The best books tab has best books each year. I try, like the last five years I started doing that.

EmbraceRace: Yeah. We appreciate it. Lots more questions. Can Debbie talk about the concept of curtains in American literature, please?

Dr. Debbie Reese: Yeah. Native people have been exploited by anthropology for over 100 years, and the outcome of that was that across our nations we have become very careful of what we share. And most of the people maybe who are tuned in tonight know about Rudine Sims Bishop and her concept of Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glassdoors. And I was going to do a workshop with some librarians in Alaska, and when I was doing my slides, I thought, well, I'm going to find a window and a mirror that I can use about my Pueblo self and our Pueblo Nation and I want to use that as a visual. And I was looking for that and one of the searches that I did returned one of our ceremonial structures and there was a window, an adobe structure with a window in it, but there was a curtain and I was looking at that and my first thought was that's not going to work. I thought, well there's a curtain there! [laughs] And I just took that curtain for granted. But that curtain is there because we draw the curtains when we don't want people looking in to see what we're doing. That's true of people around the world when we are doing something that we don't want misunderstood, misrepresented, we draw a curtain and we're careful of who we share those things with.

Because our ceremonies were depicted in ways that caused the United States' government to pass policies that said you can not practice your religions, that made it illegal for us to do that, that made it possible for government agents to come in and take our things away, our religious artifacts away. So those curtains are real. They're there to protect knowledge from being exploited and misrepresented. And so I've added, I saw Dr. Bishop recently and I talked with her about this idea that I'm adding curtains to her metaphor. Was that okay? She thought yep, she'd seen that and thought it was fine. So expanding that metaphor to make it work in another way for Native people, for any people really. And the interesting thing about this when I talk about that, a lot of people say, "Well, you're trying to censor. That's not okay. The first amendment. In the United States, we should have access to anything they want to." And all of this rhetoric about this nation comes out and the fact is lots of stuff is kept from the public eye for various reasons.

EmbraceRace: You know that is a really wonderful point that's not often accounted for in how we think about representation. We actually don't have a right to represent, not everything wants to be represented.

Dr. Debbie Reese: Right. You can't even go into the Vatican! You know, you can't just walk into the Vatican and go into any room that you want to. That is a protected space.

EmbraceRace: And as you said earlier, there's clearly some norms around how the Bible can be used and in what context. And those are not questioned for the most part. I wonder, that's a nice segue into questions around cultural appropriation.

Dr. Debbie Reese: Yeah.

EmbraceRace: You began to speak to this and a lot of people are concerned about that. What is the line, right, between respectful engagement and cultural appropriation? You spoke to it a little bit in the context of children and trying to engage children in a range of ways. Can you say a bit more about that if you have any guidance to offer?

Dr. Debbie Reese: It is massive, the appropriation, I mean, is massive and being able to understand something that is that big is hard. I guess the questions that I would ask are: What are you doing? Who is it supposed to represent? And why are you doing it? Kind of a self-reflection on the activity that you might want to do and some honest [laughs] interaction/reflection with yourself about what you're trying to do. Because I really don't think it's, most of the stuff I would say is just not okay.

It's not okay to dress up like an Indian. People want to dress up like pilgrims and Indians at Thanksgiving and the question is, all right so who exactly are you dressing up as? And if you don't know what Nation you would have in this first Thanksgiving reenactment, if you can't name the nation, then you need to stop! Because what you're going to do is reproduce stereotypical construction paper feather bags and headbands and you're just going to use this massive, massive misinformation that you're carrying around to do something that may actually be quite hurtful especially to Native kids in your classroom that you don't know are Native.

It's not okay to dress up like an Indian. People want to dress up like pilgrims and Indians at Thanksgiving and the question is, all right so who exactly are you dressing up as? And if you don't know what Nation you would have in this first Thanksgiving reenactment, if you can't name the nation, then you need to stop! Because what you're going to do is reproduce stereotypical construction paper feather bags and headbands and you're just going to use this massive, massive misinformation that you're carrying around to do something that may actually be quite hurtful especially to Native kids in your classroom that you don't know are Native.

Dr. Debbie Reese, American Indians in Children's Literature

I think that's another piece is a lot of people don't know they have Native kids in their classroom because they don't have dark hair and high cheekbones and so the assumption is they're not Native and there are no Natives in the classroom. Never make that assumption because there may be. That got away from appropriation but I think that again, The Lessons from Turtle Island takes up some of that conversation really well.

EmbraceRace: Yeah. Here’s another question. Do you recommend books by Sherman Alexie?

Dr. Debbie Reese: I do not. I do not. One of my own learnings in the last few years is, it's been a hard one. And so I can talk about it with two books in particular. With his book Thunderboy Jr., when it came out, it was exciting because we had someone who was Native writing for children and experiencing success that no one had had before. That was exciting and it was set in the present day. And I read the book, the first time I read it, and it made me laugh in parts and I thought that it was a book that I would recommend. But then other friends started talking about it, Native friends and gay friends, and I revisited the content of that book and kind of felt myself pulling away from it. And since it came out, I have done some really close analysis of it and studies of Alexie himself and how he has shaped the mainstream expectation of what a Native story should be like and it's just not good. It is pretty bad.

For example, there's a lot of alcoholism in that book and a lot of abuse of alcohol in his young adult diary, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian, and in his speaking engagements and online line, he says: "If a Native person tells you there's no alcoholism in their family, they're lying to you. Every Native family has alcoholism. They are in denial." That's not true. And he says that enough and in enough places that librarians think, okay, if a book does not have someone who is an alcoholic and then it's not an authentic book about Native communities or Native families. That's not true. There are research studies [such as this one and this one] that document that the incidence of alcoholism in Native and non-Native families is the same. It's not different. So a book like that can create an expectation that is actually harmful to other books that don't have that but harmful to Native people too. Because then the expectation is, oh yeah, all of you guys have drunken uncles and alcohol is a major problem. It occurs at the same rate. That's so important to know. And so that's one of that's one piece of his work that is troublesome. There's also writings about sexual harassment and that was a concern for me too. And The American Indian Library Association withdrew the award that they gave to his book because of that. Within Native communities there's a strong community ethic about care for community and that was seen and is seen as a violation of the care for community.

EmbraceRace (Melissa): Thank you for that, Debbie. We have quite a few people asking about how to support their own Native children. Some are very specific but I wonder, I've heard you talk or maybe I've read a bit of you talking about what you did with your daughter when you came across these stereotypes in literature or on TV or in school and I thought it was actually a really helpful response and I wonder if you could talk about that.

EmbraceRace (Andrew): And actually I wonder if we can piggyback on that Debbie because there are another set of questions that I'm sure you've fielded many times, about the “classic books,” right, like Little House on the Prairie, that feature representations of Native peoples that are admittedly problematic. Some people who really think about these sorts of identity and representation issues will say, "You know what, there are lots of good books out there. Don't engage that one. Choose among the good books.” And other folks will say, “No, you can engage any book. They're just better and worse ways of doing it." So with respect to dealing with stereotypes in general and stereotypical and other problematic images in books like Little House on the Prairie, what's your advice on that?

Dr. Debbie Reese: A lot of parents think that they can edit and pause and have conversations with their child with a book like Little House On The Prairie when they come to the bad parts. But as they go through that they keep editing more and more and some parents say: "Forget it. I quit. We wasted all this time on editing this book." So I think what a parent should do is, if they want to use something like that, they should read it themselves first front to back very carefully, very critically. And then give it some thought whether or not they want to go ahead and read that book with their kid and or how they are going to approach their teacher, the child's teacher about that in the classroom.

I really want all parents to raise these questions with teachers because what happens, what happened with our daughters is that we would go in third grade or in fourth grade when Little House On The Prairie was taught at her school, in the neighborhood school. Every time a Native family was in the school, that's when they wouldn't use the book. The Native family moves on, they bring the book back out. That's horrendous. That wasn't learning anything. But if parents did that every year pretty soon teachers are going to really move. I think teachers will really embrace the message that this book is not acceptable for use in a school classroom. I think part of what happens when we try to go ahead and use those “classic books” in a classroom and try to push back on them in the classroom is that the weight of that is on the Native child in the classroom. There may be learning but it's at the cost of the well-being of the Native child. The other children are going to move from this moment, when their teacher is reading this book and talking about its racist characters and qualities, to taking a spelling test or a math test. And the children who are Native, in this case we're talking about Native kids, are carrying this burden, this emotional burden into that test taking situation. That's not fair. That's not fair to them. They should not be asked to carry that burden. That kind of activity does not have to happen in the classroom.

EmbraceRace: We had several questions as well about dual language books.

Dr. Debbie Reese: Yeah!

EmbraceRace: Well, let me ask one in particular. Do you have any children's dual language books in English and any of the Indigenous, First Peoples, or Native languages? If you do, which ones are good to use with the younger, school-aged children?

Dr. Debbie Reese: This book, We are Grateful by Cherokee writer Tracy Sorrell. It's got Cherokee language all through it and it's a year-long look at seasons and activities and events in Cherokee. So that one is one that I would highly recommend. It's nonfiction. And here's Richard Van Camp's picture book. We Sang you Home but it's also in Cree. So I highly recommend this book. And I do have several examples of books like that on my website. Definitely yeah.

EmbraceRace: So if someone is looking for children's books with Native Two-Spirit characters for children in their extended Mashpee Wampanoag family, are there any you recommend?

Dr. Debbie Reese: The only one that I know of or that's coming to mind right now is Awâsis, I wrote a review of that on my website. It's not two-spirit in the way that I think that this family is looking for. What it has is gender neutral pronouns in it. It was wonderful to come across it. There's Native language in that book as well. That’s one I would recommend.

But one of the concerns I have with that idea of two-spirit - I think we're kind of moving into a kind of a pan-Indian kind of … it's not quite stereotype but there's differences across nations and I think it'd be hard for us to really go there with those books until people of those nations are writing those books. And that's not happening in picture books yet that I know.

EmbraceRace: So it's that time. I mean this went very quickly and for us anyway, Debbie, I know it's after all a long day for you and we really appreciate your coming on. Thank you. We thank you so much for coming and sharing all of it with.

Dr. Debbie Reese: I hope it was good.

EmbraceRace: It was great. Yeah. Thank you for engaging. We will bring it forward and we'll all be at our libraries and our schools and I hope everyone learns to use Debbie's site and follow her on Twitter please.

Dr. Debbie Reese: And use Native books all the time, not just in November!

EmbraceRace: Absolutely right. And thanks to all of you who tuned in. Really great conversation in the chat. Thank you!

Related Resources (return to top)

- An Indigenous People's History of the United States for Young People - Adapted from Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's original book by Debbie Reese and Jean Mendoza. Release date June 23, 2019.

- American Indian Youth Literature Awards

- American Indians in Children’s Literature Best Book Awards

- American Indian Library Association

- Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA)

- Lessons from Turtle Island: Native Curriculum in Early Childhood Classrooms

- Rudine Sims Bishop and her concept of Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glassdoors

- Mirrors, Windows, Sliding Glass Doors, and Curtains, from: Writing Native American Characters - Debbie Reese adds curtains to Sims Bishop’s metaphor

- #DiversityJedi Origin Story

- #DiversityJedi on Twitter

- #DiversityJedi write-up in the Kirkus Review

Debbie Reese